Cross-posted at PolitickerNJ

Now the work begins. With the appointment of Alan Rosenthal as the 11th member of the New Jersey Apportionment Commission, the work on drawing up a new legislative map commences in earnest.

A number of interested parties have already weighed in at public hearings, asking for a map that would bolster their group’s representation in the legislature. However, I have yet to see draft maps that cover two particular takes on the redistricting process – the constitutional guideline approach and the competitive election approach.

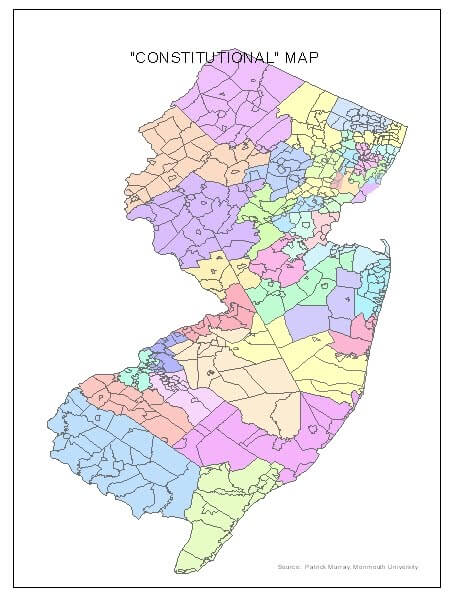

This column examines one possible “constitutional” map. (I’ll tackle a competitive map in a few days.) There are many ways to define a constitutional map. For my purposes, I looked at a few key provisions.

First and foremost are the federal guidelines for legislative districts: equal population (with no more than a 10% variance between the largest and smallest district), contiguous, and compact. The map must also conform to certain provisions of the Voting Rights Act.

First and foremost are the federal guidelines for legislative districts: equal population (with no more than a 10% variance between the largest and smallest district), contiguous, and compact. The map must also conform to certain provisions of the Voting Rights Act.

The New Jersey Constitution also provides guidelines. Legislative districts must be “as nearly compact and equal in the number of their inhabitants as possible,” and “no county or municipality shall be divided among a number of Assembly districts larger than one plus the whole number obtained by dividing the number of inhabitants in the county or municipality by one-fortieth of the total number of inhabitants of the State.”

In other words, to determine the maximum number of districts that a town or county should have, divide the town or county’s population by 219,797 (one-fortieth of 8,791,894) and round up. For example, Bergen County’s population of 905,116 yields five allowable districts (i.e. 4.1 rounded up to 5).

The municipal/county split provision can be disregarded if it is necessary to meet other federal and state constitutional mandates (i.e. population equality, contiguity, compactness). However, the legislative map drawn up in 2001 appears to have violated this provision more than was statistically necessary. In addition to splitting Newark and Jersey into three districts, 15 of 21 counties have more district “splits” than the formula allows.

My objective in drawing this map was simply to see whether it is possible to draw a map that strictly adheres to the state constitution. Bottom line: it’s not possible. But you can come close. I was able to reduce the number of counties with over-splits to seven – and only one of those counties included more than one “extra” district (for a total of 8 county over-splits, compared to 24 in the current map).

I purposely drew this map totally blind to a number of other important concerns that the commission may take into account, such as include minority group representation, current party control of districts, partisan voting patterns, and incumbent hometowns. That doesn’t mean I am unaware of the consequences that such a map would bring. I’ll discuss those below, but first the map itself.

This so-called constitutional map meets standards of contiguity and is relatively compact. [Note: The map is not the most compact possible, but “compactness” has been very broadly defined by the courts.] It also meets guidelines for population equality. The largest district, LD15, has 231,723 people, while the smallest, LD12, has 210,245. The difference between the two (21,478) is just under the 10% federal limit – 9.8%, to be exact.

Reducing the number of districts in Newark and Jersey City from three to two was easier in the former city than the latter. Because of the size and layout of the Hudson County municipalities, the existing majority-minority district shifted from 33 to 32. However, this change is somewhat semantic, since the West New York and Guttenberg moved from 33 to 32 as well.

The need to keep small (i.e. below 220,000 population) counties whole shifted some Cumberland County towns into LD3 and put more of Atlantic County in LD1. This necessitated some wholesale municipality shifts in LD4 through LD7. Similarly, Hunterdon and Warren counties needed to be placed into different districts to preserve their county boundaries.

Because of their shrinking population share, the Bergen/Essex/Passaic districts were basically redrawn, with one district disappearing entirely. That district, LD34, reappears in southern Somerset County. The middle of the state also saw a total makeover of LD14.

Now, on to the consequences. What would this new map do in terms of minority representation? Answer: probably not much. (See my prior column for a discussion of this issue.)

There would still be one Hispanic majority district. The number of districts with a 40% to 49% Hispanic population would increase from three to five, while the number with between 30% and 39% would decrease from three to one. A total of 12 districts – as compared to the current 13 – would have a Hispanic population of 20% or greater.

There would also continue to be one Black majority district, but the number of districts with a 30% to 49% Black population would decrease from five to one. However, a total of 13 districts – as compared to the current 12 – would have a Black population of 20% or greater.

Also, the number of districts with an Asian population over 20% would remain stable at five.

Next question: What would this new map do in terms of partisan control of the legislature? Answer: probably not much, but it would make for some interesting match-ups this June and November.

Based on voting patterns over the past few election cycles, 23 districts in the current map are in the Democratic domain and 16 are Republican. The remaining one, LD14, has been a split district for most of the past decade and has seen a number of close elections. Looking at the current map another way, 26 districts are “sure-fire” partisan – defined as an average victory margin of 10,000 votes or more for one party or the other. Another 13 are strongly partisan, with average victory margins of 3,000+ votes for a single party.

The new map doesn’t change that much: 23 districts are slam-dunks for one party and 12 are strong likelihoods. The remaining five districts lean toward one party by at least a 1,000 vote margin on average (four Democratic and one Republican). The bottom line gives us 23 Democrat trending districts and 17 Republican ones.

The real fireworks come in the incumbent face-offs that would be a byproduct of this map. Keep in mind that I was purposely blind to who lived where when I drew the map.

There are some Senate match-ups that will ensure this map is nixed by both parties. On the Democratic side, Senate President Steve Sweeney and Donald Norcross both land in LD5 and Nick Scutari and Ray Lesniak share LD20. On the Republican side, we have Joe Kyrillos and Jen Beck in LD13 and Tony Bucco and Joe Pennacchio in LD26.

Cross-party incumbent face-offs are led by Minority Leader Tom Kean and Bob Smith in LD22, where the Republican would have a slight advantage based on recent voting patterns. GOP stalwart Gerald Cardinale squares off with Bob Gordon in LD39, which leans to the Democratic side. The most interesting race would involve a primary between Nia Gill and former Governor/Senate President Dick Codey in LD27, with the winner likely defeating Kevin O’Toole in the general election.

On the Assembly side, Rible, Angelini, and O’Scanlon would fight it out for the two GOP spots in LD11 and Schroeder, Russo, and Vandervalk would do the same in LD40. Three Democrats, Johnson, Vaineri-Huttle, and Voss would draw straws in LD37.

A GOP leaning LD22 would pit Democrats Green and Stender against Republican Braminck, LD21 teams Majority Leader Cryan and Jasey in a likely win over Munoz, and LD4 includes Democrats Moriarty and Burzichelli along with Republican DeCicco, who will likely take on Fred madden in the Senate contest. LD30, which leans slightly Democratic but could be a toss-up, has three Democrats – Conaway, Benson, and DeAngelo and one Republican – Malone. Somerset County Assembly members Chivukula (D) and Coyle (R) are the sole legislative incumbents in the new LD34 and could face each other for the Senate seat in what is likely to be a Republican victory.

This map appears to meet all the basic federal and state Constitutional criteria for drawing legislative districts. However, I’m not necessarily advocating for its adoption. It may not be the best map for the state – in fact, it probably isn’t. But it does show what happens if you try to stick to certain rules over other considerations.

Next up – my take on a more competitive map.