A black and white looping video without audio that is a closeup of waves on the ocean. The words Catching Ghosts is overlaid. This serves as the page title.

Catching Ghosts

On the hunt with Monmouth faculty and students working to stop a stealthy killer that’s decimating the Barnegat Bay ecosystem.

Seven feet below the surface of Barnegat Bay, burrowed in the thick mud that coats the waterway’s floor, sits a predator the size of a sea turtle. Hidden by sediment and organisms encrusted along its surface, it blends into the murky surroundings and waits, mouth agape, to trap unsuspecting marine life in its unyielding grip.

But this predator is no creature. It’s one of hundreds of derelict crab pots that coat the bottom of the bay. Considered marine debris, the traps are abandoned—a sometimes intentional, sometimes accidental byproduct of commercial and recreational fishing that is having a devastating impact on this aquatic ecosystem.

“Derelict fishing gear can cause the death of a variety of marine organisms, cause economic loss to the fishing industry, and pose threats to human health,” says Emily Heiser, a wildlife biologist with the Conserve Wildlife Foundation of New Jersey. Of particular concern to ecologists is the danger these abandoned pots pose to northern diamondback terrapins—a small, native turtle that is considered a species of special concern in New Jersey.

The diamondback terrapins sometimes enter crab pots because there’s a food source inside, such as leftover bait or blue crabs themselves, says Heiser. Many commercial crab pots have by-catch reduction devices (which minimizes the amount of marine life that become unintentionally trapped) and degradable latch connectors designed to wear away over time. But those mechanisms do not always function properly, and as a result, terrapins and fish species often become trapped. “Once the terrapins become trapped in the pots, they can easily drown,” Heiser says. “We pulled up one pot that had over 11 dead terrapins.”

The derelict pots also get intermittently swept along the bay floor by strong currents and choppy storm waters and can cause serious damage to boat propellers or the hulls of vessels that run into them.

In some states, as many as 30 percent of the crab pots dropped into the water remain unaccounted for, but it is unknown how many are lost each year in New Jersey, says Heiser. So two years ago, CWF partnered with Monmouth University, Stockton University, and the Marine Academy of Technology and Environmental Science on a project to assess how widespread the problem is and, at the same time, remove as many derelict pots as possible from the bay.

In The Bay

“The term ‘ghost fishing’ is used a lot,” says Jim Nickels, a marine scientist at Monmouth’s Urban Coast Institute, regarding instances when gear such as crab pots are lost but continue to catch marine life.

Nickels, who also teaches classes in Monmouth’s biology department, supervised the university’s involvement with the project. During the past two years, he and a team of student volunteers made more than a dozen trips aboard the UCI’s 27-foot research vessel, Seahawk, traversing the northern portion of Barnegat Bay—from Good Luck Point in Berkeley Township, New Jersey, up to the base of the canal near Bay Head, New Jersey—searching for and retrieving derelict pots. Their work had to revolve around the closure of the commercial crabbing season so as to not disrupt the industry, which meant Nickels and his students could only go out on the water between December 1 and March 15.

“[It’s] a lovely time of year… long, cold, miserable days,” jokes Nickels light-heartedly and somewhat sarcastically. “But it gives [students] a chance to really see what day-in and day-out survey operations are like.”

Each expedition followed a one-two pattern: one trip focused primarily on finding the pots using high-tech equipment onboard the vessel, and a follow-up trip, made on a separate day, focused on physically grappling for the pots hidden below the surface.

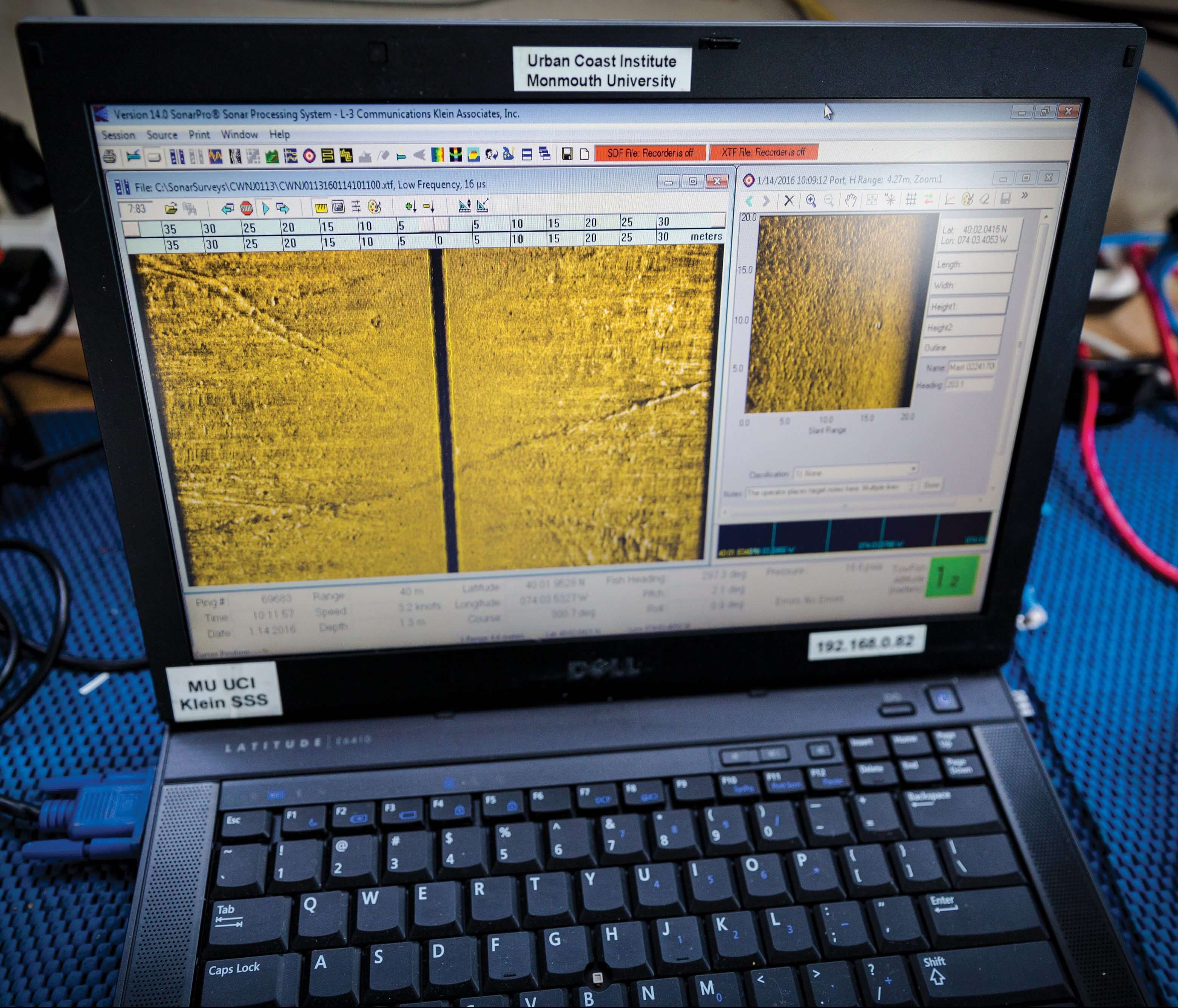

The task of finding the pots was done with side-scan SONAR—a three-foot-long, torpedo-like piece of equipment, called a fish, which costs about $35,000. Students would launch the SONAR equipment overboard, where it sat about two feet below the waterline. Nickels would then typically maintain a steady speed of 5 mph as the instrument was towed below the surface, taking images in real time.

“It’s like two flashlights shining out sideways, so anything that is on or above the bottom, it sees and illuminates,” says Nickels of the side-scan SONAR.

Those images were transported via a long blue cable to three onboard computers. It was the students’ job, for hours on end, to watch the computer monitors and essentially take screenshots of anything that resembled a crab trap sitting below. Nickels would then sit with Marc Molé, a marine and environmental biology and policy major, who worked as a research assistant on the project both years, and together they would scan the images looking for rectangular blotches on the sheet—indicative of a pot. Using GPS coordinates that were captured with each screenshot, the Monmouth team could then make a second trip to retrieve the pots.

Along with the more than 600 derelict pots they identified during the past two winters, Molé says the Monmouth team found a plethora of other debris: tires, cables, propellers, an old anchor—even a capsized boat that hadn’t been recorded on any naval charts. It angered the students, many of whom plan to pursue careers studying marine life.

“It’s not so much the crab pots really, but the tires and electric cables—they’re what really get to me,” says Molé. “The solution to pollution is dilution—it’s what people used to think.”

Those pots are worth a lot of money to them, and they don’t want to lose as much as they can help—and it just [helps by] being good citizens and neighbors to everyone else.

Two winters ago, when Nickels and his students were physically pulling up pots themselves, they retrieved about 25 traps—no easy feat. Covered in mud and encrusted with various organisms, the pots are filthy, foul-smelling, and unwieldy.

“I remember the first time I was jumping around like, ‘We’ve got one!’” says Kylie Johnson, who was involved on the project during both seasons and was on the boat one day in February 2016 when the team recovered a string of 10 pots, which took them about 40 minutes to retrieve in the freezing conditions. “We saw one, and we’re like, ‘Let’s go for it.’ Then it was attached to nine others, and that’s what made it really hard. We thought it was maybe tied down, but it was just being held down by the weight of the other nine.”

According to Nickels, commercial crabbers often attach pots together, making them easier to retrieve with the day’s catch. But if the pot connected to the buoy becomes detached, it can be hard to find any of the traps—especially for crabbers who are often without their own side-scan SONAR equipment on board.

As a way of retrieving more pots, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, one of the project funders, gave basic side-scan equipment to commercial crabbers who offered to help in the retrieval process. Nickels says that was a big help: It allowed the teams to retrieve twice as many pots in the second year and was a great incentive for the local crabbers.

“We actually worked very closely with several commercial crabbers because, obviously, it’s in their best interest too,” says Nickels. “Those pots are worth a lot of money to them, and they don’t want to lose as much as they can help—and it just [helps by] being good citizens and neighbors to everyone else.”

Throughout the process, the commercial pots that were retrieved with their tags still attached were processed by students from MATES and Stockton and then returned to the crabbers. Untagged traps and recreational pots were sent to Covanta, a waste management company, for recycling.

Molé, who landed a job working with the NY/NJ Baykeeper prior to graduating this past May, says it was a great experience to connect with people from various schools and organizations who all shared the same end goal.

“So many people have come together, and you don’t often see the commercial fishermen actually working with the people doing the research—they don’t tend to like us too much because we just like to put regulations on things basically,” says Molé. Working with the MATES students, who processed the pots, was also rewarding, he says. “It’s cool to help teach the next generation to do this type of stuff.”

Both Johnson and Molé say that it’s experiences like this—and the connections that faculty like Nickels have—that make all of the difference when it comes to being prepared for life after Monmouth.

“A lot of what we’ve learned is that you have to get your foot in the door using some project where you get involved with an organization, and it’s a networking process,” says Johnson. “And as an undergraduate, it’s good to participate in different research projects to get experience. … Because [Professor Nickels] can tell you how a boat works, but it’s not until you’re out on a boat that you understand.”

Impact and Experience

All told, Nickels says 1,274 pots were targeted and collected during the past two years. That amount of debris could fill twelve 30-cubic-yard dumpsters with a potential weight of 60 tons, he estimated.

Heiser says the data collected during the project will be cross-checked with data collected from two similar projects happening in New Jersey—one headed up by New Jersey Audubon that focuses on pots in the Delaware Bay and one headed up by Stockton University that focuses on pots in the southern reaches of Barnegat Bay and Great Bay.

Nickels, who enjoyed working on the project, says all of the students involved expressed their appreciation for the real-world experience that it provided.

“They’ve all enjoyed it because it is a little bit of a different experience, and it’s a really neat project because it does have a true outcome to it,” he says. “And that’s important, so they can take some pride and knowledge that they worked on something that mattered.”