Dispatches From the Front Lines

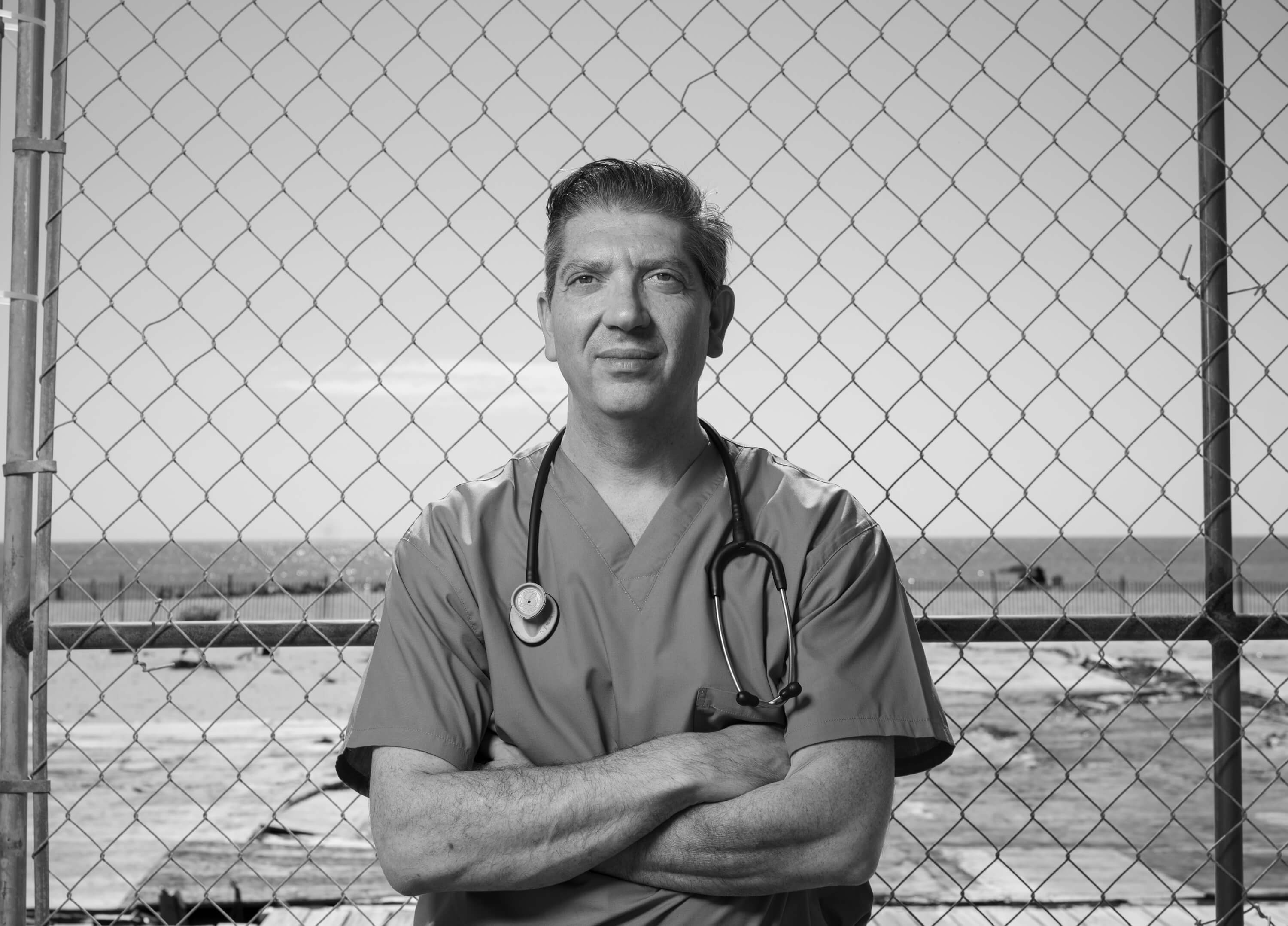

A pulmonologist takes on COVID-19 in the ICU and on social media.

It was the second week of March when the unavoidable, intense reality of COVID-19 hit home for Dr. Jeffrey Miskoff.

As a pulmonary, critical care, and sleep medicine specialist, Miskoff had been forced to close his office at Shore Pulmonary in Ocean Township as he and nine other doctors from the medical group shifted their focus to intensive care units at Jersey Shore University Medical Center, where Miskoff serves as chief of pulmonary medicine. It was an all-hands-on-deck situation comprising long, exhausting days trying to understand the novel virus and devise the best treatment options for infected patients. And it was during that first week of the outbreak that Miskoff recalls treating one particular, younger physician.

“Luckily this man wound up doing very well, but there was a point when he was pretty sick with COVID in the ICU. I think that’s when it hit home for me,” says Miskoff, who graduated from Monmouth University in 1993. “I’m 48 years old, and seeing a doctor younger than me get that sick really struck a chord. If it could happen to him, then it could happen to me.”

Unfortunately, this was only the beginning of a tense, confusing, and sometimes macabre journey that would unfold as Miskoff spent March, April, and much of May helping to diagnose and treat COVID-19 patients. In the context of his 20-plus years as a physician, Miskoff says, “I’ve never experienced anything like this…or the angst associated with it.”

I’ve never experienced anything like this…or the angst associated with it.

To be sure, Miskoff’s angst was multifaceted and nuanced. Yes, there was the overarching concern of becoming infected, but this actually paled in comparison to both the stress of the unknown and the peripheral humanitarian sorrows he witnessed throughout the spring.

“In March, we really just didn’t understand the virus, and in those early days we were all very fearful when hospitalizations ramped up because we didn’t necessarily know how to deal with it,” says Miskoff, recalling how protocols, treatment suggestions, and hospital management often changed on a daily basis. Additionally, Miskoff says more than 90 percent of newly admitted patients were suffering from COVID-19 in March, and all 10 hospital floors were being used in some capacity to diagnose and treat them. “When every case is COVID and nothing but COVID for a month straight, it starts to give rise to anxiety, and I think there will probably be some PTSD from those who worked closely with very sick patients.”

For Miskoff, the most emotionally taxing aspect of working on the medical frontlines came from seeing such a high volume of patients on ventilators. More specifically, Miskoff points out that when patients are ventilated, they’re placed on their bellies to allow for better oxygen circulation, a procedure that led to a surreal landscape of extremely sick individuals suffering in veritable anonymity.

“Everyone was flipped over and heavily sedated, and all the patients just started looking similar. I experienced some anxiety with that,” says Miskoff. “And then you add to it the fact that these people were severely sick but also alone because family weren’t allowed to visit. I just kept thinking how traumatic that must have been for patients’ loved ones.”

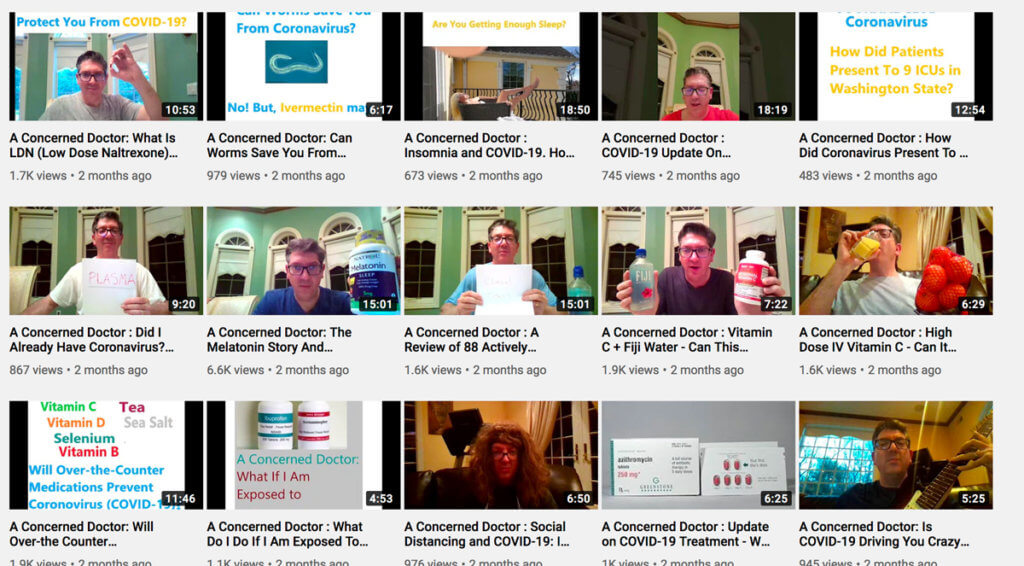

Despite the chaos and emotional turmoil into which Miskoff had been unexpectedly flung, he decided that he wanted to do just a little more, which is why he started a YouTube channel during the second week of March called “A Concerned Doctor.” It was an admittedly uncharacteristic move for someone who is “not a big social media guy” and who didn’t even know how to use YouTube before March 14. Nonetheless, the spontaneous project—which features Miskoff talking directly to his webcam from the comfort of his Toms River, New Jersey, home—has proven to be both valuable and therapeutic to himself and others.

“I think initially it was helpful for me. In the beginning there was definitely some self-reflection. I also saw it as a journal of sorts, where I could create a record for myself and others to watch as the situation unfolded,” says Miskoff. “But I’ve now seen how it’s been helpful to others as well, and over the past few months I’ve run into maybe 20 or 30 people who have thanked me for doing it.”

Thus far Miskoff has more than 1,000 subscribers and has posted close to 40 videos, most of which focus on statistical analyses of potential COVID-19 treatments while also trying to answer specific questions that crop up in public discourse. And while the overall topic may be serious, Miskoff does take the occasional opportunity to insert some levity. For instance, he started one of his early videos by playing the opening riff from Black Sabbath’s “Crazy Train” on his unplugged electric guitar. The title of that video: “Is COVID-19 Driving You Crazy?” In another video from late March, Miskoff can be seen wearing a long, voluminous, unruly wig, a site gag used to accentuate the importance of social distancing—even if it means you can’t visit the salon.

Notably, Miskoff avoids using his videos to make predictions or insert himself into the myriad political elements that have inevitably played a role in how the U.S. is handling the pandemic. For him, it’s all about the science of studies, treatments, and new information.

“Here’s the thing. Clinicians don’t look at this like the rest of general society. I don’t care if this thing was created in a lab or it came from Mars. We have patients we need to heal,” says Miskoff. “And I try consciously to not project where we’re going. We just don’t know. So most of my videos have a question mark in the title. Will this particular treatment help you? Will x, y, or z be the silver bullet? I didn’t want to be controversial. I wanted to be comforting.”

Speaking in late May Miskoff says the worst of the outbreak seems to be behind him for now, and he’s looking forward to reopening Shore Pulmonary in June to begin telehealth consultations with non-COVID-19 patients.

“I’m happy that I was able to help when I did, but I certainly don’t want to continue as nothing but a ‘covidologist’ for the rest of my life. I think that would be somewhat depressing, because I trained for pulmonary and sleep care. Things like asthma and narcolepsy and sleep apnea. And I very much like taking care of those other types of patients,” says Miskoff. “Patient care was definitely delayed because of the virus, and we now need to get back to taking care of those people as well.”

As to whether or not Miskoff considers himself a hero, the doctor quickly demurs.

“I actually feel that there many other people more deserving of that title than myself. From a cerebral standpoint we gave a lot of our brainpower to figuring out what may be the best treatment. But the ones with higher risk of exposure are equally, if not more, heroic,” says Miskoff. “For instance, the nurses didn’t come up with a regimen of medicines to give, but they had to go into rooms with very sick people on a repetitive basis, and I believe that put them at a much higher risk than myself. I’ve tried to live my life humbly, so it’s difficult labeling myself as anything other than a man on this earth. I was no more of a hero than anyone else in that hospital.”