(Updated 11/8/21)

UCI Director Tony MacDonald and Rechnitz Family/UCI Endowed Chair in Marine and Environmental Law and Policy Randall Abate arrived in Glasgow, Scotland, on Nov. 2 to participate as official observers at the UN’s COP26 climate change summit. Below we share some of their dispatches from the proceedings. Check back for updates.

In addition, view these media interviews with MacDonald and Abate:

- Q&A: What to expect from latest climate talks, NJ Spotlight News, 11/1/21

- Glasgow climate summit: What NJ expert expects, NJ Spotlight News (NJTV), 10/29/21

ABATE: COP26: The Heat Is on to Secure Meaningful Climate Action

Nov. 3, 2021

Approximately 40,000 diplomats, heads of state, observers, and activists descended on the welcoming city of Glasgow, Scotland (population 635,000), to participate in the much-anticipated 26th Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP26) on Nov. 1-12, 2021. This number of visitors alone would strain Glasgow’s ability to host this major global event, yet approximately 100,000 protesters are expected to arrive on Saturday, Nov. 6, for the “Global Day for Climate Justice,” which should stir things up a bit.

I am happy and proud to represent Monmouth University’s Urban Coast Institute (UCI) at this year’s event as an officially recognized observer organization in the “Blue Zone,” where the diplomats and heads of state negotiate the terms of the agreements that the event yields. My colleague, Tony MacDonald, director of the UCI, joins me in participating in COP26. It is his second COP (he attended COP21 in Paris in the “Green Zone” for civil society participants in 2015), whereas this is my first COP in any capacity.

Like many of its predecessors, COP26 embodies a clash of hope and despair in confronting the global climate crisis. Developed nations boldly convey slogans of hope such as “What Paris promised, Glasgow will deliver,” and “The U.S. is back” (in President Biden’s speech). This optimism is tempered by the realities that marginalized populations face in bearing the disproportionate burdens of the global climate crisis. A leader of a developed country aptly noted at the start of COP26, “The time to act was yesterday.” A chorus of impatient youth climate activists demanding an end to the developed world’s “empty promises” and “blah blah blah” on climate action underscored this sentiment.

COP26 has already delivered at least two reasons for hope in the first few days of the event: (1) the return of U.S. participation and leadership in these negotiations and (2) more active and engaged participation from the private sector in achieving “net zero” carbon goals. President Biden is sending the right messages regarding the return of U.S. leadership. Even if the U.S. doesn’t live up to those bold ambitions, the desire and intention to return to that leadership role is a tremendous boost to global climate governance efforts. Russia and China remain on the sidelines for now, but political pressure will mount for them to participate with the U.S. back in the game. Although it’s a low standard, the U.S. is poised to play a more significant role in climate change diplomacy than it did under the Obama administration, while it seeks to undo the shameful legacy of climate inaction during the Trump and George W. Bush administrations. President Biden has pledged $3.5 billion per year to finance climate mitigation and adaptation efforts in developing countries. This is a step in the right direction, but the U.S. can be much more ambitious than this first step. The response to Hurricane Katrina alone exceeded $9 billion.

The private sector also has been more visible than ever in these climate change deliberations. The responses to the climate change challenges that the world faces will not be attainable without full engagement and buy-in from the private sector. Green hydrogen, offshore wind, methane mitigation, and nuclear power exhibits were prominently featured in the Blue Zone. While there are dangers in the use of science and technology to achieve “quick fix” responses to climate change challenges through the use of certain geoengineering strategies, these clean energy technologies to promote a clean energy transition are essential to ensure that global warming remains below the critical 1.5 Celsius mark.

Stay tuned for the next entry, which will focus on some critical obstacles that threaten to undermine the ambition and inclusiveness of the COP26 deliberations.

On the Scene: Nov. 3-4

MacDonald shared these images from around COP26 on Nov. 3 and 4. Visit his Twitter account (@tmacdUCI) for more inside looks from the summit.

ABATE: COP26: Key Obstacles and Challenges

Nov. 4, 2021

Despite the optimism and hope that COP26 has ushered in, there are many reasons for despair. First, there have been critical logistical shortfalls in COP26 that have hampered global South participation in at least three ways. First, COVID-19 burdens have hit the global South harder than in the global North. As such, the financial and logistical challenges associated with travel to the U.K. during a global pandemic have limited participation from the global South. Worse still, strict COVID-19 protocols have limited room capacity for those able to attend in person in Glasgow. Finally, the COP26 virtual platform has been plagued by technological glitches, further diluting participation from the global South. All of these challenges compound the “climate apartheid” reality of the past three decades (i.e., the global North is primarily responsible for the global climate crisis and the global South bears disproportionate burdens from these impacts).

Second, the goal of climate finance at $100 billion per year also is a hot topic at this year’s negotiations and is essential to the success of COP26. This pledge of support from developed countries to developing countries for climate mitigation and adaptation that was made in 2009 in Copenhagen has not yet been fulfilled. There will be no guarantee that this goal will be fulfilled at COP26. Even if those pledges are made at COP26, pledges are only words until the funds are delivered, which has been problem with some past pledges from developed nations.

Third, although President Biden’s good intentions matter a great deal, they will matter much more when they are backed by concrete actions. A cruel irony surfaced in the U.S. in the week leading up to COP26. The U.S. Supreme Court granted a petition to review the legality of the Clean Power Plan, which is an essential mechanism through which to secure America’s compliance with its emission reduction commitments. Many environmental law scholars see the Supreme Court’s decision to review this challenge as a harbinger of bad news for the Clean Power Plan and the nation’s climate regulation ambitions. Worse still, gridlock in Congress has persisted throughout 2021 on proposed new climate regulation initiatives. With midterm elections looming in 2022, the U.S. may be on very shaky ground to deliver on the commitments it makes in Glasgow.

Finally, in addition to the challenge of mobilizing political will in developed nations on climate regulation ambitions, those laudable intentions often fall short in reality. Many countries have not fulfilled the emission reduction commitments they made at Paris in 2015. Therefore, COP26 is a day of reckoning to get on track toward even more ambitious goals. Based on the current state of compliance with Paris Agreement targets, a UNFCCC Secretariat report from July 2021 found that global greenhouse gas emissions are on track to increase by 16% by 2030, instead of the 45% decrease needed. This dark cloud will hover over the deliberations in Glasgow and propel an unforgiving “no margin of error” mandate to the projected outcomes.

Finally, in addition to the challenge of mobilizing political will in developed nations on climate regulation ambitions, those laudable intentions often fall short in reality. Many countries have not fulfilled the emission reduction commitments they made at Paris in 2015. Therefore, COP26 is a day of reckoning to get on track toward even more ambitious goals. Based on the current state of compliance with Paris Agreement targets, a UNFCCC Secretariat report from July 2021 found that global greenhouse gas emissions are on track to increase by 16% by 2030, instead of the 45% decrease needed. This dark cloud will hover over the deliberations in Glasgow and propel an unforgiving “no margin of error” mandate to the projected outcomes.

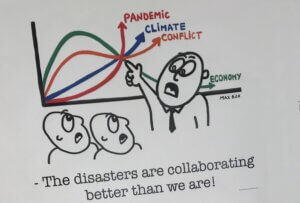

In all other areas of domestic and global environmental governance, humans respond most effectively when there is a palpable emergency. The house has been on fire on our planet for several years now from climate change, yet we still are not embracing the emergency. Although climate change denial has eroded somewhat in recent years because of the palpable climate change-induced disasters around the world, the sense of urgency is still missing. We seem to expect our scientific and technological ingenuity to save us from this crisis as we have overcome other challenges throughout human history. Humanity’s ability to adapt to crises is our greatest strength, yet it is also perhaps our greatest flaw because it prevents us from addressing the root causes of the crises we face.

Stay tuned for the next entry, which will focus on the role of youth climate activism in seeking to raise the ambition of climate action at COP 26.

On the Scene: Nov. 5

On the Scene: Nov. 6

Photos: Global Day of Action for Climate Justice

Randall Abate captured these photos from the Nov. 6 Global Day of Action for Climate Justice demonstration held outside of COP26. Mass mobilizations were organized in cities around the world.

ABATE: Youth Climate Activism May Be Our Last Hope

Nov. 8, 2021

In my youth, I didn’t think about the fate of the planet unless I was reading a science fiction novel. I was enjoying the world around me and soaking up all it had to offer, never imagining how fragile and exhaustible our ability to sustain life on this planet could be. I didn’t have to bear witness to unrelenting life-snuffing disasters as a result of climate change. I perceived nature and the built environment on this planet to be indestructible and infinite.

Times have changed so quickly. Within the span of my lifetime, humanity’s perceptions of the Earth have shifted from an unlimited paradise of resources to support our comfortable lives to requiring emergency life support measures to give ourselves and Earth’s systems a chance to endure what climate change has in store. This abrupt pivot in our relationship to nature affects all of us deeply, regardless of how fully we acknowledge it. But this learned helplessness that we feel as a result of this perilous new normal disproportionately burdens youth. Their carefree childhoods – and potentially the promise of their futures – have been stolen.

Times have changed so quickly. Within the span of my lifetime, humanity’s perceptions of the Earth have shifted from an unlimited paradise of resources to support our comfortable lives to requiring emergency life support measures to give ourselves and Earth’s systems a chance to endure what climate change has in store. This abrupt pivot in our relationship to nature affects all of us deeply, regardless of how fully we acknowledge it. But this learned helplessness that we feel as a result of this perilous new normal disproportionately burdens youth. Their carefree childhoods – and potentially the promise of their futures – have been stolen.

Climate change governance is challenging for many reasons: It is extremely costly, it has been plagued by debates about the reliability of the scientific data, and it requires forward-looking, altruistic behavior, rather than simply responding to clean up a mess. This temporal challenge of climate regulation is even more daunting during a pandemic and a global economic crisis. It is difficult, if not impossible, to overcome the human proclivity to just focus on getting through this month before we focus on what’s in store next year and ten years from now. But climate science demands that we respond with a lens that carefully considers short-term and long-term future scenarios.

Youth climate activism is the check in place in this process to help ensure that a forward-thinking approach to climate governance is sufficiently ambitious. While the enhanced youth engagement is encouraging, it may not be a game-changer in raising the ambition of the outcomes of COP26. Youth voices face many of the same obstacles that indigenous communities and small island nations faced in the COPs from previous decades. Structured processes for their participation are just starting to take hold and are growing quickly. YOUNGO is one example of a youth organization that has a formal advisory role to play in the proceedings, which I witnessed during COP26. But most youth are limited to protests in the streets to convey their concerns and suggestions.

Youth climate litigation in the past decade has been inspiring and impressively impactful in raising the ambition of climate regulation. But lawsuits and protests won’t save the planet in time. The domestic and international levels of governance need to approve and appoint future generations commissions with a charge that is specific to providing advice and consent in climate change legislation and litigation. Such commissions with broader charges to speak on behalf of future generations already exist in several countries around the world. Kim Stanley Robinson’s recent climate fiction novel, The Ministry for the Future, proposes a similar model. Efforts to address climate change simply should not be undertaken without a structured process to reflect youth participation and consent – after all, it’s their future at stake. Indigenous peoples have made progress in the past two decades with the concept of free, prior, and informed consent for projects that may impact their traditional lands. While this mechanism is a start, unless it is considered to represent a veto power on the project, it doesn’t go far enough. Similarly, mere participation of youth advocates in the climate governance process will guarantee that we fall short of what is necessary to protect their futures, and the futures of their children.

Youth climate litigation in the past decade has been inspiring and impressively impactful in raising the ambition of climate regulation. But lawsuits and protests won’t save the planet in time. The domestic and international levels of governance need to approve and appoint future generations commissions with a charge that is specific to providing advice and consent in climate change legislation and litigation. Such commissions with broader charges to speak on behalf of future generations already exist in several countries around the world. Kim Stanley Robinson’s recent climate fiction novel, The Ministry for the Future, proposes a similar model. Efforts to address climate change simply should not be undertaken without a structured process to reflect youth participation and consent – after all, it’s their future at stake. Indigenous peoples have made progress in the past two decades with the concept of free, prior, and informed consent for projects that may impact their traditional lands. While this mechanism is a start, unless it is considered to represent a veto power on the project, it doesn’t go far enough. Similarly, mere participation of youth advocates in the climate governance process will guarantee that we fall short of what is necessary to protect their futures, and the futures of their children.

Youth climate activism is a social movement like many other social movements in the U.S. and the world. Some of these movements secured legal protections and social and cultural legitimacy relatively quickly, such as the LGBTQ+ movement, whereas others continue to struggle to secure the protections they deserve even more than a century after the movement began. For example, the Black Lives Matter movement is a reminder of the long shadow of slavery in the U.S. that perpetuates race discrimination in this country – something that the Civil War, the Thirteenth Amendment, and the Civil Rights movement failed to rectify. Youth climate activism needs a rapid trajectory like the LGBTQ+ movement to gain a foothold in securing the protection of their interests because there is very little time remaining to get this right.

In many ways, COP26 will likely be remembered as the beginning of a new era of holding governments accountable to youth expectations in climate governance decisions. The Rio Convention in 1992 marked the beginning of these global youth concerns with the rollout of three new major international environmental agreements, including the UN climate change treaty. I was moved by a 2020 short film, “Only a Child,” which I viewed at COP26. The film is based on a speech delivered by a 12-year-old girl at the Rio Convention. It compellingly portrays youth concerns at that time of what was at stake in the need for effective global environmental action. Unfortunately, those concerns have gone largely unaddressed. A quarter-century of empty promises on climate change governance has caused youth concerns to reach a boiling point.

Youth accountability efforts will continue to take the form of climate protests and climate litigation in the near term. But to the extent that politicians continue to fail to regulate climate change for the emergency that it is, youth climate activism may have no choice but to move beyond “tokenistic” objections with little to no impact, and resort to more confrontational methods of engagement, ranging from strategic direct action against the fossil fuel industry to organizing an Eco-Marxist revolution in climate governance.

Time is short and her future is on the line.