Dispatches From the Front Lines

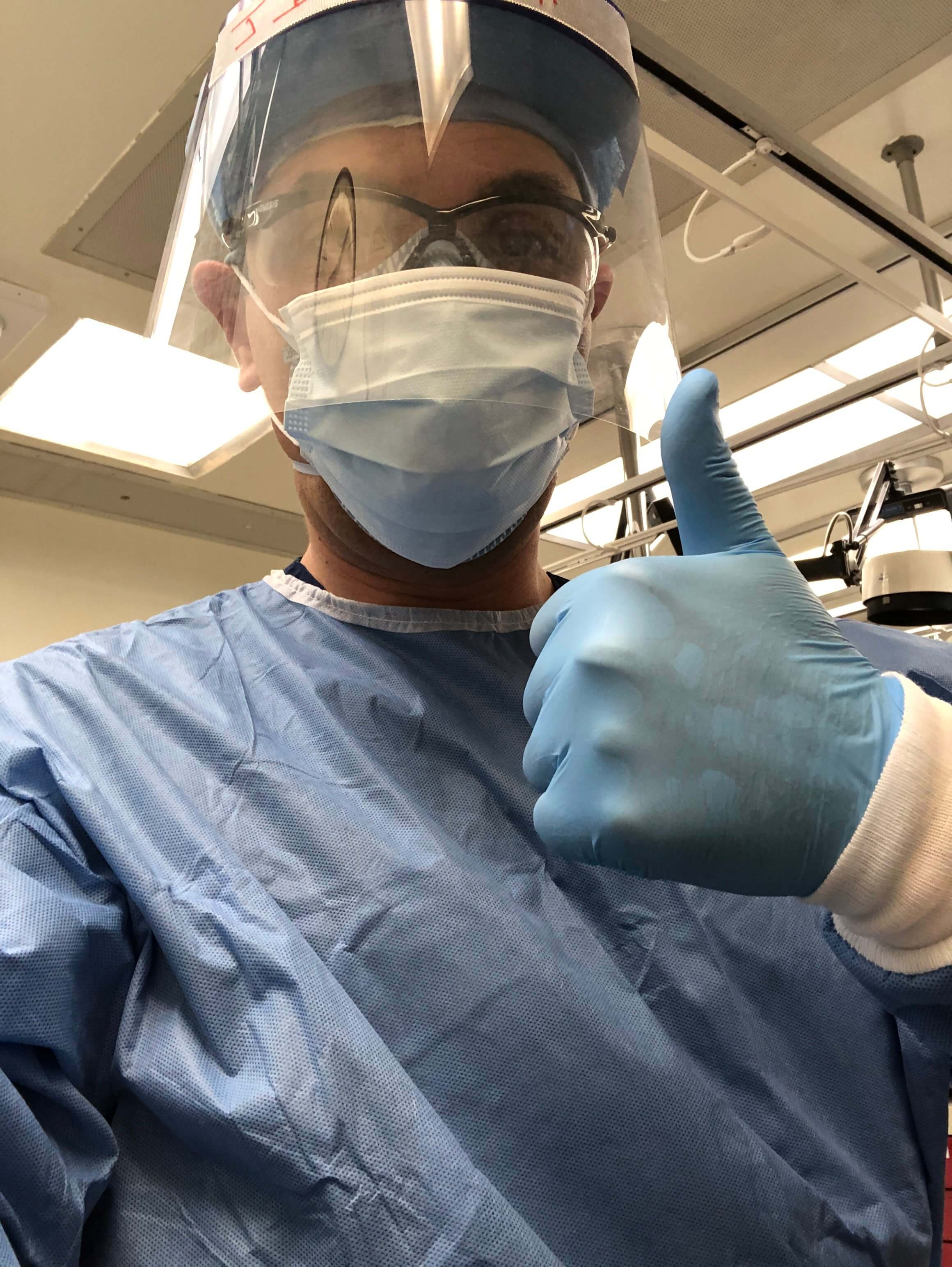

Nurse practitioner Kristopher Jackson, a 2009 health studies graduate, spent most of his career working in intensive care units before moving into an acute care setting in 2019. This past April, he took a leave of absence from his job at the University of California–San Francisco Medical Center to volunteer in a New York City hospital during the peak of the outbreak. He was stationed in the Bronx, a place the Washington Post labeled “New York City’s coronavirus capital.” He shared some of his experiences with us.

Early on in the course of the COVID-19 pandemic, my clinic work was scaled back substantially. I was doing very few in-person visits and many routine follow-up visits were being conducted via telehealth. I heard on the news that while New York City had done a good job of mobilizing a workforce of healthcare providers to help, they were shorthanded when it came to providers with ICU experience. Thankfully that wasn’t the case here in San Francisco. The more I thought about it, something just felt inherently wrong about me sitting at home with less work than ever before when I, an experienced critical care provider, could be on the front lines in New York. I felt like I could be of service where it was most needed, and that was really the driving force behind my decision.

Under normal conditions, a hospital operates as a series of neatly organized departments, each of which has its own niche. Based on my experiences in the Bronx, and from what I’ve heard from colleagues who volunteered in other New York City hospitals, these delineations become less clear during a pandemic. When I arrived in New York, there were still a large number of hospitalizations happening, and partner hospitals in the area were sending patients who needed beds. So we were scrambling to meet that need while making additional critical care space for the patients decompensating within our own institution. During my time in the Bronx, we used every square inch of available space to increase the hospital’s capacity of critically ill patients.

One of my first days there, I was working in a large, post-procedural space that had been converted into a makeshift ICU. There were 15 or so patients on ventilators there. I received, in transfer, an elderly woman with multiple comorbidities; she was really struggling to breathe and I had a grim feeling about how her story would end. It felt wrong to intubate her and prolong her suffering, only for her die on a ventilator. I thought it best to make her comfortable in the event her condition worsened. I called her husband to share my impressions and see what her wishes would be, because she couldn’t tell me herself. At first, he was appreciative I had called. However, gratitude turned quickly to rage. “It’s Tuesday,” he said. “I brought my wife to a hospital—in Queens—last Thursday. They took her from me and I haven’t known where she was since. I’ve been sitting in my house watching footage of bodies in tractor trailer trucks wondering if she’s inside one of them. And now you’re telling me that my wife of 30 years is going to die alone in a hospital because I can’t be with her.”

Honestly, I’ve made a thousand phone calls to families to tell loved ones of a patient’s death in the middle of the night or to discuss next steps because I thought further escalations in care would be futile. Those calls are never easy, but there’s a way to approach them. No amount of experience can prepare you for having to tell someone that their loved one will likely die alone because it is unsafe for anyone to be by their side.

Eventually one area of the hospital became my home, sort of like my little ICU with my patients and a consistent team of contracted staff and volunteers. The mainstay for COVID therapy right now is still supportive care: making sure the patients are getting appropriate ventilator care, making sure that certain physiological parameters are being met. These patients are prone to decompensating quickly, but if they’re doing well not a lot happens. They also tend not to recover quickly, so it’s constant assessment and monitoring.

There were supply shortages. We ran out of things like hospital beds. There were times when I wanted to order another medication for a patient and was told we didn’t have another IV pump to put it on, or I needed a specific medication and was told we didn’t have any of it. Each day came down to doing the best we could with what we had to keep people safe, and to try to ensure a certain quality of care. I think this is where having critical care experience was monumentally helpful. This experience gives you the latitude and knowledge base to be creative in providing care. Much of the contracted workforce brought in to aid in the pandemic response efforts had never set foot in an ICU before and that posed some struggles. Overall, I’m proud of the care we gave despite not having a conventional space, conventional supplies, conventional ventilators—all of the things you’d expect in a 21st century ICU.

The professionals who work in that hospital and other hospitals in the Bronx full time are the true heroes. Many of them had COVID and recovered and came back to work. Many had family members they weren’t able to go home to see after their shifts were over. There were multiple staff who had family members admitted to the hospital in which they were working; they were still showing up to work their 12-hour shifts. There was a sense of moral duty and obligation amongst the staff in the hospital that I found inspirational. It embodies why we chose this profession and why we have dedicated our lives to it.