Many Happy Returns

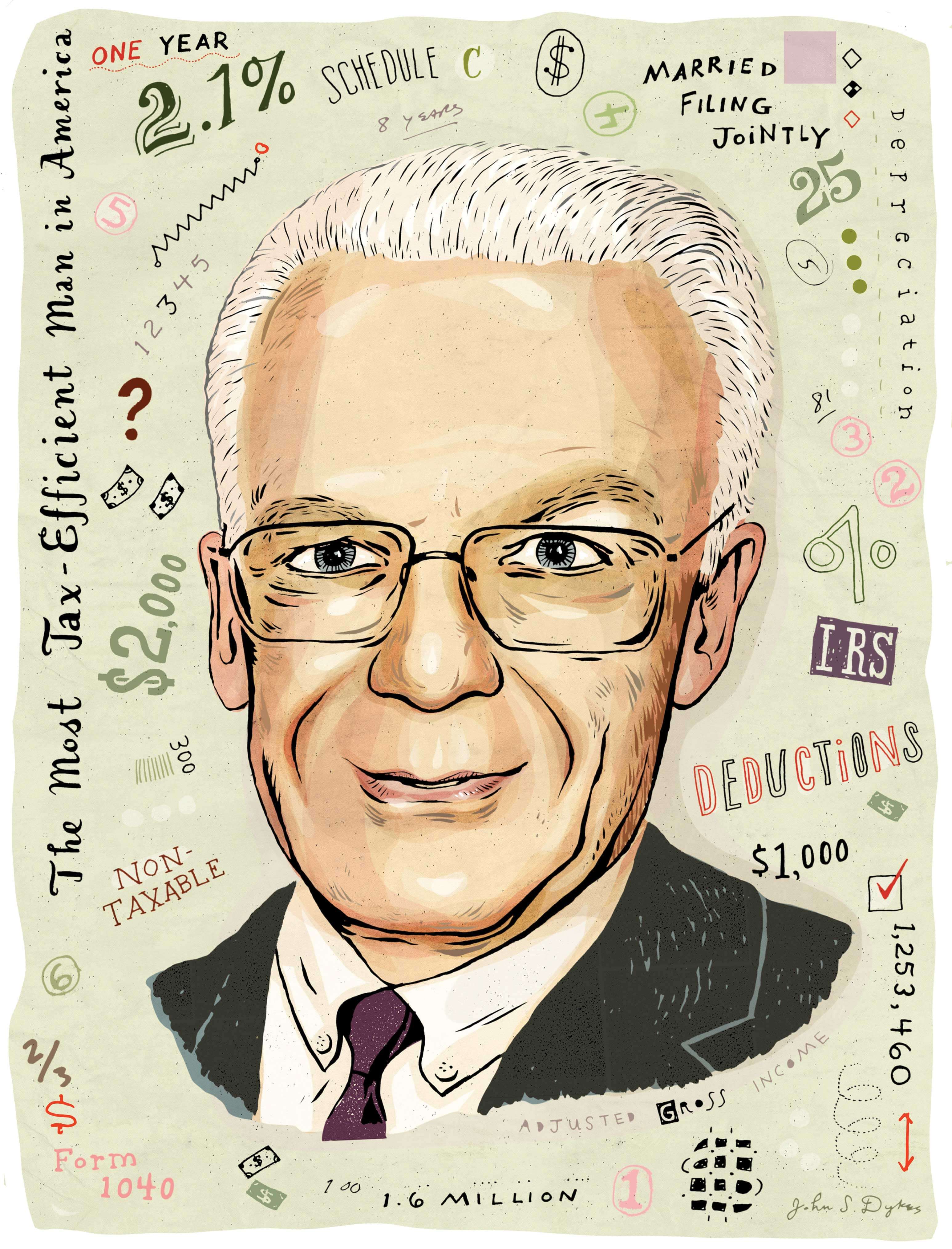

Talking taxes and more with Doug Stives, CPA—“The Most Tax-Efficient Man in America.”

Specialist Professor Doug Stives spent 36 years at a public accounting firm before joining Monmouth’s faculty in 2006.

Five years later, The Wall Street Journal bestowed the title “The Most Tax-Efficient Man in America” on him because of his decades of experience as a CPA and the ways his nuanced and meticulous use of annual deductions, benefits, and professional autonomy allows him to “live a fuller life.” Stives talked with us about how he first fell in love with accounting, what the new federal tax law could mean for filers, and how you should never do your taxes by hand.

What led you to a career in accounting?

I took five years at Lehigh University to get my bachelor’s and M.B.A., but when I got there, I didn’t even know what “CPA” meant. I originally wanted to become an engineer, like my father. Nonetheless, my studies in engineering weren’t working out, and this was the ’60s, so you didn’t drop out, or you got a one-way ticket to Vietnam. The only thing I really enjoyed was my accounting class. It was different. It wasn’t more math, or science, or history—I always said that if I took another history course I was going to get sick [laughs]. Accounting wasn’t easy, but I was able to get it. I started to see it as the language of business, and like learning any new language it’s not fun in the beginning. But the more I learned, the more I liked it.

Why do you think the subject clicked for you?

I think it was because I was always fascinated with business. As a kid I would look up stock prices in the paper. One time, I visited a family friend who was a stockbroker in New York, and we watched the tickertape come off the machine. I was captivated, even though I didn’t understand it all. My father was also fascinated with finance, and we would sit and read annual reports together.

You worked for several decades in public accounting before joining Monmouth’s faculty. What did you come to realize about the profession in that time?

Accounting is a foreign language; it’s also an art. It’s not a science. I teach my students this. I’ll say to them, “OK, you just elected me treasurer of your organization. Do you want me to give you good news or bad news?” And they’ll say, “Just give us the numbers.” And I’ll say, “No. Do you want me to show a profit to shareholders and a loss to the IRS?” I’m not talking about breaking the law; I’m talking about understanding the language of business. An accountant isn’t there to just add up numbers. Anyone can use a software program to do that. An accountant needs to put talent and experience together to assess who the information is being tallied for and what that information will be used for.

Do your experiences from that time trickle down to your students?

I teach by telling stories. Sure, I show PowerPoints and go over homework and prepare students for exams. But I don’t go 10 minutes without saying, “Let me tell you about this experience I had.” I use that technique in my continuing education courses as well. It adds value and my students aren’t just watching a video.

So your approach is a combination of theory and practice?

Absolutely. Students need both. I think some schools in accounting have gone a little too far in practice. For instance, my students don’t ever do a tax return in my classes because the forms change, the laws change. I want them to understand the theory behind the practice. I don’t do my own tax returns, the software does. But if you don’t understand what the software is doing, you’re lost.

Let’s talk about that title, “The Most Tax-Efficient Man in America.” How did that come about?

I wasn’t keen on that title, actually [laughs]. But here’s The Wall Street Journal writing about some CPA from New Jersey—already you’re off to a bad start, because it doesn’t get any duller than a CPA from New Jersey—but they were looking for a way to get readers interested in this tongue-in-cheek, front-page article. And they said, “What do you do that’s different?” Well, I get a W-2 from Monmouth, and I get benefits. I used to pay for my own health and life insurance. All pension money came directly from me. But as a full-time employee of the University, those things are now covered. I even get a 10 percent discount at the bookstore and free tickets to football games.

Then, on the side, I have Doug Stives LLC, which is my vehicle for teaching continuing education classes across the country. For that work I get a 1099. So I told [the Journal] it’s the best of both worlds. I get benefits from the college side and then deduct on my tax return things like my Wall Street Journal subscription, my computer, Wi-Fi, my cellphone, continuing education, and some travel expenses. You can’t do that as an employee. They twisted it around in journalistic fashion—which I admire—and came up with the title.

That article says you “use the tax code’s many quirks” as the means through which you “can live a fuller life.” How so?

Tax laws are complicated by their nature. Congress writes them—and Congress can’t do anything without complicating it. As a professor, I know what you can do—not what you can get away with—what you can do to reduce your taxes legally. I’d be a fool not to take advantage of those things. And the more you do it, the better you get at it. I’m careful. I know what records I need,and I know what to back up and what will survive an audit.

The article also mentions “the flurry of tiny deductions that add up,” explaining how you write off things like allowable mileage and food expenses on business trips—even down to a hot dog you bought at the airport. Are there things the average person doesn’t understand about deductions?

Deductions can be very beneficial. However, one of the things I’m constantly telling my students is that just because you can deduct it from your taxes doesn’t make it free. There’s so much misinformation out there. You have people who brag about being in the top tax bracket or who brag about not paying any taxes at all. That tells you a lot about a person.

Also, some people think that because they work from home, they can deduct part of their house. Well, no, there are very strict rules about that. People are doing stuff they shouldn’t, sometimes intentionally and sometimes because they lack information.

This is the first year that people are filing under the new tax law. What should the average filer know heading into this season?

For a lot of people, tax returns are simple. They get a W-2, and unless they are afraid of computers, they get a software program and file that way. By the way, don’t ever do your return by hand. That’s stupidity.

As for the new law, a lot of people won’t itemize deductions this year. Many people are reverting to standard deductions. And if you don’t have more than $24,000 (for married taxpayers) in deductions, there’s not a whole lot you need to know.

What about someone whose return might be a little more complicated?

If you have investments, a business, or rental properties, then you really need professional help from a CPA. And you need to meet with that person one-on-one. Unfortunately our profession has morphed into just scanning your W-2 and other forms. Then the accountant processes your return and sends it back to you for filing. Don’t do it that way. You don’t call a doctor and just tell him what’s wrong over the phone, right? When it comes to finding an accountant, you have to insist on some kind of personal meeting, at least the first time.

People should also be aware of the new Qualified Business Income deduction, which, if you have your own business—within certain parameters—you won’t pay taxes on 20 percent of what you make. This law simplified taxes for a lot of people but made it unnecessarily complicated for others. But we don’t have nearly enough time to get into all of those complications [laughs]!

Any other tips?

If you hear from the IRS, get professional help before you respond. The IRS is not the Middletown police. They don’t read you Miranda rights. You open your mouth, say the wrong thing, and you could go to jail.

What do the next few years look like for you?

More of the same wonderful stuff, really. I know it can’t go on forever. I’ve tragically seen people who don’t know when to quit, and I don’t want that to happen to me. My memory is not as good as it used to be. I need more sleep. My hearing is terrible. My eyesight’s bad [laughs]. I think I’ll give myself another four or five years in the classroom. But I still like to ski and sail. The last thing I’ll ever do is sit around screaming at the television. But right now I am just exceedingly happy doing what I’m doing.