Waves of Creativity

Associate Professor Kimberly Callas’ latest project merges art and science to highlight our oceans’ hidden depths and ecological significance.

Kimberly Callas stood aboard the R/V Seahawk studying the deep water that swayed all around her. As hard as she tried, she couldn’t tell what glided, lurked, or swam below the surface. There was just opaque ocean in every direction, broken only by the horizon line.

“I saw nothing,” she remembers, “and that was so interesting to me.”

But how could she translate this formless sea into art? That was, after all, the point of her voyage. Callas, an associate professor of art and design, had joined several scientists from Monmouth’s Urban Coast Institute (UCI) for a tour of their local research sites in late 2019. She was spending two years as artist-in-residence at UCI—an M.F.A. working beside Ph.D.s; an artist blending facts with feelings.

“There was so much underneath me, yet I had no concept of what it was,” Callas says of her outing on the UCI vessel. She later turned that into a 10-foot-tall mixed-media work, “Whale Boat,” which places a giant whale below a small—and likely oblivious—boat at sea.

“Whale Boat” is part of her larger “Ocean Bodies” series, which Callas has been working on for the past five years. Inspired by her time as a faculty fellow at UCI, “Ocean Bodies” now includes more than 40 pieces, with images and symbols of water and whales, boats and nets, the horizon line and the human body. Many of these works highlight nature’s beauty and its cosmic origins while also hinting at the threats and destruction it faces.

“I think we all have this deep connection to nature, and we’ve forgotten it,” Callas says. But she’s well aware. That’s why she writes about it, teaches about it, and makes art about it—including a solid month focusing on her “Ocean Bodies” series earlier this year.

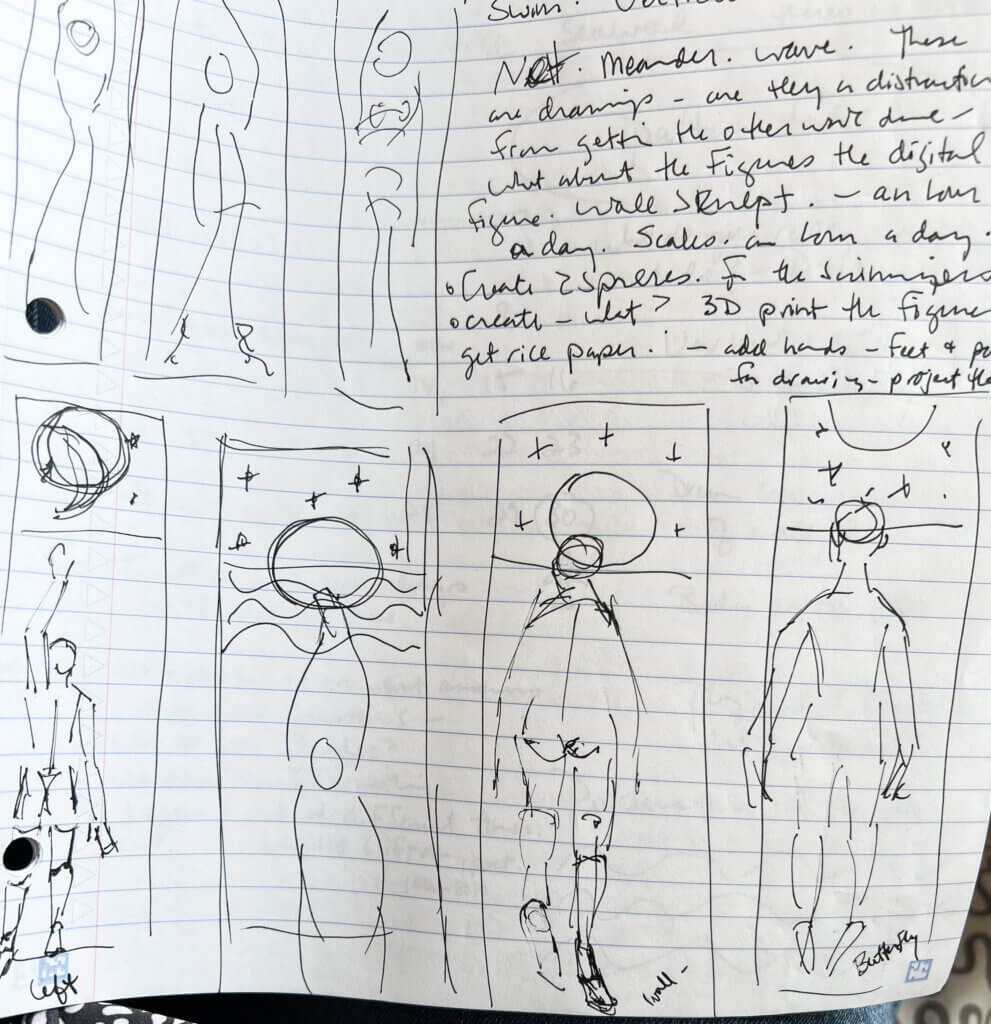

Callas spent all of March in Hungary as an artist in residence at the Art Quarter Budapest (AQB), an independent art center. Living and working alongside five other international artists, she’d read and write each morning, then head into the studio for a full day of sketching, drawing, and digital sculpting. She met local artists and visited museums. At night, the artists in residence sat together discussing their day’s work and swapping visions, perspectives, and techniques.

Going into her residency, Callas had planned to work on life-size human sculptures for her “Ocean Bodies” series, and she did that. But she also found herself fixated on four tiny sketches she’d made of people swimming. “I was trying to be open to other ideas, but I kept coming back to the swimmers,” she says.

In a resulting show at AQB, “Ocean Swimmers (Entanglement),” Callas exhibited a quartet of four-foot-tall black-and-white drawings of her swimmers. Their bodies are each in different positions, but all are posed vertically, reaching out of the water and up toward the moon. She captured the whirling, blurry motion of ocean waves by using water-soluble graphite pencils on paper. It’s a tricky medium to control, she says, but that’s the point—no one can control the ocean, either.

These new swimmers join her “Ocean Bodies” series in trying to raise awareness of the ocean’s role in climate regulation and stability. She says the “entanglement” in their title refers to both humans’ entanglement with the natural world and also the species-threatening entanglements that North Atlantic right whales face from ropes and ships at sea. (Right whales, which migrate through Jersey Shore waters, are seen throughout “Ocean Bodies,” including in “Whale Boat” and “Night Whale Entanglement.”)

When it comes to addressing big environmental issues, “everybody needs to find their narrative,” says Tony MacDonald, director of Monmouth’s UCI.

“Sometimes scientists and lawyers think they can convince people of things by giving them facts,” continues MacDonald, who is a lawyer himself. “But an even more powerful way to galvanize action is to get people emotionally involved. Kimberly’s work really reflects that.”

Weaving ecological science into her art isn’t new for Callas, nor is her deep concern for the climate crisis. In fact, during this interview, she’s speaking from the sod-roofed, solar-powered, wood-heated stone house that she and her husband, George, built by hand in Brooks, Maine.

That was her first eco-focused project. Neither of them knew how tough it would turn out to be, but building an off-the-grid home stone by stone appealed to both the environmentalist and artist in her. “It just sounded very sculptural and like something I could do,” she says.

Callas grew up in rural Northern Michigan, in a small town sandwiched between state and national forests. She spent most of her time playing outside, building houses out of sticks and collecting red wintergreen berries. “Those were my favorite toys,” she says.

Eager for a bigger pond, she studied sculpture at the University of Michigan, then moved to New York City to pursue her MFA in sculpture at the New York Academy of Art. She was walking to her studio, where she’d been focusing on sculpting human figures, when she saw a plane smash into the World Trade Center on 9/11. She was five months pregnant, and George had left the building only a few minutes earlier.

“My husband and I were already environmentally minded,” she says. “We were weighing our garbage, we were vegetarian. But after 9/11, we said, we really have to do something different.”

Enter the eco house, which they built together from 2003 to 2006. “At that point, I didn’t know if I was going to make art again,” she says. “I thought the environmental crisis is the issue, and it felt like me sitting in my studio does nothing for that.”

With the house complete, she and George cofounded with another couple a nonprofit institute, Newforest, which focused on sustainability research and education. That’s where she first began collaborating with scientists. “Our board had poets and economists and scientists, artists and engineers,” she says. “The idea was that we’re too siloed and can’t deal with these environmental issues that way.”

Leading creativity workshops at Newforest brought Callas back to an artsy state of mind, and soon she was back in her studio. But her work was different now. It was focused squarely on nature.

Even after Newforest closed in 2010, Callas continued her work at the intersection of art and sustainability, joining projects at Unity College and the Mount Desert Island Biological Laboratory in Maine. She’s keenly aware of the overlaps between her and her scientist collaborators. “Scientists go out in the field, and artists do, too,” she says. “We’re all looking so closely; it’s all about observation. We all have tools we use, and a language and a process. It’s fascinating when we bring all of those together.”

But her collaborations extend well beyond scientists. When Callas came to Monmouth in 2016, she brought along one of her longest-running endeavors: Discovering the Ecological Self. The project took root during her years at Newforest and continues now as workshops, residencies, courses at Monmouth, and in Callas’ own art. “All of my work falls under the Ecological Self,” she says.

While working in sustainability, she realized that personal connection, not scientific data, was most likely to sway people’s outlooks and behavior. The Eco Self project centers on “finding out where that deep passion for nature is in you,” Callas says. Maybe there’s a specific tree that defined your childhood. Maybe you keep seeing crows everywhere, or a certain flower continues to pop up in your dreams. Whatever your connection to nature, Callas wants to help you discover it, explore it, and make art about it.

She weaves the Eco Self into her courses at Monmouth, including Eco Art (AR 231) and Sculpture II (AR 218), and she’s brought it to museums, libraries, nonprofits, and universities near and far. “We need to reawaken this ecological self,” Callas says. “It’s there. There’s no way we can be separated. But our life is designed in so many ways to have us think that we are separate. And that’s how we don’t see the destruction.”

As a result of her Eco Self programs, “I want people to become environmental activists. I want them to become social-practice artists,” she says. “I’ve had people leave the art school and go into environmental science after taking that course.”

Megan Delaney, an associate professor at Monmouth who focuses on ecotherapy and ecopsychology, published a paper about Callas’ Eco Self work—specifically, a workshop collaboration between her Sculpture II class and the nearby Aslan Youth Ministry. For multiple weeks, Callas’ students guided the children from Aslan through the Discovering the Eco Self process and into creating their own social-practice art pieces.

“I think we tend to take care of things that we have a connection to and feel rooted in,” Delaney says. “If we’re going to take care of our place in space, we have to feel connected to it, and Kimberly does that through her Eco Self project in creative ways.”

I’m interested in exploring our emotional attachments to nature and the process of how we create meaning out of the natural world.

She notes that Callas’ own art offers further ways in. “When we see beautiful paintings of nature, we feel connected to saving it or valuing its importance,” Delaney says. “Her art encourages people to explore those feelings.”

Soon that art will be viewable on campus, inside Monmouth’s Rotary Ice House Gallery. In January 2025, Callas will open a solo show of “Ocean Bodies,” filling both the upstairs and downstairs spaces. She’s looking forward to showing her work to the Monmouth community, including her collaborators Delaney, MacDonald, and the other UCI scientists, as well as to her students. “It’s really exciting to share what I’ve been doing,” she says.

The exhibition will include “Whale Boat” and three other 10-foot works; the four-foot-tall swimmer drawings from Budapest; and large, 3-D-printed sculptures and other pieces from her “Ocean Bodies” series. “The scale is important,” Callas says, “because I want people to be immersed in the imagery.” She hopes to provide “a psychological experience,” prompting viewers to think about their own connections to other species and the ocean.

In talking about her work, Callas often calls it “uniting facts with feelings.” That, along with her personal connection to nature, is what drives her in all of this. “We have the science,” she says, “but people don’t act out of knowledge. They act out of feeling. To bring the facts and the feelings together is a big part of what I want to do in my art, my classes, and my Ecological Self work.

“I’m not merely aiming to illustrate nature,” she continues, “I’m interested in exploring our emotional attachments to nature and the process of how we create meaning out of the natural world.”