Larger Than Life

Brian Hanlon ’88 sees his subjects—athletes, coaches, mascots, religious and historical figures—from a unique perspective.

Everything changed when Bob Roggy died. It was August 1986 and the Holmdel, New Jersey, track star was ascending toward the peak of his athletic career. Having set the American record in javelin just four years prior, Roggy was firmly ensconced on the national track and field stage, with his sights fixed on competing in the 1988 summer Olympics. But that dream came to a sudden and tragic end when Roggy was thrown from the back of a pickup truck in Houston and died a few hours later. He was 29.

Brian Hanlon ’88 was beginning his first year at Monmouth as an art education major when he heard about Roggy’s death. The news hit him especially hard. Hanlon had grown up with Roggy in Holmdel, attended the same high school as the track star, and he felt immediately moved to pay tribute to the young man. So Hanlon shuttered himself in his dorm room and began working on a clay sculpture.

“The whole town was in shock. And I was just moved to make that sculpture for the sake of tribute and remembering,” recalls Hanlon from the bright, sunlit interior of his home office in Toms River, New Jersey.

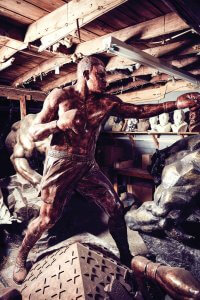

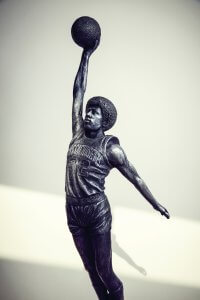

In the 32 years since that moment Hanlon has gone on to become the United States’ premier sculptor of athletes, coaches, mascots, and celebrated moments in both sports and American history. He’s the official sculptor for the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame and the Rose Bowl. And he’s been commissioned to render more than 500 pieces over the course of his career—which can be found everywhere from Los Angeles to Puerto Rico and dozens of states in between—including nuanced and evocative bronze sculptures of legends like Shaquille O’Neal, Evander Holyfield, Jackie Robinson, and Yogi Berra.

But back in 1986 Hanlon was just an unassuming Monmouth undergrad with a tenuous notion of the future ahead of him. “I didn’t have any formal training when I did that piece for Roggy,” he says. “I just did it from my gut.”

Using an image from the cover of Track & Field News showing Roggy about to release a javelin from his intimidating right arm, Hanlon worked tirelessly on the piece. Less than a year later it was unveiled in a formal ceremony at Holmdel High School—where the two-and-a-half foot bronze likeness remains to this day—and it was there, at the unveiling, that Hanlon knew his life would never be the same.

“I’ll never forget the look on Mrs. Roggy’s face that day. It was a look of momentary mercy. Of letting go, even for just a few seconds. She’d been on my mind the entire time I was working on that sculpture and she was the only thing that was important to me in that moment,” says Hanlon. “If you know that your art has the potential to make that kind of difference, then you must pursue it. And it was in that moment that I knew what I would do for the rest of my life.”

Hanlon never aspired to become an artist, even though he had an almost instantaneous and innate talent for working with clay that was fostered and encouraged by his high school art teacher.

“Clay was easy for me. It wasn’t just some pile of mud. I realized early on that I could actually makes things out of it. And it made me feel like Superman,” says Hanlon, who’s as perpetually bright and enthusiastic as he is contemplative about his work. “It was also striking to me that clay came from the earth, and I always felt some strange connection to it. But never in a million years did I think I’d become an artist. I just didn’t see the practical application at all.”

After high school Hanlon embarked on a somewhat aimless and potentially dangerous path. Without any college plans, he spent several years employed as an ironworker in New York and then as a teamster at Monmouth Park Racetrack. The money, he says, was “really good.” But the lifestyle—which included an ongoing struggle with substance abuse—was slowly eroding away his mind, body, and spirit.

“I wasn’t focused on becoming a contributor to society whatsoever. I was bad news, man. I was not a good citizen. I was mostly a trouble to myself, and I realized that I was destined to just crash and burn,” says Hanlon. “Eventually I looked around and thought, ‘This is not what I’m supposed to be doing with my life.’”

So he decided to hit the reset button and enroll at Monmouth as a 25-year-old freshman, and it was there that a series of revelations washed over him, providing him with a dawning sense of humility, courage, and purpose. After completing the Roggy sculpture he abandoned his plans to become a teacher and doubled down on his own sculpting, which led him to create his second piece—The Involved Student.

It’s his favorite to this day, and it depicts a young woman lying on her back reading a book, her right leg propped up by a soccer ball, her head resting peacefully on a gym bag. Hanlon’s then-girlfriend and now-wife Michele (née Adamkowski ’90) modeled for the sculpture, which is located outside Woodrow Wilson Hall, and the meaning behind it still has a powerful resonance for the 57-year-old artist.

“I wanted to create something that embodied my experience as a student at Monmouth,” says Hanlon. “If you’re involved in government, athletics, and academics, that’s a worthy experience. I never knew that until I felt it myself. I wanted to put that into a sculpture.”

Three decades later, Hanlon has once again lent his artistry to Monmouth’s campus with a gargantuan bronze sculpture of the University’s Hawk.

Measuring 15 feet high with a 22-foot-long wingspan, the 29,000-pound sculpture was unveiled this fall on Brockriede Common. It was a gift to the University made possible through generous donations from Hanlon and the Brockriede family (including Monmouth University Trustee John A. Brockriede Jr. ’07, ’10M). No university funds were used for the sculpture, which Hanlon says he created to represent much more than athletic pride.

“This isn’t just about the physical hawk. It’s about the symbolism and the energy and enthusiasm of students, alumni, faculty, and anyone else who passes by. It’s not about sports. It’s about creating and fostering spirit,” says Hanlon. “Monmouth gave me a new start on life. I discovered the talent and courage to pursue the artist’s life at Monmouth. That was a profound experience, and that’s the energy I put into making this sculpture.”

~

It’s an uncharacteristically cool, breezy August morning as Hanlon sinks into a comfy loveseat and sips his daily glass of pressed juice. He’s still buzzing from the ELO concert he attended at Madison Square Garden two nights ago with his brother Al.

“We were walking to our car and I just kept saying, ‘Why do I feel so damn happy?’ It’s that music, man,” he says. “Every single song was a hit. Every song. It was beautiful.”

Hanlon unfurls an infectious smile punctuated by a burst of high laughter, his signature glee always right around the corner. He could just as easily talk about music—or American history, or the trees in his yard, or the joys of his family—as he could about his own artistic pursuits.

A mounted television that faces Hanlon’s desk plays ESPN on mute and an in-ground pool in the backyard paints his large windows with soothing shades of blue, casting wisps of watery reflections against the ceiling and walls. Various paintings of his five children dot the interior landscape. This is where Hanlon does his design work, and nearly every corner of the office contains evidence of his long, celebrated career as a master sculptor, with dozens of miniatures resting on shelves, tables, and even the floor.

There’s a miniature version of the James Naismith statue that stands outside the Basketball Hall of Fame in Massachusetts.

There’s a miniature of the life-size statue of Boston Celtics point guard Bob Cousy, which stands in front of the Hart Recreation Center at Cousy’s alma mater, Holy Cross. There’s another miniature, this one of college basketball coach Jerry Tarkanian seated on a bench clutching a towel between his teeth, which mirrors the eight-foot-tall bronze installation that Hanlon did for the University of Nevada, Las Vegas in 2013.

And there, inconspicuously perched on a nearby table, is a small sculpture depicting John Elway’s famous helicopter leap in Super Bowl XXXII, which Hanlon hand-delivered to the legendary quarterback’s home a few years ago. He says he eventually hopes to make a larger installation of it for the Denver Broncos organization.

But despite the eye-popping nature of his subjects, Hanlon is not your stereotypical fanboy. Sure, he’s rubbed shoulders with some of the most celebrated names in American sports, but he’s not interested in the vaunted mythology of the individuals he sculpts—or even in the games in which they competed. He’s interested in the stories behind the athletes and the moments they helped create.

“Yes, I get to do some really cool stuff for some cool people, but I’m more of a social scientist than I am a sports fan,” says Hanlon, who is currently in the middle of an astounding 17 sculpture projects in this second half of 2018. “I’m fascinated by the culture of stadiums and athletics. When I unveil a statue at a stadium I don’t usually even go to the game. I stand outside the stadium and I watch the people coming and going. I’m more interested in everything that leads up to the game than I am in the game itself. I’m not into the rah-rah and all that, and I think that’s why my perspective is so effective. It’s the unearthing of stories and moments that gets me out of bed every day.”

For instance, Hanlon recently completed a memorial statue of LSU running back Billy Cannon that will be unveiled at his alma mater in late September. To college football fans, Cannon is interesting because of his athletic accomplishment as the only Heisman Trophy winner to ever come out of LSU. But what Hanlon finds most fascinating is Cannon’s life story.

After retiring from the NFL Cannon started a successful dental practice, but he fell into financial turmoil due to bad real estate investments and a crippling gambling addiction. The football star eventually got wrapped up in a counterfeit money racket and wound up printing more than $6 million worth of hundred-dollar bills in his basement. He served nearly three years in federal prison, and after his release he decided that he wanted to start practicing dentistry again—but this time he’d do it at the same federal prison in which he’d been recently incarcerated.

“He wound up doing that for 45 years! Now that’s what I call a redemption story,” says Hanlon. “That Cannon sculpture is one of the most interesting projects I’ve ever done. Not because of the athletic accomplishment, but because of the story behind the man. And I love the backstories, man. I love them even more than I love the statues.”

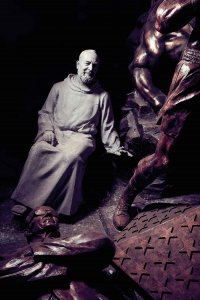

Hanlon’s refined ability to see his subjects from a unique perspective goes back to his time spent working on a fine arts master’s degree at Boston University, which is where he landed after graduating from Monmouth. While there Hanlon was commissioned to create a statue of Saint Francis for the Church of Saint Leo. After that he was commissioned to sculpt a statue of Saint Mary in Marlboro, New Jersey, and then another bust for a church in Rumson shortly after that.

“Suddenly my schoolwork was getting in the way of my professional work, and I had to decide if I was going to work hard for a grade or work hard for a paycheck,” he says. “I chose the latter.”

And so, early in his third semester at B.U., Hanlon packed up his things and came home to work out of his mother’s garage in Manahawkin, where he became increasingly busy sculpting liturgical statues for churches throughout the region. And that was his exclusive area of focus for the next 10 years—crafting detailed, evocative works of religious art that not only reflected the individuals but also the passions and stories they carried in their hearts.

Eventually he “upgraded” from his mom’s garage to a cold, dark, dirt-floor cemetery garage in Toms River, where he remained for a while before eventually settling into the 3,000-square-foot abandoned chicken coop that remains his studio space to this day.

“When you’re sequestered in a cold garage and crawling around on the freezing ground by yourself, knowing that these statues are your only source of income, you’re humbled every day,” recalls Hanlon. “That’s how I really learned my craft. That’s why I’m here. Now I’m doing the things I’ve always wanted to do, paying tribute to interesting historical markers and moments.”

Hanlon’s body of work isn’t confined to the world of athletics. It’s remarkably diverse and includes several sculptures honoring first responders and American tragedies, including a 9-11 memorial called Angel in Anguish, which was unveiled in 2011 to honor eight residents of Brick Township who died on that infamous morning 17 years ago.

He’s also currently working on two historical pieces—a seven-foot-tall statue of Harriet Tubman for the Equal Rights Cultural Heritage Center in Auburn, New York and an eight-foot-tall bronze installation of Susan B. Anthony that was commissioned in April by the Adams Massachusetts Centennial Celebration committee. The Anthony piece will feature two depictions of the celebrated suffragist—one of her as an adult speaking atop a flight of steps with her childhood likeness sitting at the base reading a book.

“I do research on everyone I sculpt, and in the case of Susan B. Anthony I wanted to create a link between her reading as a child and the way that made her into the strong woman and public speaker she became,” says Hanlon. “That’s more than just a sculpture. That’s telling a story.”

Admittedly, those stories are sometimes emotionally draining for the artist.

“It was emotional sculpting Billy Cannon. I met with his daughter and she cried to me,” recalls Hanlon. “And the piece I did for Brick? When I started that project I met with a widow who was pregnant with the child of the husband she lost on September 11. I was eventually hospitalized for dehydration while I worked on that piece because I wasn’t eating or drinking. I was so consumed by it. I’m not a priest or a rabbi. I’m an artist. I’m not wired to hear some of the things I hear. But that’s what you do sometimes to capture the truth of a piece.”

Despite the physical and emotional toll of his work, Hanlon shows no signs of slowing down. After all, there are still so many subjects left to sculpt. For instance, he has a miniature of guitarist Duane Allman that he one day hopes to do for the city of Nashville. And another of Amos Alonzo Stagg, one of the founding fathers of American football. In the meantime, Hanlon remains propelled day after day by perpetual gratitude and disbelief at the life he’s managed to sculpt for himself and his family.

“I was walking through Monmouth’s campus just the other day thinking about the Hawk, and I was hit by this wave of emotion. Like, Whoa! How did this happen? Why me? Why didn’t someone else get this gift?” he says. “But art is so much bigger than us, and it always will be. I’m going to be a little blurb in history as far as my contribution to art. And it’s only when you understand your size and your humility that you can really make a difference. When you think you’re bigger than the stories or the art itself, you will always fail. Always.”