Under Review

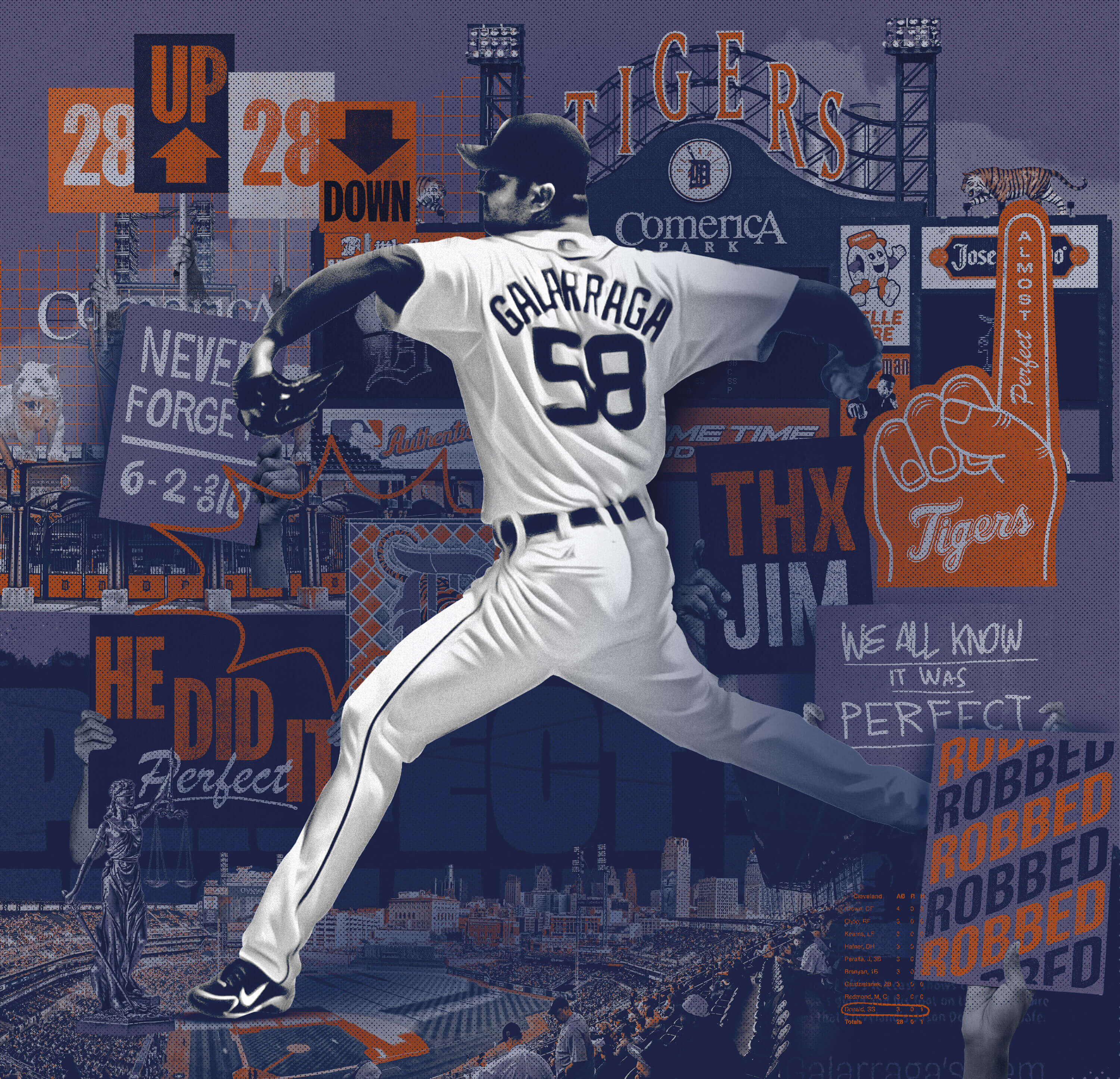

In 2010, a blown call robbed Armando Galarraga of a perfect game. Now, a Monmouth pre-law class is appealing his case to the commissioner of MLB.

When Hannah Latshaw enrolled in the Law and Society class at Monmouth University, she had no idea she would spend the semester studying something that happened in a Major League Baseball game.

“I definitely did not expect to write anything about sports in the first place,” said Latshaw, a senior psychology major who is minoring in sociology and criminal justice.

Yet that’s exactly what happened after Adjunct Professor Lawrence Jones began laying out his Fall 2021 class syllabus.

Law and Society—PO-364 in the Monmouth course catalog—aims to study “the evolution of law, social forces influencing law, social impact of law, and law as an instrument of social control and social change.”

Jones likes to bring in real-world examples and find ways for the students to produce work that can have an impact beyond the classroom.

In this case, Jones—a retired judge of the New Jersey Superior court and also a lifelong Oakland Athletics fan—turned to Armando Galarraga and the infamous almost-perfect game from June 2, 2010, the one where Galarraga lost a perfect game because of a blown call with two outs in the ninth inning.

Jones had seen coverage of the 10-year anniversary of the game, including a story in The Athletic in which Galarraga expressed hope MLB would one day recognize him with a perfect game. (Galarraga backed off that idea in subsequent interviews and later wrote on his website, “It would be very selfish to try to change the play, when errors have also happened in other important games.”)

Jones, though, remembered the game when it happened, as well as the reaction across the country. White House spokesman Robert Gibbs joked about using “the full force of the federal government” to have the play reviewed. The Michigan state House even made a proclamation declaring Galarraga had pitched a perfect game.

“What I remember most about it back in 2010 is the focus and outcry by so many people in the country who were not baseball fans, who didn’t even really know about baseball, that something was wrong here, that this did not make sense,” Jones said.

In teaching the Galarraga case to his class, Jones had the students read articles, watch videos, and do their own research. After some individual work, students broke up into teams—the Yankees, Red Sox, Phillies, and Mets—and began crafting deeper arguments. The students came to a near-unanimous resolution: that Galarraga should be awarded a perfect game.

The magnum opus of the class was an 80-page report filled with examples, precedents, and legal rhetoric arguing Galarraga’s case. The report was mailed to MLB commissioner Rob Manfred. Jones made sure to get a courier note as proof the proposal was successfully delivered.

“There were multiple reasons why I thought this would be an outstanding, excellent, thought-provoking exercise for the students,” Jones said, “in terms of studying law and society, in terms of studying the spirit of rules, the interpretation of rules, when results are equitable versus non equitable, and how not only courts but anyone in positions of authority have to generally have reasonable discretion to accomplish the right result. To me, the Galarraga case was a classic educational example for students, and they really, really immersed themselves in it and enjoyed it.”

In baseball circles, the idea of changing such a monumental call remains a controversial issue. MLB can be known for its rigid rules and a strict reverence for its history. Jim Joyce, the umpire who made the call, has expressed since the days after it happened that he would like for the call to be overturned. But even former Tigers manager Jim Leyland has never loved the idea of changing the record books.

“I think you just open up a can of worms,” Leyland said in 2020. “I think that would have been probably the worst thing to do, in my personal opinion.”

Students such as Tyler Kudrick, a sophomore majoring in political science with a concentration in legal studies, approached the Galarraga case with a fresh set of eyes. Kudrick, like many in the class, doesn’t follow baseball closely.

“(The research) just revealed a lot of idiosyncrasies within the MLB rulebooks and whatnot that aren’t necessarily modern enough to apply to the Galarraga case,” Kudrick said. “We looked at the idiosyncrasies of the rules. There was a lot of room, especially in Mr. Galarraga’s case, that it could have turned out differently if there were more wiggle room applied to the rules.

“It seemed like a lot of it was very cut and dry. But in the name of equity, it shouldn’t have been.”

The Monmouth students became more fascinated with Galarraga’s case after Jones arranged to have Galarraga join and speak to the class via a video call. Jones contacted Galarraga and explained the project, and Galarraga was happy to lend his time.

“He really connected with the students in a very, very humanistic way,” Jones said. “And that’s part of education. Students can read textbooks all day long. What it boils down to: Can they connect with people? Can they understand issues and have empathy for issues, and not just in a computer age where everything seems automatic and electronic? The human elements of an issue or a story become critical.”

In his meeting with the students, Galarraga shared his life story, tracing his path from growing up in Venezuela to experiencing both triumphs and struggles on baseball’s biggest stage.

“I thought it was amazing,” Latshaw said. “My heart just really hurt for him, honestly.”

“He sat there talking to us as if it was no big deal,” Kudrick said. “He had this almost-perfect game, as they call it, and he could have been in the record books, he could have been in MLB history. But he just accepted it.”

By semester’s end, the students compiled a detailed proposal that makes a compelling case for why MLB should recognize Galarraga in the record books. The report cites other incidents in MLB history such as the George Brett pine tar incident, Harvey Haddix in 1959, Hooks Wiltse in 1908, and more. It lays out an argument in a detailed yet levelheaded fashion.

“Students, particularly those who are interested in studying law, you always want to try to do the right thing,” Jones said. “You want to accomplish equity and fairness and justice. That’s what our whole system is about. The question is: How can that be done here? Can this be done in a way that’s reasonable and equitable and logical and consistent with the spirit of the game, the spirit of the rules, without causing any damage, so to speak?

“The presentation and proposal to the Major League Baseball commissioner accomplish all that in multiple ways, in an extremely reasonable, analytical, and thoughtful way.”

The legacy of the Galarraga perfect game, however, persists because of its complications, because of the fact it’s not actually recognized as a perfect game. As Joyce said in 2020, “Let’s face it. It’s a great baseball story.”

Such a great story that it’s now being taught at the university level.

“I’m definitely proud I’m part of something like this,” Latshaw said. “I’m very interested in law and everything that comes along with it. But never in a million years would I have imagined myself doing something like this. … Something I did could help somebody else and help them succeed and get the recognition they rightfully deserve.”

A version of this article originally appeared in The Athletic. It is reprinted here with permission.

Source images: Top: ARBITRARILT0/WIKIMEDIA; Middle: LEON HALIP/GETTY IMAGES; KEITH ALLISON/WIKIMEDIA; Bottom: NATIONAL BASEBALL HALL OF FAME & MUSEUM; DREAMSTIME; JOE VELL/ALAMY.