Partnership is the New Paradigm

In July 2016, Miami police officers shot a behavioral therapist, Charles Kinsey, while he was attending to a patient with autism. The patient, Arnaldo Rios-Soto, had run away from his group home and Kinsey was attempting to bring him back.

The police had received a 911 call indicating there was a man in the street with a gun threatening to kill himself. When they arrived, they found Rios-Soto sitting in the street and Kinsey standing next to him. Police ordered Kinsey to lay on the ground and put his hands in the air, which he did. Kinsey then told police that he was a behavioral therapist, and that Rios-Soto had no weapon, only a toy truck. But after Rios-Soto raised his hand, Officer Jonathan Aledda, a four-year member of the North Miami force who was on the SWAT team, fired three shots at him. Two missed, but one hit Kinsey in the hip. Aledda later said he thought Rios-Soto was holding Kinsey hostage and was going to shoot him.

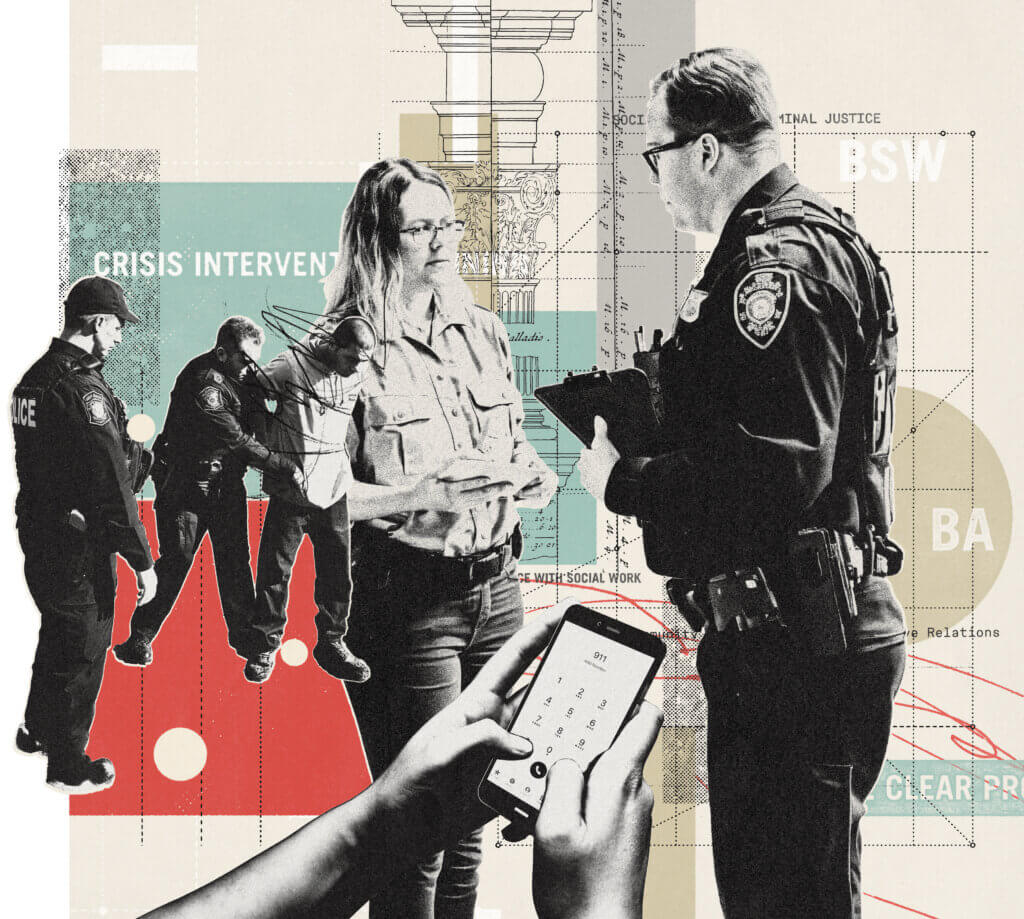

The incident was one of many across the country in the past decade that has led to increased scrutiny of how law enforcement officials respond to calls that involve people undergoing various mental health crises and has helped forge a growing consensus around the importance of using skilled crisis intervention as an alternative to old-school policing. As a result, law enforcement agencies are increasingly partnering with social workers to help de-escalate these types of situations, provide appropriate support, and connect individuals with mental health services.

In the fall of 2022, Monmouth University began offering an innovative dual degree program in social work and criminal justice that prepares students to handle the complex societal challenges that affect the safety and well-being of communities. The idea for the program came from Robin Mama, Ph.D., professor and former dean of the School of Social Work.

“The whole idea of this was to collaborate between our disciplines in an attempt to make changes in policing in our communities,” says Mama. “The combining of the bachelor’s programs is a way to begin to get the culture of the police and law enforcement environments to change and really think about how they work in their community, how they operate, and who else they can work with to be successful.”

The Impetus for Partnership

Though the program officially launched in 2022, Mama says the seeds of its inception were planted for her back in 2014, when Michael Brown was killed in Ferguson, Missouri, by police officer Darren Wilson. The incident ignited a series of protests that were marred by more violence due to what many in the community and across the nation saw as the militarization of the police.

“After that, I went to the criminal justice department and said, ‘We need to do something around this,’ and the conversation began on what we could do,” says Mama.

She quickly began connecting interested faculty from both departments to begin planning the new program. Mama also reached out to Doug Collier, a former DEA agent, who was working in the New Jersey attorney general’s office running the Community Law Enforcement Affirmative Relations (CLEAR) Program, a statewide continuing education initiative that requires annual training in de-escalation techniques, cultural awareness, and implicit bias.

Collier, who began his law enforcement career with the CIA, is now an adjunct professor and the director of professional outreach and engagement for Monmouth’s criminal justice department. He says it’s been exciting in the years since to work on the new program, which he feels is “going to prepare our students for what I call beyond the curriculum.”

“We want to make sure that our law enforcement folks understand the social work and counselor models, and that the social workers and counselors understand criminal justice, because we found that there was this void because we were so biased against each other,” says Collier.

Those long-standing biases are now changing, he says, thanks in part to law enforcement’s increased acceptance of programs such as crisis intervention training, in which police officers work with clinicians to understand how to handle someone with autism, for example, as well as a host of other mental health and social issues. Monmouth’s Department of Criminal Justice and School of Social Work cohosted one such program last spring, an event that attracted 80 law enforcement personnel from across the state.

“That was really well received, and they’ve been subsequently finding success,” says Collier. “I can tell you that, from my colleagues anecdotally, when they embedded a social worker in their departments, the calls for service decreased and providing services increased. They’re placing people where they belong—actually getting them help—whereas before we just threw them in a cell to protect them.”

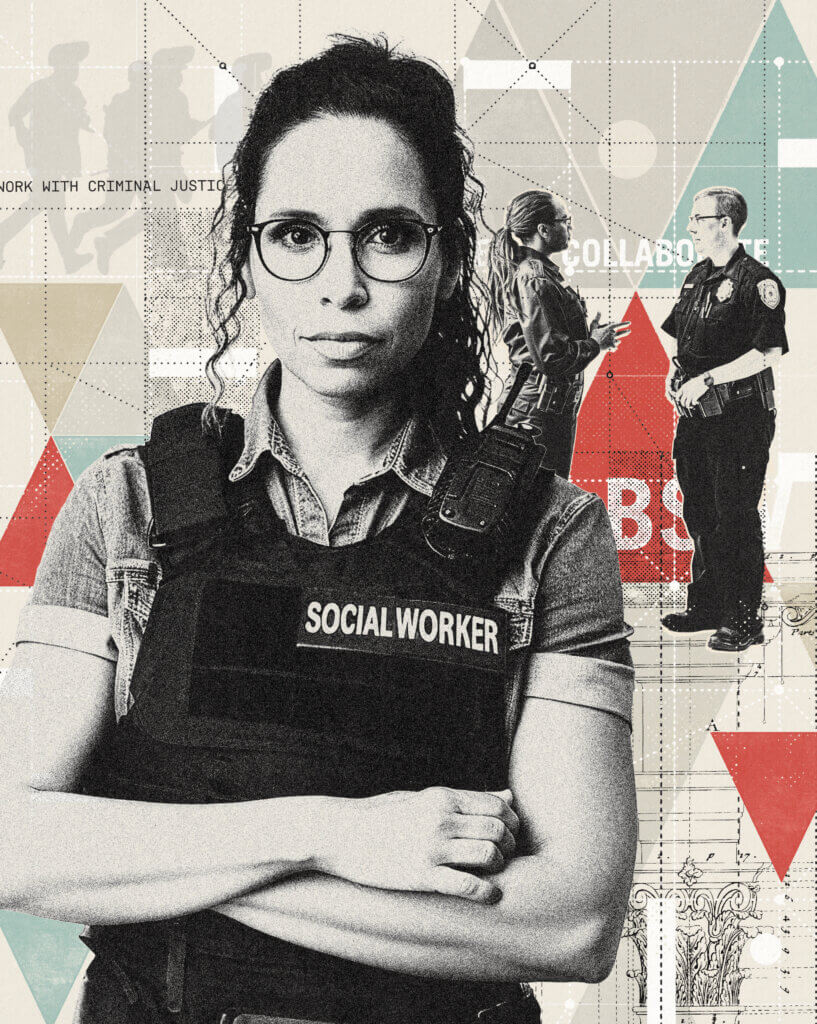

“Ultimately, our goal with this dual degree program is to prepare students in criminal justice and social work for the new paradigm, which is embedding our social workers and counseling folks into the criminal justice system,” says Collier. “And we’re really excited about that partnership.”

Preparing for the New Paradigm

Monmouth’s dual degree program combines foundational concepts from both disciplines. From the criminal justice side, that means required courses such as corrections, criminal law and procedure, and ethical issues in criminal justice. From the social work side, this includes coursework in social welfare policy and services; social work research methods; and social work practice with individuals, groups, and (most importantly, says Mama) communities. There are also opportunities for internships that combine both aspects of criminal justice and social work.

Students can graduate with both the Bachelor of Social Work and Bachelor of Arts in criminal justice. They will be well prepared to work in such fields as corrections, juvenile justice, rehabilitative services, and law enforcement departments and to continue their education by pursuing a master’s degree in criminal justice or social work, says Nick Sewitch, J.D., the chair of Monmouth’s Department of Criminal Justice.

“There are a lot of jobs that social workers can do without a criminal justice degree, and a lot of the jobs that a criminal justice major can do without a social work degree,” says Sewitch. “But we believe our graduates will be able to do those a heck of a lot better with both degrees because they’ll have both perspectives.”

A former assistant prosecutor for the Middlesex County Prosecutor’s Office for 29 years, Sewitch says there are relatively newer institutions in the criminal justice system, such as mental health courts and drug courts, that focus on incarcerating people for shorter periods of time and creating therapeutic communities in prisons. These institutions link offenders who would ordinarily be prison-bound to long-term community-based treatment, he says, and “you need people who have the training in both social work and criminal justice to do the kind of work to hook people up with resources.”

Additionally, says Sewitch, a new word has entered the criminal justice system lexicon in recent years: reentry.

“Before, when people were released from prison, it was up to parole to supervise all these people,” says Sewitch. “But they didn’t have the resources; the system was set up for failure. Now you have these nonprofit and for-profit reentry corporations throughout New Jersey, and social workers are needed to assist them from all different standpoints—drug therapy, hooking people up with social services, vocational counseling, mental health counseling.”

It’s not solely on the offender side of the law enforcement equation that professionals with expertise in both criminal justice and social work are needed, says Sewitch. Victims of crimes might also require services—families who lost family members to murder or to vehicular homicide, victims of domestic violence, victims of sexual assault, and so on.

“Every prosecutor’s office has a victim advocacy unit in it,” says Sewitch. “And while you don’t need to have a criminal justice degree or a social work degree to work in those units, we think it would be much more effective if the people in those units had expertise in both criminal justice and social work.”

Simply put, Monmouth graduates will have an edge in terms of getting hired for these types of positions within and without law enforcement and will be better prepared for the new reality of partnership that has emerged, says Sewitch.

“I think graduates of this program are going into, truthfully, a new environment,” he says. “They’re really carving a new occupational path, and it’s going to be interesting to see how this works.”

Promoting Permanent Change in Public Safety

Overall, the collaboration between law enforcement and social workers is seen by proponents as a holistic, community-centered approach to public safety, one that focuses on prevention, support, and long-term solutions rather than solely on reactive responses. They see the partnership as key to creating a more compassionate and effective system for addressing the complex challenges faced by communities.

That doesn’t mean there won’t still be challenges in creating and implementing this new paradigm.

Recently, Mama published the results of a study she conducted with Michelle Scott, professor of social work, and Stephanie A. Sabatini ’17, ’18M, in which they surveyed 335 leaders in law enforcement. Only about one-third of those surveyed believed a social worker was in fact needed.

However, more than 90% said a social worker would be helpful specifically with calls involving emotional disturbances, domestic violence, alcohol and drugs, and child endangerment, as well as for victims of crime and death survivors. Additionally, over 94% of senior leadership reported that an on-site social worker would support officers in facing their own emotional challenges, including alcohol and drug use and suicide risk.

There is a divide in the social work community around whether social workers should even be working with police, says Mama. There are some who feel that by working with law enforcement, they are condoning the bad behavior and contributing to—or at least perpetuating—the bias and violence that happens in communities.

Yet, there are many social workers who have been partnering with police for a long time who say that, when they’ve collaborated with and educated law enforcement personnel on the social issues they are dealing with (domestic violence, for example), they have been able to effect real change, says Mama.

“Realistically, we can’t get rid of the police—we have to have police in our communities, because there are safety and other issues that police deal with very effectively,” says Mama. “But what we can do is change the cultural attitudes there around how you deal with people and how you work successfully in all communities—and make them [police] more effective by being better communicators and not jumping for their guns at the first instant.

“Our whole goal has been to say, ‘Look, if there’s going to be police reform, the more we collaborate, the more we’re going to make permanent change.’ And to do that, it starts with education.”