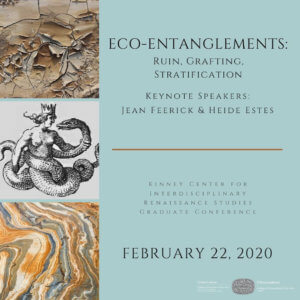

English Professor Heide Estes, Ph.D., gave a keynote lecture at the conference “Eco-Entanglements: Ruin, Grafting, Stratification” at the Arthur Kinney Renaissance Center of the University of Massachusetts on Feb. 22.

English Professor Heide Estes, Ph.D., gave a keynote lecture at the conference “Eco-Entanglements: Ruin, Grafting, Stratification” at the Arthur Kinney Renaissance Center of the University of Massachusetts on Feb. 22.

In her remarks on “Gender, Disability, and Environment in Old English Poetry,” Estes discussed the Old English poem Juliana, which chronicles the life of the fourth-century saint martyred in the Greek city of Nicomedia, an area now part of Turkey. Juliana was tortured and then killed by the Nicomedian Prefect, Eleusis, after she refused to participate in the marriage that he had negotiated with her father.

Ideas about gender, disability, and the environment interact in complex ways in the poem, Estes says. She explains that thinking about these issues with respect to literature written 1000 years ago is not just an intellectual exercise, but relevant to how we think today about human interactions with the environment, as well as how different groups of humans are characterized in problematic terms.

In the lecture, Estes addressed how theorists of contemporary as well as medieval society point out that disability is to a large extent socially constructed, in that a particular physical impairment or infirmity may or may not be disabling depending on a society’s architectural and cultural organization. Leprosy, for example, does not limit the activities of afflicted people, but its visible signs led medieval people to describe it as disabling. Nearsightedness might be a positive development in a scribe, but problematic for a sailor; in contemporary North America, eye-glasses can be fashion statements while canes and hearing aids often bear stigma.

Estes further explained how feminist theorists have pointed out that women’s bodies are seen as non-normative. In the middle ages, menstruation and childbirth were characterized as “illness.” Women were until recently excluded from full participation in economic, legal, and social life, and remain excluded from certain religious activities, and have thus been socially disabled based upon assumptions about competence made based on physical difference.

While some environmental theorists take “man” and “nature” as two distinct and undifferentiated categories, Estes pointed out that there is no word in Old English meaning “nature,” and different natural environments like wilderness, farmland, village, and sea have different literal and emotional senses. Moreover, humans of separate categories interact very differently in early medieval texts as well as more recently with the environment, depending on their social power and physical embodiment. Estes concludes that class, gender, dis/ability, and race can all impact the freedoms that people have in moving through wilderness and urban environments alike.

In Juliana, the prefect Eleusis is depicted as blind with rage and likened to a wild animal in his intemperate reaction to Juliana’s refusal of marriage. She, meanwhile, is unharmed when he has her hanged by the hair from a gallows and then attempts to burn her with flames and melted lead, though the fire explodes and the lead burns Eleusis’ men instead. At the end of the poem, Eleusis goes on a sea journey and his ship is destroyed by waves, and he and his men killed. Meanwhile, Juliana’s Christian faith makes her impervious to harm from natural forces. Eleusis is characterized in terms of disability and animal wildness in the limits on his power over Juliana. Her powerlessness as a woman becomes irrelevant because of her adherence to faith, and environmental forces become unable to harm her even as they destroy Eleusis. Constructions of environment, disability, and gender interact in the poem to create shifting hierarchies in a depiction of the competing claims of political power and Christian faith.