Drawn Out

Frank Gogol’s early life was a series of painful setbacks. His father died of a drug overdose before he turned 2. His mother, who also struggled with addiction, did her best to support them by working multiple waitressing jobs, but they moved around often.

Gogol enjoyed a relatively stable home life for a few years after his mother met his stepfather. There were Christmases spent as a family, birthdays that had gifts. But his stepfather also struggled with substance abuse, and when Gogol’s mother relapsed around the time he turned 12, he was sent to live with family friends. When they were no longer able to take care of him, he was placed in a group home where he remained through his teen years up until the week before he moved in at Monmouth. During his freshman year, Gogol received word that his mother had been hit by a car and was in a coma; she died a few months later.

“If I had known then what I know now, I may have realized things were a little bit more off,” Gogol says of his upbringing, which seemed mostly normal to him. “My mom—she wasn’t the best person, but she was a good mom. She really did bust her butt working two to three jobs making sure I was taken care of.”

An anchor in the chaos for Gogol was the fictional worlds provided by books, comics, and cartoons. He was an avid reader and vividly remembers buying his first comic book at the Rite Aid in Hazlet’s Airport Plaza in 1997. “I think having those colorful characters like the Ninja Turtles and Spider-Man growing up, they were helpful in keeping me young when there were things going on around me that would maybe make other people have to grow up a little faster,” says Gogol.

His love of reading led him to take as many English courses as he could in high school, and it was there that he first felt inspired to write. For an honors class, he had to read Their Eyes Were Watching God. A key passage in the book, in which the main character decides to leave an abusive relationship and lets her hair down for the first time, resonated with Gogol.

“It’s sort of on-the-nose poetic. It’s symbolic of her having her freedom—her hair is no longer up in this tight thing; now it’s down and free like she is,” says Gogol. “When I took that in, I really fell in love with what stories can do.”

He enrolled at Monmouth as an English major with minors in creative writing and graphic design, earning his bachelor’s in 2010 and, a year later, his master’s in English with a focus in creative writing. He quickly found a job in marketing but floundered on the creative writing front, he says. He knew he wanted to write but was unsure what to write about. “I was having a lot of false starts: talking a lot about wanting to be a writer, trying, and then not getting really far.”

Then in early 2015, Gogol had an aha moment. Feeling unfulfilled at work, he was reviewing a conversation he had with a friend on Facebook Messenger that had spanned years. When Gogol saw how long he had talked about wanting to be a writer—without actually doing much writing—he realized it was time to “fish or cut bait.” With the blessing of his then-girlfriend now fiancee, Catherine, he quit his job to figure out exactly what it was that he wanted to do.

He freelanced at first and then, thanks to a gift from Catherine, enrolled in a class offered by Comics Experience, an online comic book school. For the class, he had to write a five-page script. That story, “Embrace,” is a snapshot into the life of a father struggling to connect with his autistic son. Gogol, whose cousin has autism, combined his own worries of parenthood with stories his aunt had told him of the struggles faced by parents raising children on the spectrum. Within two weeks of the class ending, he had found an artist, colorist, and letterer who turned the script into a complete illustrated comic within 10 days.

“Once I had that finished story, and I could read the script next to the finished pages and say, ‘This is my thing,’ I really—there’s no better word for it, but I—got addicted to it,” says Gogol.

Encouraged, he set out to expand his portfolio. He wrote a few stories back-to-back, writing each in a different genre to flex his creative muscles. When he had six stories finished, he laid the scripts across his office floor to look for holes in genre and style that he could fill with additional stories. He noticed a pattern.

“I was moving things around, moving stories next to each other, and I realized that these stories—sometimes directly, sometimes a bit indirectly—addressed the stages of the grieving process,” says Gogol. He hadn’t consciously set out to write about grief but thinks that because of his life experiences, the grieving process had become somewhat ingrained in him through the years. (Not to mention, he particularly loved a comic book miniseries called Fallen Son: The Death of Captain America, which included five stand-alone stories of Marvel superheroes grieving the death of Captain America.)

“That was another one of those touchstone moments for me, not as a writer but as a person, because I had all of this stuff happen to me, and sometimes I’d dealt with it, and other times I hadn’t,” says Gogol. “This sort of gave me a framework to understand what I had been through and what I was going through up until that point in my life, and it really was just very helpful to me in a weird way.”

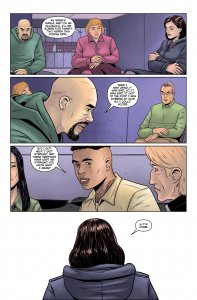

Gogol ran with the idea and rounded out the collection with 10 stories in total—two for each of the five stages of the grieving process. The stories span genres—from drama to horror, magic to superhero—and while all address the topic of grief, many also tackle current social issues. “Different,” for example, is about a transgender woman struggling to find her place in the world. She succeeds by finally accepting who she is and uses her painful experiences as a springboard to create a better version of her life. Another story, “Prayer,” features a woman in a Narcotics Anonymous meeting expressing how her financial struggles make it impossible to buy her son a Christmas present. When she leaves the meeting, she finds a box of presents sitting on her trunk (see illustration above). Gogol says “Prayer” is plucked straight from his childhood—but it was his birthday, not Christmas, and rather than buying him presents, his mother’s NA group chipped in to buy him a cake.

While several of the stories touch on dark themes, highlighting the harsher moments of grief, some, like “Prayer,” are ultimately stories of hope.

“You know that the mother’s and son’s lives are not going to get markedly better between that story and the next morning, or maybe the next year, but the universe sort of provided for them in that moment,” says Gogol. “It’s realistic—it’s not perfect—but it’s hopeful… and that is kind of how my life has gone.”

Once he had 10 stories written, Gogol paid over $3,000 out of pocket to have them produced by professionals. He sold collector comic books to pay for a large portion of that cost and then started a Kickstarter campaign to recoup some of the cost and to get the content out so that people could read it. Supporters who gave $1 or more would receive a PDF download of the finished product: GRIEF, the anthology. He launched the campaign in April 2017, and to Gogol’s surprise, supporters surpassed his goal of $1,500 within the first 10 hours. A few months later, Source Point Press approached him with an offer to publish GRIEF in paperback form.

Print copies of GRIEF are available online, and Gogol also sells them at conventions. While doing so at New York Comic Con, he experienced a touching moment with a fan. A trans man who had purchased GRIEF the day before returned after reading the story “Different.” The man broke down, crying quietly on the convention floor and thanked Gogol for showing a trans character in both a positive and accurate light.

“I do want to be a socially conscious writer… and I’m of the opinion that stories should be useful to people in some way, shape, or form, either entertaining, or they should learn some lesson from it,” says Gogol. “And if we, as a society… talked about [grief] in a more positive way and embraced it and were more open about it, then I think we’d be better off for it.”

No longer unsure what to write about, Gogol says he’s at work on several books. But GRIEF will always hold a special place for him.

“This is the kind of book I wish I’d had when I was growing up. I think I would have done things differently with my own grieving process, and healing, and growing up,” says Gogol. “And that has 100 percent been my experience talking to people—that is what [GRIEF] is doing for people, and that’s what brings me the most happiness by far.”