A memorial celebration honoring the late Kenneth R. Stunkel, emeritus professor of history at Monmouth University, will be held in Wilson Hall on Monday, April 8, from 3–5 p.m.

Stunkel passed away on Feb. 7 at the age of 87. Throughout his distinguished 47-year career at Monmouth, he served as dean of Humanities and Social Sciences from 1996–2001 and dean of Art and Sciences from 1993–1996. Stunkel taught over 25 different courses and authored 10 academic books, including “Ideas and Art in Asian Civilizations, Understanding Lewis Mumford: A Guide for the Perplexed,” and “50 Key Works of History and Historiography.” After his retirement, Stunkel and Robert Rechnitz, a friend and colleague, coauthored a play called “Lives of Reason.” The play was produced in 2016 at Two River Theater in Red Bank, New Jersey and enjoyed sold-out performances. Last year, Stunkel’s second play, “How to Live,” was given a staged reading at Two River.

Stunkel, who was instrumental in Monmouth College’s transition to University status, left a lasting impact on our community. Saliba Sarsar, Ph.D., professor of political science and sociology, Rekha Datta, Ph.D., Freed Endowed Chair and professor of political science, and Vincent DiMattio, M.F.A., professor of art and design, shared tributes in honor of his legacy.

“A Warm Tribute to Kenneth R. Stunkel” by Professor Saliba Sarsar ’78

The loss of a loved one is never easy. What partially fills the void are the rich memories—the passionate embrace, the special moments, the selfless acts in support of those near and far.

The passing of Kenneth R. Stunkel—my dear friend, colleague, mentor, co-author, and confidant—is tough but his generosity of spirit, unparalleled knowledge, wisdom, and wit will persist to warm the heart, to inspire the mind, to motivate action.

Ken, as he liked to be called, was a pillar of Monmouth University. His support of the community, his interest in the progress of his colleagues and students, his administrative acumen, his stimulating conversations—all spoke of the qualities of a servant leader, an engaged mind, and a caring soul.

I first met Ken as a student in history and political science at Monmouth but got to know him well when I joined the faculty and academic administration. He took me under his wings, soon calling me “my son,” to which I always responded with affection, “my dad.” When I got married he and Mary Carol were most kind to hold a lovely wedding reception for my wife Hiyam and I (both of us were born and raised in Jerusalem, with no family in New Jersey).

Ken and I crossed paths on a regular basis as we served on countless committees and built a couple of institutes, along with several colleagues, and as I served as his associate dean in both the School of Arts and Sciences and the School of Humanities and Social Sciences. We co-authored two books, one on world politics and the other on ideology, technology, and values in political life, as well as several essays. We were proud of each other’s accomplishments.

Ken, as those who knew him will tell you, was a “Renaissance man.” He loved and was conversant in art, architecture, literature, philosophy, dance, music, opera, and theatre, just to name a few. He travelled extensively in Asia and Europe and integrated much of what he learned into his courses through the use of photos he took on his travels and slides he purchased at archeological sites and museums. He was a prolific writer, authoring important books, scholarly articles, book reviews, essays, and conference papers.

Above all, Ken was the public intellectual par excellence, always passionate and concerned about the future, our collective future. In a long email he sent me some four years ago, which I believe he wouldn’t mind me sharing with others, he expressed great concern for the fate of our planet and the incapacity or reluctance of citizens and governments to think and act past tomorrow.

Atmospheric carbon is over 400 ppm, up from 300 two hundred years ago. The ozone hole is wider. Ocean acidification is 35 percent greater. Rain forests are disappearing beneath ax and plow. Antarctic ice is melting faster than anyone believed likely because of warmer waters. Sea levels are rising. Global temperatures are pushing a two degree increase. Thousands of species, plants and animals, are recently extinct or pushing extinction every year. Fresh water supplies are being destroyed everywhere…. Population continues to threaten itself with exponential increases, up to seven billion now from less than three billion in 1970, with eight billion coming up very soon. The children keep coming without much thought by parents about the kind of world they’ll have to live in. None of this can be reversed. Meantime, nations and peoples go on behaving much the same way. Economic growth is the global mantra. The battle is on for fossil fuels and other resources. Carbon emissions could slow but they won’t stop. The habits and forces that produced all the trouble are securely intact. Not only is it too late, the situation is sure to get worse down the line until folks have their backs to the wall. Then will we have “global understanding?” Will worse conditions be headed off? I doubt it….

In a successive article titled, “Ecology and Economy: America Unraveling,” he explained,

A change of heart and reform from the public and those in authority is moot, as it has been for the past [40] years. No one can win and hold public office in America with a message of limits, which would mean an economy guided by ecological principles…. Personal, political, and corporate interests find all the excuses needed, including flat denial that anything is amiss…. Of course, the world is not going to come to an end, but the philosopher G. W. F. Hegel said the owl of Minerva (wisdom) takes flight only when the shades of darkness (disaster) have fallen. So it is likely to be with our improvident species.

It behooves all of us to listen carefully to and reflect on Ken’s views. Let not philosophic wisdom come too late. Let us not look back on the disasters and follies we have created and only then understand what needed to be done. We have a choice.

Ken lives on … His voice resonates and his touch is felt through the halls of Monmouth and beyond. He is now free to sing, to dance, and to celebrate a life well lived. As Gibran Khalil Gibran, the Lebanese-American poet, writer, and visual artist, and one of my most favorite creative thinkers, wrote,

Only when you drink from the river of silence shall you indeed sing.

And when you have reached the mountain top, then you shall begin to climb.

And when the earth shall claim your limbs, then shall you truly dance.

“The Renaissance Man” by Professor Rekha Datta

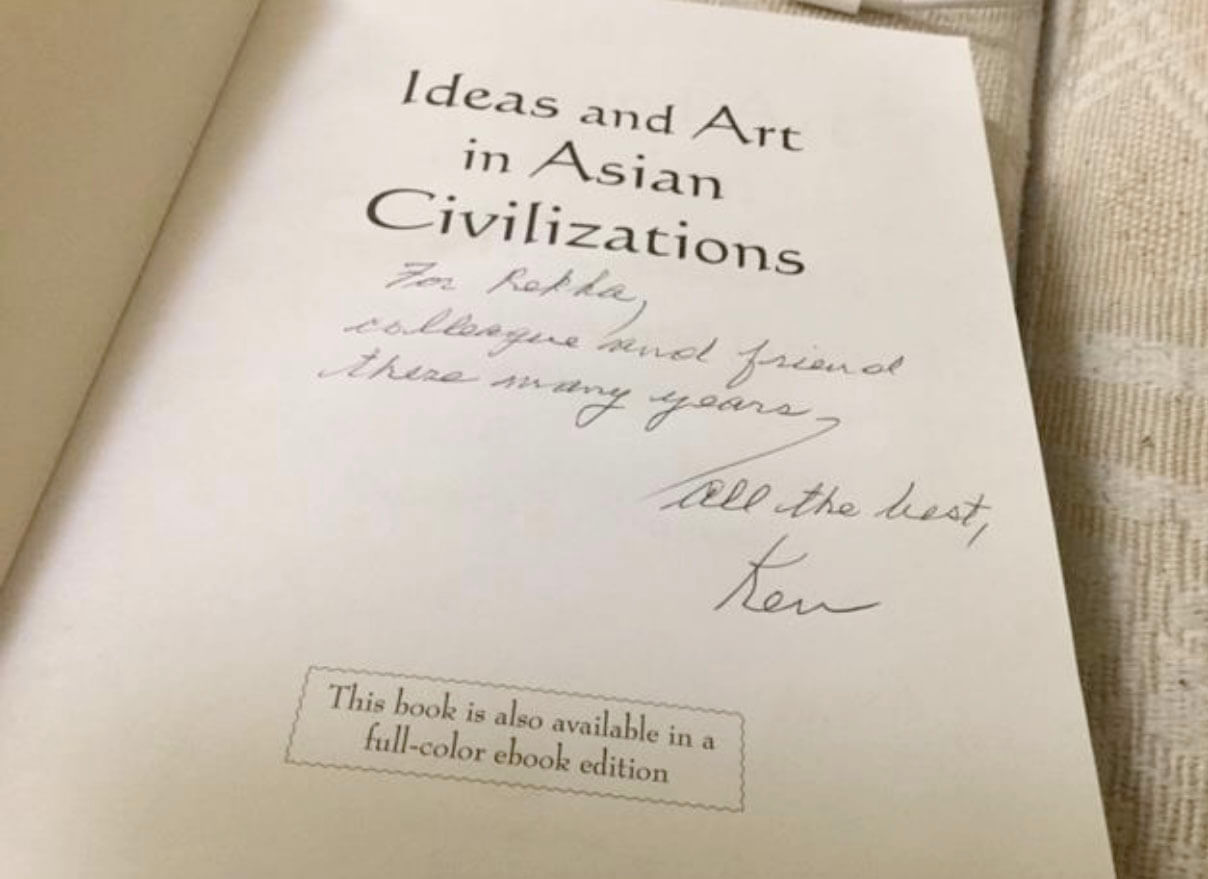

On Feb. 7, it felt like “knowledge” died. With the passing of our dear colleague and friend, Ken Stunkel, a lot of wisdom and precious intellectual wealth left this world. Ken was a towering figure at the University and the wider community with his multifaceted knowledge. I used to call him “the Renaissance man.” There can and will be volumes written about Ken’s intellectual contributions beyond his 10 books and numerous articles and reflective pieces. I will always remember how he helped me find a place in the campus community, how, as he inscribed in his 2012 book, he considered me his “friend and colleague, these many years.” In my humble existence, to have Ken consider me a colleague is an honor. To have him call me a friend, a blessing.

When I joined Monmouth University in 1994, it was still a college, and Ken was the dean of Arts and Sciences. He was my dean. When I joined the University, as a South Asian immigrant woman of color, I was somewhat of a rare species on campus. In an environment where I had to field questions like, “How does it feel to be different?,” Ken, along with some other senior colleagues, helped me so I did not feel different. He was a beacon of tolerance and cultural understanding. With his vast knowledge of Asian and world culture, history, science, architecture, and so much more, he always made me feel disarmingly at home and at ease. Actually, it was unease, because his knowledge about Asia and India was so much deeper than mine. He had deep knowledge of Indian classics, dance, and we would often engage in long conversations on the legendary Uday Shankar, and the nuances of Sanskrit, Vedas, Moghuls, British, and even modern Indian history and contemporary politics. Fortunately I had Sanskrit as my third language in school. And fortunately I am an avid admirer of Rabindranath Tagore and his works, which Ken knew inside out.

I was fortunate to share the stage at two off-campus conferences where Ken spoke about Tagore, the first Asian and the first non-European to receive a Nobel Prize in Literature. Ken knew of my love for Tagore, whose writings I enjoy in my mother tongue of Bengali. Ken and I would talk about the Gitanjali, or “An Offering in Songs,” for which the poet had received the Nobel, and Tagore’s other works in English which he had consumed voraciously. When he had his office in Bey Hall, a few doors from mine, Ken and I would have extensive discussions about another famous Bengali, the philosopher-economist, Amartya Sen, who had won the Nobel prize in 1998. Such discussions took me home, helped me bridge the gap between “Home and the World,” a novel made into a film by the Oscar-winning Indian film maker, Satyajit Ray, about whom Ken knew volumes too.

There is a Sanskrit phrase, “Vidya dadati Vinayam.” Knowledge brings humility. New to the campus as a temporary visiting instructor, I often felt invisible and intimidated at college parties, receptions, and meetings. Most of all, I did not expect the dean to even notice my presence. But Ken always found a way to include and engage me in conversations and reflections about politics, culture, and history. He made intellectual and physical space for me as a colleague, as a friend. I felt humbled at his presence; grateful that he spent time discussing philosophy, politics, and literature with me.

There is so much to write, so much to reflect on this Renaissance man. Even my husband Subrata came to appreciate the nuances of higher education professionals and campus politics packaged with humor when we watched “Reasoned Lives” at Two River Theater. This was a play that Ken wrote with his friend Robert Rechniz, after he retired from active teaching, which he did at Monmouth for 47 years! The creative and master mind was always at work, even after retirement. I recall Ken had invited a few colleagues at his home several years ago to mark a celebration. I was fortunate to visit his beautiful home and meet his wife, Mary Carol. One of our colleagues pointed to the piano and a desk by the window overlooking the green scenery outside and asked if that was where the great compositions came from. If I remember correctly, he immediately obliged us with a beautiful selection from Chopin.

In 2014, in an email Ken challenged us to think about “global understanding” in a comprehensive way. “Everyone’s fate is gripped by a world changing under our feet faster than anyone expected or predicted even [10] years ago. When Kristof was here, he said the greatest moral issue for humanity is the status of women. I disagree. The greatest moral issue is a handful of countries (the [U.S.], China, the European Union, etc.) living in a way that is wrecking the ecology of the planet….. They expect their “way of life” (nonstop consumption and freedom to do pretty much what they please) to go on until the “American dream” (all the good things of life) is safely in hand. I think one of your future conferences should devote itself exclusively to these matters.” If we ever have a global conference on campus again, we will remember that and you, Ken.

In 2015, while directing the Center for Teaching and Learning (CETL), I led a discussion series on the value of liberal arts and general education. Ken shared his vision with me. “…Departmental interests must bow to the ideal of liberal study in general education. At the general education level, specialization can be fatal. Teaching faculty must spread their intellectual wings, put a lot of stuff together, be daring and adventurous, and talk a language outside the major and professional journal. Finally, the credit load for general education can be modest. What counts is the quality of teaching by faculty who understand liberal studies.” In fact, this is a lesson I learned from Ken and some other senior Monmouth mentors and colleagues years ago, in my decade-long tenure as department chair, and in leading efforts to nurture interdisciplinary global and cultural understanding on campus.

My good colleague Saliba Sarsar and I are currently co-editing a book “Democracy in Crisis.” At Saliba’s request, Ken had agreed to write the chapter on East Asia, which he told Saliba, would probably be his last publication. Alas, it wasn’t; it wasn’t to be, and that fills me with sadness. Just last week, Saliba and I were discussing if we should reach out to Ken and talk to him about his chapter. But I also reckon that after a lifetime of numerous and multifaceted contributions to the worlds and words of dance, art, culture, literature, history, and so much more, the Renaissance man must rest.

Ken would often begin his emails or in person greetings with these words: “I hope you are flourishing.” Often that would unleash a discussion of Aristotle and if we were anywhere near attaining the good life that he had envisioned. In his final e-mail to me, Ken wrote, “Keep those Tagore songs rolling.” So, here is some Tagore for you, Ken: “You stand beyond the threshold of life and death, my friend. The sky is silent, my arms extend toward you, your seat in my lonesome heart fills with light.” Rest in peace, my dean, friend, colleague, and intellectual guru. Thank you for showing me how to spread my “intellectual wings.”

Tribute by Professor Vincent DiMattio

For those of you who did not have the distinct privilege of knowing Ken Stunkel, please know that he was a giant of a man. He was my mentor and my best man and his valuable and caring advice aided me through the many years of our friendship.

This man of all seasons was passionate about the state of our planet confirming his absolute trust in science. His profound love of classical music, and the magic of the written word as evidenced by his impressive, well-rounded library were an important part of his life. Our University has produced its share of scholars and Ken was at the very top of that list. His many contributions as dean of Humanities and Social Sciences for 13 years are well documented in his personal dossier. Much like Greek scholars, his love of life was not just intellectual but also physical because of his passion for dance, and as a gymnast performing the almost impossible still rings event. All of my memories of Ken are positive ones. He was a pleasure to be around and to share his love of life and his wonderful sense of humor. This was a man who was larger than life. We are taught that we are all expendable but Ken could give us a convincing argument that he cannot be replaced. Until we meet again my friend, the love and memories will persist.