Dispatches from the Culture Wars

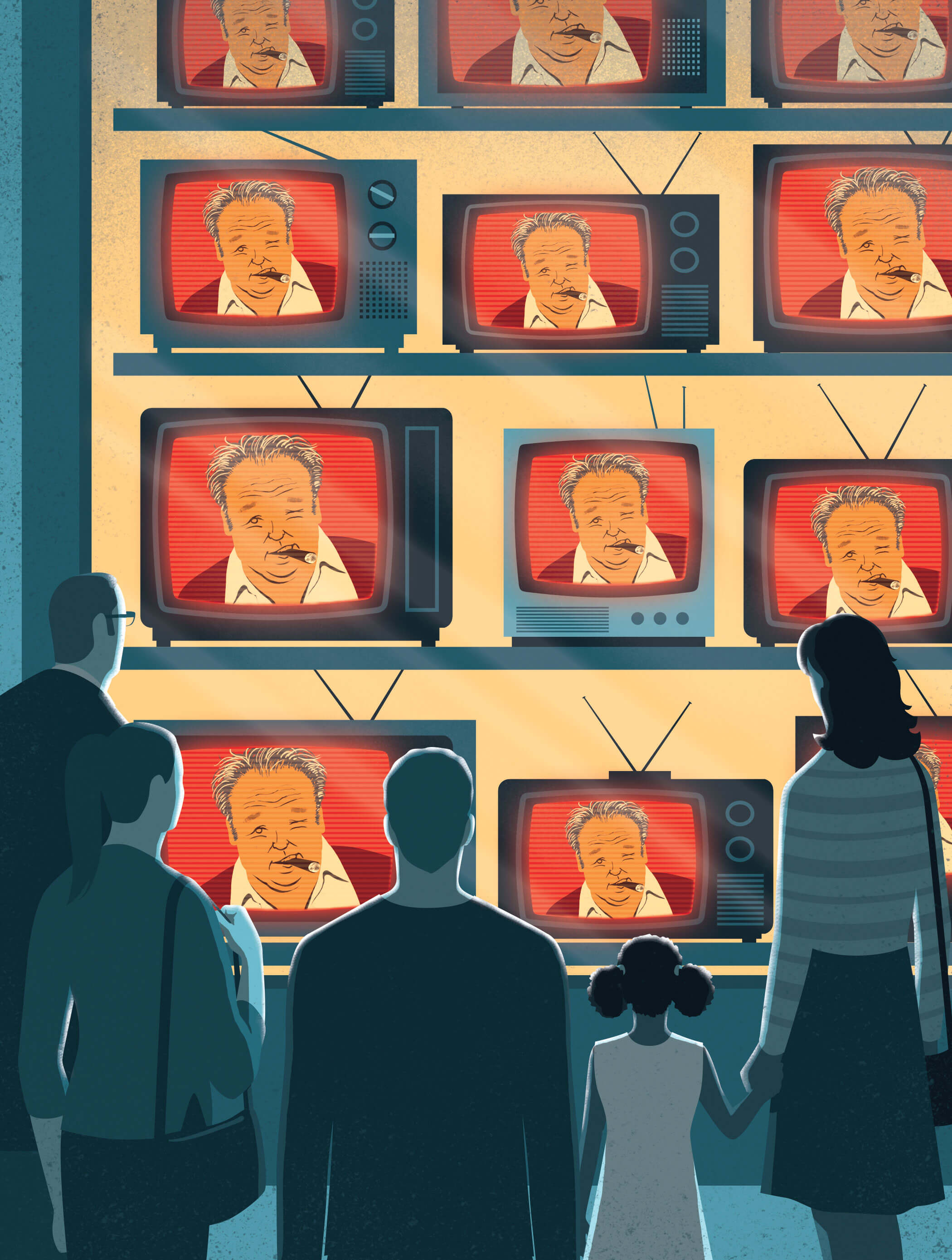

L. Benjamin Rolsky’s new book documents the spiritual politics of television producer Norman Lear and the Religious Left.

The Rise and Fall of the Religious Left, the first book from L. Benjamin Rolsky, illuminates our current political moment by examining famed television producer Norman Lear’s career as an example of liberal religious mobilization in opposition to the rise of the Religious Right in the public sphere in the 1970s. We asked Rolsky, an adjunct professor in Monmouth’s Department of History and Anthropology, about his research and reflections on these “Culture Wars,” and how he plans to continue his scholarship in that area.

What’s the “elevator pitch” for your book?

This is a story about the Religious Left[1], which is in the news all over the place these days— you watch any kind of Democratic debate and it’ll come up. But it’s really the story of Norman Lear and his career in media from All in the Family to his nonprofit organization, People for the American Way[2].

The book uses Lear as a case study for a broader understanding of politics: a progressive, civically minded vision of the public square that says, “We don’t put a bigot on TV because we agree with the bigot; we put a bigot on TV because he’s going to put a mirror up to the rest of us so we can theoretically become better citizens.”

How was a sitcom like All in the Family supposed to accomplish something like that?

Archie Bunker[3]is a poster child for what happened politically during the early 1970s. He’s someone who grew up during the Great Depression and the New Deal. He supported Democrats at one point because they were about labor and working class issues. But then you have conservatives coming along who are very good at getting the idea out there that someone like Archie has more to fear from minorities than he does from anyone else.

The liberal religious approach to societal change is to tweak the structures of society so that individuals will then act accordingly, whereas the conservative approach is to change the heart in order to change society. So the assumption with All in the Family is that the audience will see Archie Bunker and understand that it’s satire. Lear’s programming isn’t going to tell you what to think. It’ll give you the viewpoints; it’ll give you the conversation.

Lear represents the pinnacle of that type of cultural influence and power. All in the Family was on at a time when there were only three networks, so hundreds of millions of people a week could watch the show.

Did Lear’s approach to politics and societal change actually work?

I think it’s a very ambivalent legacy. My argument is that when Democrats started reaching out to minority communities of various sorts, Republicans said, “OK, we’re going to bring over the Archie Bunkers of the world, we’re going to double down on those people for the foreseeable future.”

I think the biggest naïveté of Lear and the Religious Left was that if you put the right stuff in front of people, then they’ll make the best choices. Take All in the Family as an example: You put the bigot in front of people and you assume that they won’t be as racist over time. That was the perspective of Carroll O’Connor, the actor who played Archie Bunker. He said that Archie is really meant for the dustbin of history.

But then you’re kind of leaving behind a group of people who are going to feel ignored, and they’re going to feel condescended to—right up until the conservative advertisement that says, “Are you worried about the person of color that’s going to take your job? Then vote for us; we’re going to make sure that doesn’t happen.”

And the Religious Left of the time wasn’t necessarily a coalition, or even a movement, because it wasn’t that well organized. It wasn’t pragmatic, it was aspirational. It wasn’t like the fine-tuned campaigns of the Religious Right[4],which only invested time, money, and campaigning when the return on investment was going to be appropriate.

We don’t put a bigot on TV because we agree with the bigot; we put a bigot on TV because he’s going to put a mirror up to the rest of us so we can theoretically become better citizens.

So despite Norman Lear’s domination of TV programming in the 1970s, you say that the Religious Left still experienced a significant fall. Why?

People usually talk about this period as the “Culture Wars.” It’s that period of time since the 1960s when we stopped arguing about things like gross domestic product and started arguing about who people should sleep with. Politics since the 1960s became about hot-button social issues. I think that helped the Religious Left when it was about civil rights, but I think it hurt them when it came to abortion.

When you make a movement about civil rights, you’re reducing very broad traditions—like Judaism or Christianity—down to particular issues of importance. But that way of mobilizing for something like civil rights, with explicitly moral, Christian language, then allows the rights of the unborn to become a moral, theological issue, too. Who gets to decide what those issues of importance are going to be? In one moment, it’s going to be civil rights, and in another it’s going to be the unborn fetus.

Single-issue politics might be good if you are in favor of the issue—whether it’s civil rights or gay marriage—but I don’t think that reducing everything down to these things helped progressives at all. I think if anything it turned politics into marketing and market research. Religious conservatives came up with things like Bible Scorecards[5] in the 1970s to help citizens understand and judge the politicians based on how they answered questions about certain theological issues. The Religious Right has a certain understanding of how to be political, an understanding of how to mobilize people. For them, politics is not about widening the circle and bringing in a diversity of people, it’s about winning.

Another part of the fall is that religious liberals have become too comfortable with turning on something like The Colbert Report and thinking that was their political act for the day. I think they’ve gotten comfortable with a certain type of cultural influence that didn’t necessarily translate into the day-to-day mobilization and activism that you need to actually make things happen.

So what should those who consider themselves to be on the Religious Left do today?

Those who ascribe to or identify with the Religious Left have to do a little self-examination. I think a simple suggestion would be to start talking to the Archie Bunkers again. We’ve ignored them for a very long time, and in many ways they’ve come back with a vengeance—and we wonder why.

Part of the reason is, we’ve been distracted by the racist things they’ve said. Racism is obviously something that we should be concerned with; but at the same time, Archie Bunker’s paycheck was dwindling. He was also suffering under the conditions that led to the death of the working class.

If you want anything to change, you’re going to have to think about how you engage in politics a little bit more pragmatically. You can’t just assume that with something like immigration, for example, people are going to come up with the best decision.

What’s next for your scholarship?

I have a tentative title for my next book: Establishments and Their Fall: Direct Mail, the New Right, and the Remaking of American Politics. E.J. Dionne wrote a book[6] about how the Republican Party has tried to purify itself since Barry Goldwater—purifying in the sense that they’ve gotten rid of the most moderate dimensions of the party. My contribution to that conversation would be an analysis of the forms of communication and technology that were used to make that purification possible.

How did Republican PR people learn from Barry Goldwater’s failed campaigns? How did the New Right strategists in the 1970s deploy and use the mailing lists of Goldwater to connect people in a way that they had never been connected before? What if direct mail starts to reach these people in their mailboxes and they then know they’re not alone? That the Religious Right will defend their Christian values to the hilt?

Direct mail was a way of bringing people together in a relatively inexpensive way that gave them a sense of identity, that let them know they were part of something bigger. How are you going to get that housewife from suburbia to get off her couch? You’re going to tell her that there are people moving into her neighborhood; you’re going to tell her that what people do in the privacy of their own homes affects everyone, right? That’s the brilliance of conservative argumentation.

Footnotes

1. LBR: The Religious Left is an understanding of religion and its sacred texts that speaks to social concerns, rather than having some sort of “born-again” conversion experience. We can talk about the Religious Left as part of American religious liberalism, a broader tradition that includes Walt Whitman, Emerson and Thoreau, etc. Lear’s career in media is representative of a Religious Left understanding of American religion and politics from outside the confines of traditionally institutional settings such as churches or synagogues.

2. People for the American Way is an advocacy group founded by Lear in 1980 to educate by combating the seemingly invasive media-savvy agenda of the newly formed Christian Right.

3. The patriarch of the 1970s sitcom All in the Family was a bluntly bigoted WWII veteran and warehouse dock worker who drove a taxi for extra income and lived in a row house with his family in Queens, New York. He was portrayed as being stubborn with his adult daughter, Gloria; argumentative with his liberal son-in-law, Mike, whom he dubbed “Meathead”; and dismissive and condescending toward his deferential wife, Edith.

4. The terms “Religious Right,” “Christian Right,” and “New Christian Right” are largely interchangeable, and can be understood both as a collection of organizations, groups, and individuals who organized on a grassroots level, and as shorthand for a group of people led not only by televangelists but also by savvy political advisers. The “New Right” describes a conservative political movement between 1955 and 1964 that centered around right-wing libertarians, traditionalists, and anti-communists at William F. Buckley’s National Review.

5. The Bible Scorecard, sometimes referred to as a Biblical Scorecard, was a direct mail questionnaire authored by Evangelical pastor Jerry Falwell and other members of the Religious Right in the late 1970s to mobilize previously inactive Christians in American presidential elections. The questionnaire scored all the candidates on the purported moral issues of the election (e.g., abortion, homosexuality, and national defense).

6. Why the Right Went Wrong: Conservatism—From Goldwater to Trump and Beyond. E.J. Dionne is an American journalist, political commentator, and frequent op-ed columnist for The Washington Post.