Reality Check

Nicholas Messina’s course on media literacy helps students embrace the curiosity needed to question their media consumption.

The most basic goal of formal education in society has long been to produce literacy, mainly in the three R’s of “reading, ‘riting, and ‘rithmetic.” But as society and its technology change, formal education needs to evolve.

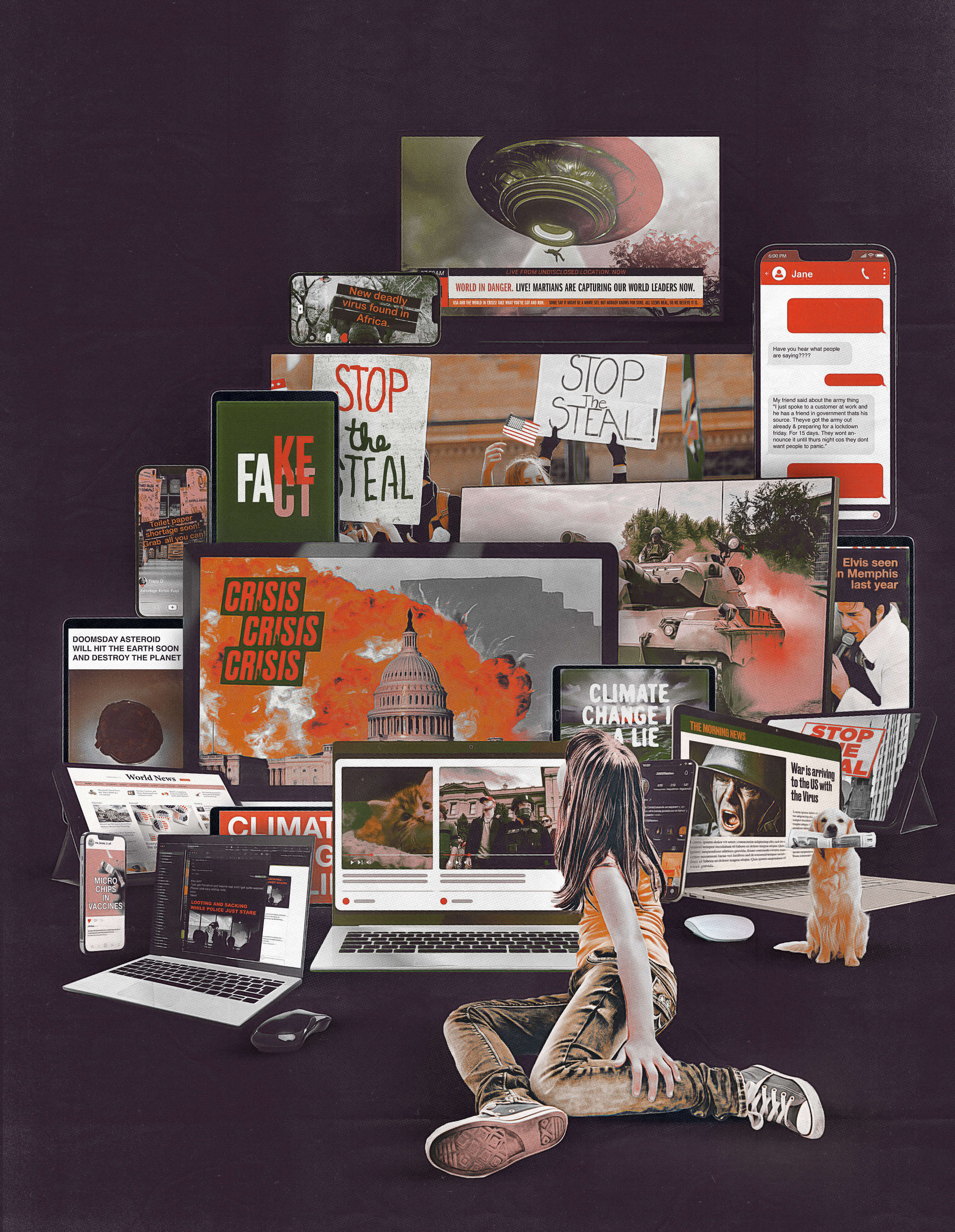

The most obvious form of technology that has impacted society today is the internet—and the deluge of media content it continually pipes into the minds of everyone everywhere on the planet.

Society has clearly embraced this new reality, as evidenced by recent Pew Research surveys showing that 85% of Americans go online daily, with 31% of adults and 46% of teens reporting they are “almost constantly” online. Yet the country’s educational institutions have been slow to incorporate media literacy into their curricula.

At Monmouth, Specialist Professor of Communication Nicholas Messina ’18M’s Media Literacy course (CO-155) helps students develop an understanding of the aesthetic, emotional, cognitive, and moral choices involved in interpreting media messages. We asked him recently why it is so important to be media literate in today’s world.

How do you get your students to start thinking critically about the media they consume?

The very first assignment I have them do is keep a journal for one full week in which they record all the media content they consume: radio, TV, billboards, advertisements, music streaming, social media. Once they realize how much content they’re actually consuming, it’s easier then to say, “OK, now that we realize how much we are actually being exposed to, let’s see what we miss.”

We can start to investigate some of the questions we don’t usually look into when it comes to media consumption. Who owns and controls the media? What are some of the economic implications of the media? What are the impacts of the constant flow on our perception of the world around us and on our perception of ourselves in that world?

Oftentimes, I’ll show them a television show episode or a movie and then have them break it down: What are our thoughts on the demographic imbalance? Why is it that we see more of this type of character as opposed to that type of character? Do we see any stereotypes? Do we think these are valid stereotypes?I try to have as free flowing a class as possible because having conversations is so important. Part of the issue that we experience in the way we consume media is that it all happens within a microcosm; it happens within these echo chambers.

So it’s really a matter of first saying, “Here’s what you’re already looking at, and these are what the implications are. Here’s what you could be looking at and hopefully sparking some curiosity. Try a different news outlet. Stop watching or listening to certain individuals.” But it’s incumbent on the individual to take that initiative.

What are some of the dangers of people not thinking more critically about the media they’re consuming?

The danger is taking everything at face value and believing that it is an unvarnished, untainted presentation of the truth. That can distort one’s perception of the real world.

For example, individuals who tend to watch more violent media content begin to believe that the world around them is equally as dangerous, when that is not the case at all. The types of crimes that are seen on television in certain cases are much more frequent in their depictions than they actually occur in real life. And this leads to the idea of “mean world syndrome,” where everybody’s out for themselves.

There’s also a lack of curiosity. Everything’s so fleeting—you continue to scroll and scroll and scroll, and certain ideas aren’t investigated further. They’re not being given the time and care they deserve. We’re looking for that next dopamine fix, if you will. So it really disconnects us from the physical world we’re currently living in.

Is there the possibility that people could become radicalized or fall for conspiracy theories because of their media consumption habits?

I don’t think people ever seek to become radicalized. It’s the algorithm of the medium and the way that these algorithms are set up—it continually feeds individuals this content whether or not they’ve asked for it.

They tend to have this assumption or belief that, since it’s been sent to me because I already watched X, then I guess Y and Z are perfectly OK to go ahead and watch—so they wind up falling down the rabbit hole without even realizing it.

To have this hyperexposure to media content—to live in such an oversaturated environment—and not ask some of the really pertinent and critical questions is a disservice not just to the individual but to society overall.

What are some of the positive aspects of having so much media content at our fingertips?

We see the ability to connect with certain subgroups and subcultures that one would not normally have access to. And it does make us at least aware of other things that are happening in other places.

It’s one of the reasons they cite for why public sentiment in Russia in regard to the war in Ukraine hasn’t been nearly as effective as it would have been in the past. People can simply see the reality of what’s happening on the ground in Ukraine, so they can’t just be fed state-run propaganda and take it at face value. There’s a completely different set of images that they have access to.

New Jersey recently became the first state to mandate that media literacy be taught in K-12 classrooms. What are your thoughts on this requirement?

I think it’s 20 years overdue. I think it’s paramount for students, especially at those younger ages, because we develop a regular pattern of consumption before we even enter school. By the time folks get to college, they’ve had 18 years of conditioning, and it’s up to us to address the conditioning that has happened and then try to instill the will and the desire to change that.

I do one particular lesson on Disney movies and Disney characters where I have students look back and think about some of the classic Disney movies that we’ve all seen. There’s nothing wrong with still liking them, but it’s important to at least acknowledge that there were certain things that were being reinforced that are probably not the greatest.

The materials used for the lesson include clips from films like Dumbo, in which there are characters quite literally named “Jim Crow,” begging the question about racial stereotypes and negative reinforcement. We have discussions about the potential underlying relationship messages in films like Beauty and the Beast, in which we see a young woman effectively in an abusive relationship. Instead of leaving the relationship, she stays and, through love and compassion, she’s able to “change” the beast, exposing the “prince” within. This has the potential to teach young girls that, hey, even if you’re in a troublesome relationship, stick it out and you can “change” that partner.

I had an undergraduate professor who said that you cannot unteach the people something, but you can teach them a new way to think about it. That’s what my goal is. We cannot undo students’ consumption patterns, but we can teach them to look at media and consume it in a different way.

What more needs to be done to foster a more media-literate citizenry?

I think media literacy should be a part of the general education experience even at the highest educational levels, full stop. I think it’s unfortunate that it’s not a mandatory class because it is, in many ways, the apex of intersectionality and interdisciplinary studies for a liberal arts education.

It’s a class in which we’re discussing individuals like Jean Piaget and the work that he did in early childhood development. We’re discussing the impact of political advertisements and political campaigns. We’re talking about the horizontal and vertical integration of media industries.

Basically, media literacy should be introduced to every school everywhere in the country as early as possible, and for as long as possible, because it is an ongoing process. One should never stop questioning what they’re consuming and what it does to us.

How does your course help Monmouth students after they graduate?

It sparks curiosity about others. It forces one to look more critically at themselves as well. Why is it that I have this particular opinion? Where did this potential bias develop?

I think it makes students better citizens of an increasingly global society when they can ask, why is the news presented in this fashion? What does it mean when this type of verbiage is used as opposed to this type of verbiage? How do I cut through the muck and the mire for verified factual information?

In general, they’ll be able to evaluate information in a critical way and distinguish between facts, points of view, and opinion, as well as understand the kinds of legal, social, ethical, and economic implications around the information that they’re consuming.

But the most important thing that the class teaches them is to embrace that curiosity instead of taking everything at face value. The underpinning of our entire country is questioning and investigating, and I think when we stop that, we find ourselves at a crossroads for democracy overall.