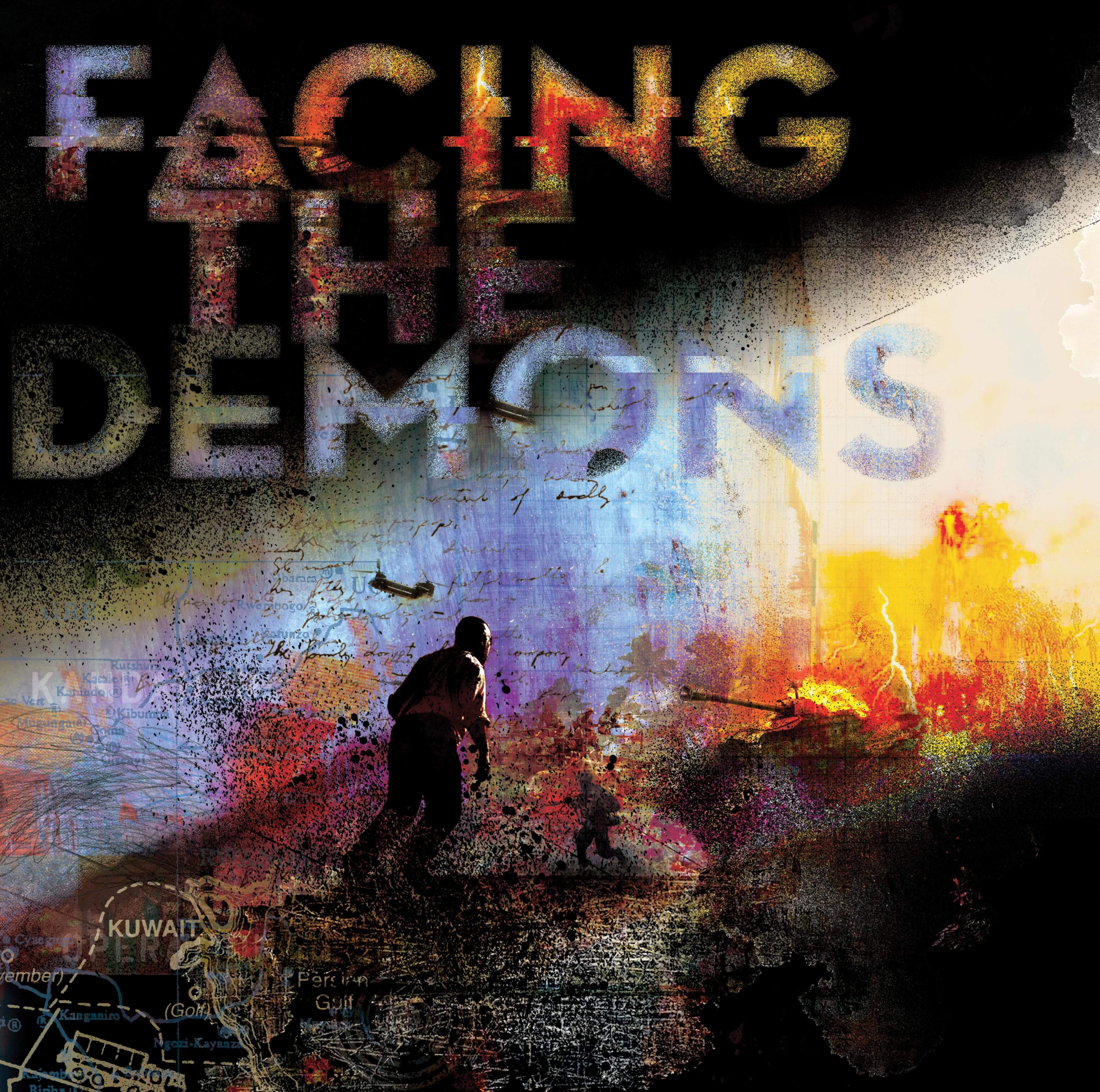

Facing the Demons

Christian Benedetto Jr. repressed his PTSD until it was almost too late. Now he’s a resource and advocate for others coping with the disorder.

By almost every measure the party was a grand and cheerful affair. A large tent was set up in the backyard, a jukebox had been rented for the evening, and more than 100 people showed up to celebrate the homecoming of Christian Benedetto Jr. ’89, who had just spent the better part of the past year serving as a United States Marine in Operations Desert Shield and Storm. Gathered at his parents’ home in Middletown, New Jersey, friends and family laughed and smiled with delight at seeing the 24-year-old safe and sound, showering him with frequent hugs or pats of congratulation on the back. But as the night grew later, Benedetto’s father couldn’t shake the feeling that something wasn’t quite right with his son.Walking over to Christian and putting an arm on his shoulder during a lull in the celebration, he asked, “You OK?”

“Sure,” said Benedetto, surveying the party with a detached, faraway look in his eyes. “I guess it’s kinda surreal for me. Just trying to take it all in.”

Surreal indeed. The nine months spent on the front lines had been an arduous and ceaseless journey comprising equal parts fear, adrenaline, and exhausting vigilance. Not only had he witnessed the jarring and often sudden violence of war, but he also hadn’t slept inside a building in more than seven months and had been afforded the luxury of a shower only once during that same time. And just five days before his homecoming party he was stationed at an agricultural compound in Saudi Arabia, waiting for the slow, tedious gears of his deployment to churn in the direction of home.

Now, as if in a flash, here he was, standing in his backyard with a mind trapped thousands of miles away.

“Are you sure you’re all right,” his father asked again, this time with a little more insistence in his voice.

“Yeah,” he said. “Why do you keep asking me?”

“Well, you’ve got more than 100 people here. And we’ve got four bathrooms inside the house. But all night you keep walking over and taking a piss in my flower beds.”

Like waking from a dream, Benedetto snapped to a realization. He hadn’t used a proper bathroom in more than half a year. Like every other soldier, he had become accustomed to simply walking 50 feet and doing his business wherever he could find spare ground. And that’s what he was doing now, subconsciously reverting to the crude, indelicate routines of military life in his parents’ backyard. Until his father said something, it hadn’t even occurred to him to use the bathrooms inside. And while he breezily dismissed the moment with a chuckle, Benedetto couldn’t help but wonder if the episode signaled something dire about his state of mind.

Over the next few weeks he continued struggling to adjust to everyday life. He couldn’t sleep in the house, so he’d go out to his parents’ deck and spend his nights on a lawn chair with nothing but a pair of shorts and a thin sheet to cover him. One night a major thunderstorm rolled in, but instead of moving inside, Benedetto simply flipped two chairs over and slept beneath the makeshift shelter. Sometimes he would even dig a hole in the yard and spend evenings curled up in the cool, familiar earth. And he was also drinking. A lot.

“I knew something was wrong,” recalls Benedetto, now 50. “But there was a lot more going on.”

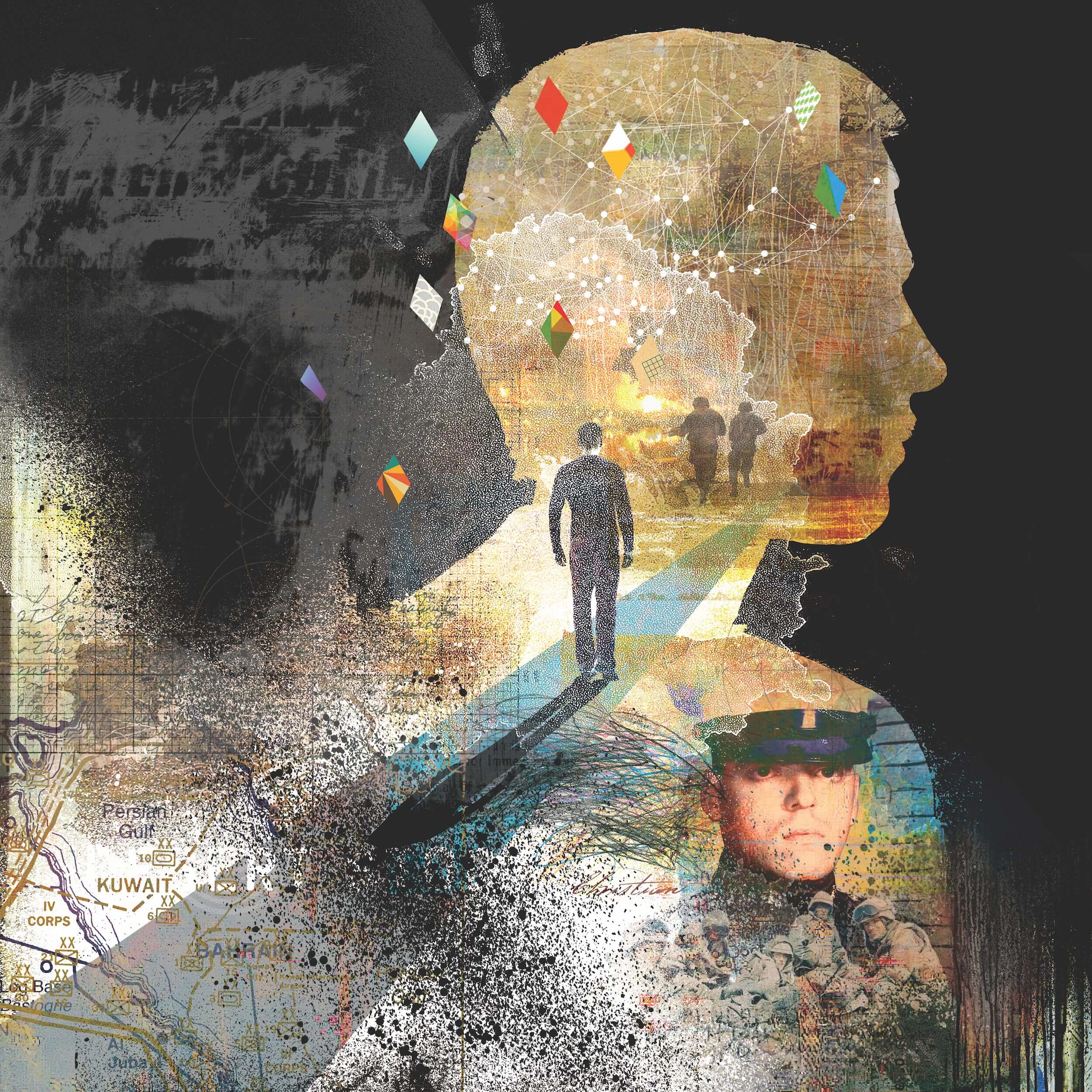

It’s been more than two decades since that memorable homecoming, and the journey hasn’t been easy. Wrestling with the demons of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Benedetto has emerged from a darkness that once threatened to consume him, soberly and honestly accepting his condition while also serving as an enthusiastic voice of advocacy and support through PTSD Journal, a magazine he founded last year to educate and help others who suffer from the crippling condition.

But before he could help others he first had to help himself, and that meant experiencing moments far darker than nights spent sleeping beneath deck chairs or relieving himself in his father’s flower beds.

“Here’s the paradox about being a Marine,” says Benedetto. “The best thing is that you’re tough as nails. Nothing bothers you. You can deal with anything. But guess what? That’s also the worst thing about being a Marine. You never think you need any help. I had no idea what struggles were ahead.”

When Benedetto enlisted in the Marine Corps in December 1989 after earning his undergraduate degree in financial services from Monmouth, he did it because he “wanted more from life than a wife and a starter home with three and a half bedrooms.” He wanted to see the world. It was during his time at boot camp that Desert Shield got underway, and Benedetto was enthusiastic about the opportunity to eventually serve his country overseas. And for the first few weeks of his deployment everything progressed more or less as he’d imagined it would, with a few notable exceptions.

When Benedetto enlisted in the Marine Corps in December 1989 after earning his undergraduate degree in financial services from Monmouth, he did it because he “wanted more from life than a wife and a starter home with three and a half bedrooms.” He wanted to see the world. It was during his time at boot camp that Desert Shield got underway, and Benedetto was enthusiastic about the opportunity to eventually serve his country overseas. And for the first few weeks of his deployment everything progressed more or less as he’d imagined it would, with a few notable exceptions.

“I had some preconceived, romantic notions from the movies. Some of them were true and others were definitely not,” says Benedetto. “For example, one of my jobs during the war was to drag 55-gallon drums from under the privies into the desert, pour diesel fuel in them, and burn the waste. That definitely wasn’t in the brochure.”

Benedetto doesn’t care to share specific horror stories from his time overseas, but looking back, he is unflinching about tracing his PTSD back to that long, interminable stretch of time spent in the theater of desert warfare.

“My PTSD comes from being in really, really cramped places that were really, really hot while things are blowing up all around us,” says Benedetto. “And then there was the sleep deprivation. You’re up every night for a few hours and then up and at it the entire next day, cleaning weapons, digging holes, always on alert. All of that starts to take its toll. To this day, I still can’t sleep for longer than an hour and 45 minutes at a time.”

Benedetto’s military service eventually came to an end in 1994, at which point he decided to go into sales, a career lifestyle perfect for hiding the demons lurking beneath the surface.

“I was the life of the party. A former Marine! OK, so he drinks a little too much, but who cares? He’s bringing in deals. And I was good at it,” says Benedetto. “I could drink while golfing, wine and dine clients, and entertain business partners at casino bars. And nobody thought anything of it because I was just this big, fun-loving war vet. People cut me a lot of slack.”

But when he was alone the walls came down. In addition to drinking himself to sleep, Benedetto was also becoming increasingly paranoid, wracked by panic attacks, and thrust into nightmares almost every time he closed his eyes. He would sometimes barricade his basement door or hide behind his living room couch and keep watch for no specific reason other than to obey the crippling whims of his untamed anxiety.

By 2007, he knew something had to change. He’d recently gotten married, and he and his wife were already making plans to have a child. He stopped drinking and built a life of sobriety that’s now lasted 10 years. And yet he had not come to terms with the disorder that was ruining his life.

“I just didn’t want to deal with it,” says Benedetto of his then-repressed PTSD. “I did whatever I wanted to. I wasn’t considerate of anyone’s feelings but my own. And it wasn’t until I was 38 that I started to realize life actually had consequences.”

The final turning point came one early Saturday morning in the fall of 2013. Benedetto and his now ex-wife were lying in bed when their 5-year-old son came into the room at 6 a.m. asking to sleep in their bed. Eventually Benedetto and his son fell asleep, and the moment should have passed as an otherwise peaceful and happy one. But then his son stirred suddenly in his sleep, jarring Benedetto from a nightmare and causing him to instinctually grab the boy’s wrist with frightening and unconscious intensity. Emerging from the fog of sleep, Benedetto was horrified, and later that day he made a call to his local Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) office. It was time he admitted that he needed help.

“My son’s nine now, and he doesn’t even remember that moment. And even at the time I think it scared me more than it scared him,” recalls Benedetto. “But that’s when I knew I had to do something, because either I was going to manage my PTSD or it was going to manage me.”

PTSD statistics for service members are often sobering and staggering. According to the VA, about 12 percent of U.S. troops who served in Desert Storm have been diagnosed with PTSD (compared to 20 percent of soldiers from the most recent theaters in Iraq and Afghanistan, and 30 percent from Vietnam).

What’s more, NBC reported in 2016 that U.S. military suicides hit a record high in 2012 when more than 349 military men and women took their own lives (a higher number than those lost in battle that same year). That number dropped to 265 last year, and while overall awareness of the disorder has risen throughout the past decade, many who specialize in the treatment of PTSD and general trauma say there is a long road ahead.

“This is one of those topics in mental health that hadn’t been very well understood for a long time, and there’s still a lot to learn,” says Tom McCarthy, assistant director of counseling and psychological services at Monmouth. “And the more we try to understand PTSD, the more we understand how pervasive and detrimental it is to a person’s life. It doesn’t just go away after combat. It stays with the person and affects every single level of their life.”

This is the message Benedetto has been trying to broadcast ever since that fateful morning in 2013. In addition to maintaining his sobriety, Benedetto has been getting regular treatment from the VA, which includes a combination of medication and counseling. And while he still encounters triggers—unannounced, spontaneous circumstances that can ignite debilitating panic attacks—he now knows how to recognize and manage them through breathing and mindfulness.

“PTSD robs you of your dignity, and it robs you of any ability to really just function in the world,” says Benedetto. “And the thing is, you don’t get better. You get less worse.”

Help and healing, he says, are made that much more difficult by the persistent, lingering stigma PTSD still has within the military community and beyond, which Benedetto likens to “where same-sex marriage was seven to 10 years ago.”

“People still think admitting you have PTSD means you’re not strong enough, but in fact you get PTSD from being too strong for too long,” says Benedetto. “I literally had someone come up to me once and tell me that his grandfather fought in World War II and that he was just fine, so what kind of wuss was I to say I had PTSD? That’s what we’re still dealing with.”

To that end, Benedetto founded PTSD Journal in the summer of 2015, which bears the tagline “Not all wounds are visible.” The idea came about when he first started seeking treatment and discovered there weren’t any periodicals dedicated to this pervasive and critical topic. Since then he and his publishing partner have released five issues, each dedicated to improving the quality of life for PTSD sufferers and their families. Functioning as a veritable advocate for the PTSD community, the biannual journal comprises a mixture of research articles, personal essays, and myriad service pieces highlighting the causes of PTSD and the tools needed for recovery and healing.

And the journal is not limited to combat-related PTSD. According to Benedetto, PTSD can arise from a wide variety of traumas, including sexual assault, domestic abuse, car accidents—even unexpectedly witnessing a distressing event. Statistics related to non-combat PTSD are hard to come by, but according to the Post Traumatic Stress Disorder Alliance, about 70 percent of U.S. adults have experienced a traumatic event at least once in their lives, and up to 20 percent of those go on to develop PTSD. What’s more, an estimated 5 percent of Americans have PTSD at any given time, and about 8 percent of all adults—1 in 13 people—will develop some level of PTSD.

“We’re trying to help people, to raise awareness, and to engage in meaningful interactions with our readers,” says Benedetto, adding that the magazine’s Facebook page receives a steady stream of traffic and user comments. “We’re touching people’s lives on a daily basis.”

Outside of the magazine, Benedetto is tireless in his personal outreach, publicly offering his cell phone number to anyone who feels like they need to reach out for help. It’s all part of his new appropriation of the PTSD acronym: Please Tell Someone Directly.

“If you have PTSD or feel like something is wrong, don’t waste any time. Tell someone how you’re feeling,” says Benedetto. “And if you think someone you know is acting a little odd or depressed or angry or drinking too much, talk to them about it. I’m sharing my story not so I can come across as a professional victim with a sob story. I’m doing it because I want people to get the help they need—the same help that I needed for so long.”