Bigger Than Themselves

Beatles expert Kenneth Womack explains why the Fab Four still fascinate us.

Beatlemania will descend on campus in November courtesy of a four-day international symposium marking the 50th anniversary of the band’s landmark LP The Beatles (aka The White Album). We asked Monmouth’s own Kenneth Womack, a world-renowned authority on the Beatles, why the Fab Four are still the band everyone aspires to top.

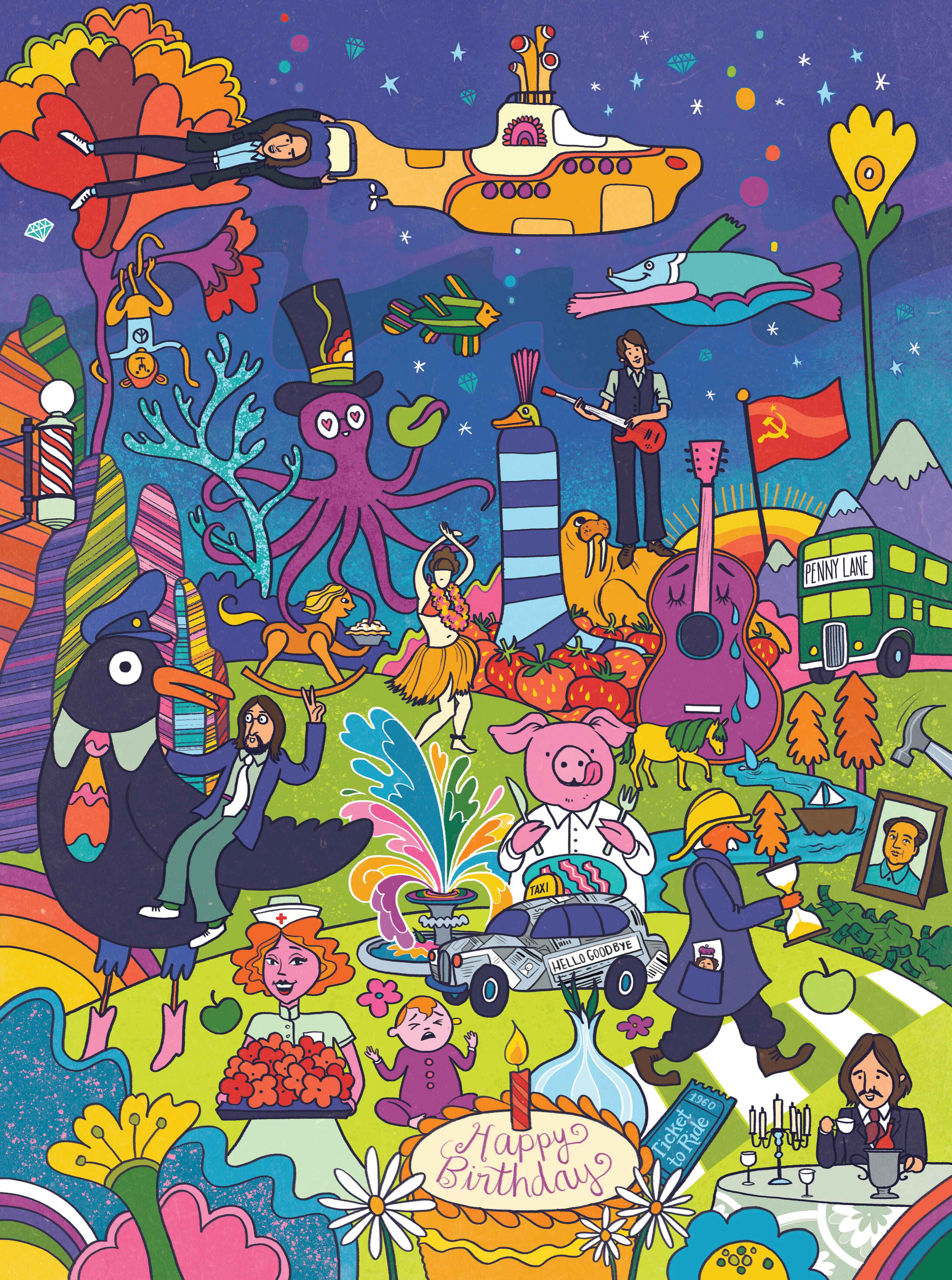

- Abbey Road (the stripes under the fireman with an hourglass)

- Apples (sprinkled throughout, in reference to the band’s record label)

- “Back in the U.S.S.R.” (multiple references: the flag and the snow-peaked mountains)

- “Birthday” (cake with candle)

- “Blackbird” (wearing a tie and carrying John)

- “Cry Baby Cry” (next to the cake)

- “Dig a Pony” (the small horse alongside the river)

- “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except Me and My Monkey” (the monkey hanging from the tree)

- “Glass Onion” (next to the cake)

- “Hello, Goodbye” (multiple references: the song title is the headline on the newspaper taxi, and the hula dancer is a nod to the promotional videos the band made for the song)

- “Here Comes the Sun” (rising behind the mountains; we’ll also take “Sun King”)

- “I Am the Walrus” (underneath Paul)

- “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” (multiple references: the boat on a river, cellophane flowers of yellow and green, flowers growing incredibly high, a rocking horse with a marshmallow pie, a newspaper taxi, and diamonds in the sky)

- “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” (above the picture frame on the right)

- “Money” (a pile of it underneath the picture frame)

- “Octopus’s Garden” (that top hat–wearing purple cephalopod)

- “Penny Lane” (multiple references: the bus’s destination sign, the barber pole, the fireman with an hourglass with a portrait of the Queen in his pocket, and a pretty nurse selling poppies from a tray; plus, Ringo’s table setting is a nod to the song’s video)

- “Piggies” (just as George described, in a starched white shirt clutching a fork and knife and eating bacon)

- “Revolution 1” (Chairman Mao photo)

- “Strawberry Fields Forever” (underneath the walrus)

- “Ticket to Ride” (next to the cake)

- “While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (above the pony)

- “Yellow Submarine” (multiple references: the sub; much of the background imagery is reminiscent of the song’s video; and the blackbird’s hat is a nod to Old Fred, the captain in the film Yellow Submarine)

How and when did you become a Beatles fan?

It was 1977, and my favorite morning television program[1] was replaced with The Beatles Cartoons [2]. It’s kind of a lame discovery story because the cartoons weren’t voiced by the Beatles. They were just these little sing-alongs, and each featured a nonsensical plot with fake Beatle voices where they would act cool in that fashion, and do a couple of songs. But I’d never heard songs like that before. When you hear the Beatles, there is something instantly different about them. They don’t sound like the ’60s. They sound like really well-crafted songs.

So my father went to the Houston Public Library and picked up all the Beatles books they had. Most of them were silly art books with paintings that depicted the lyrics. But he brought them home and I went from there.

So an obsession was born?

I suppose, though you used the word fan before. I’ve never really been a fan in the sense that I don’t collect [Beatles memorabilia]. It’s always been about the music.

What interests you about them as a researcher and an academic?

Their story is fascinating. How does this band in seven years [3] move so quickly through all of these different musical, generic changes, and then disappear and leave the stage forever, and leave it on such a high note, having achieved a swan song like the Abbey Road LP? It’s remarkable. James Joyce and Picasso didn’t have careers like that, with such an intense period of ever-increasing quality and artistic growth. Pink Floyd and the Rolling Stones didn’t. It’s unique in music and art.

Why do you think the Beatles were able to do it?

I think it has very much to do with their lives. They were working-class kids when they started this project in Liverpool, and may not have had many of the privileges—but they knew how to work hard. These are guys who had everything in the world by the time they were roughly 22 to 24 years old, and yet they still persisted. They still wanted to take their music and their ideas places. That’s exciting to me, and it’s a great story for our students [4].

That self-consciousness is why the Beatles are no different from Picasso or Joyce. They aren’t just trying to, as Paul once said, “write a song and get a swimming pool.” They’re thinking, “This is for all time.” There’s a certain point where they begin to think, “What we’re doing here is bigger than us.” That’s probably why they’re still in the studio trying to make the Abbey Road record in the summer of 1969 [5]. They know it’s bigger than they are.

You mention they didn’t record together for long. How and why were they able to have such an impact in their time?

One important factor was they very smartly got off the road [6] in August 1966. That was easily the most important move they made after hooking up with Brian Epstein and George Martin.

Another factor was that in 1964 alone there were three different television specials devoted to the “genius of Lennon and McCartney.” I would argue that raised the stakes of authorship in art very high inside the band, and it told them, “You’re doing something important.”

And as my friend and fellow Beatles author Steve Turner says, there was an arms race that developed. As the ’60s wore on a lot of good bands were suddenly in vogue. You’ve got the Stones finding their feet in 1965. You’ve got The Who. You’ve got The Kinks. You have great American acts like the Beach Boys. And suddenly—it’s not that the Beatles felt challenged, but they wanted to stay ahead of the pack, and that has a lot to do with them moving forward too. They didn’t want to produce the same sound with every album. They were very conscious about that.

And why has that influence endured?

Two reasons. One is George Martin [7]. He was absolutely impeccable about ensuring their music was recorded with the highest possible quality, so when you hear the Beatles, there are very few songs you hear today and think, “Wow, that sounds like a record recorded in 1963.” Most of their records have good punch and freshness to them; there’s a certain live sound to them. George worked painstakingly to ensure their recordings had that kind of lasting power.

Part two is really part one in the sense that they’re great songs. It’s good composition, great songwriting. That’s why in that moment in 1977 [when I first heard them] I heard something different. I believe the song was “Help!” and when you think about it, that song is rife with little fascinating touches. It has descending bass lines. It has a very difficult arpeggiated guitar part. It has that driving drum sound. Great lyrics. There’s even a part where the instruments drop away and it’s just the acoustic guitar and Lennon singing. All of this and the song is, what—two minutes? That’s what makes them great, right there.

But there are a lot of great bands. Why are people still studying the Beatles and their music? Why, for example, are people coming from around the world for a conference [8] on The White Album 50 years after it was released?

There are many factors, but again it comes down to creating great material and being able to sustain it at a certain level.

And there’s a high versus low culture argument at a certain point. Think of James Joyce. He is undeniably high culture: a high-minded writer whose books—A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, Ulysses—are challenging works that force us to learn a new language, or a new way of reading at least, but are not easily consumable. Then you’ve got Robert Ludlum, who can mesmerize you with a spy tale and draw you in with a page-turner. We teach courses on James Joyce. We’re not teaching Robert Ludlum.

The Beatles were the high culture of their genre. They eclipsed their genre. And The White Album—it’s not a perfect record. It’s a sort of warts-and-all kind of thing, but they were trying to do something big with it [9]. It was designed to be the kind of art object that says, “Study me,” in the same way that you open up Ulysses and it says, “Study me.”

How so?

They crafted those songs. They wrote them in India where they went to become enlightened, and they were living in huts and going to lectures—who does that at the height of their fame, when they can be doing anything else that they want?

Then they come back, make these demos [10], and begin spending more time on these songs than they did making Sgt. Pepper. And the coup de grâce is at the end. They have a 24-hour mixing and sequencing session with George Martin, where they sequence every song and they make choices about how it goes from “Back in the USSR” to a song called “Good Night.” They very carefully made artistic choices all the way through, often so that you experience a kind of whiplash as it goes from one style to a completely different one.

With all of that going on, what will the symposium focus on?

There’s something for everybody. There’ll be academic paper presentations, sure, but we’ll also have musical performances. We’ll have a music demonstration room with guitars, pianos, and drums where people will show you how the Beatles did what they did, and how sounds were discovered accidentally. We’re going to have a recording demonstration room where you can mix a track yourself and take the MP3 home. We’ll have a lot of important Beatles authors, including Mark Lewisohn and Rob Sheffield. Chris Thomas, who stepped in for George during The White Album sessions, will be here. People will have a chance to meet and talk with them. That’s pretty rare.

Last question. Do you think any band can ever again have the decades-spanning influence the Beatles have enjoyed?

I want it to happen, very badly. I want to hear a band that is working at that kind of innovative, world-breaking level. I’m ready for the next pop explosion. I want to hear it. I want to be blown away by it, to be transfixed. Don’t you?

Liner Notes

- KW: “New Zoo Revue, which, looking back, was kind of a goofy show but I can’t speak to 11-year-old me about it.”

- The animated television show originally ran on ABC in the 1960s.

- KW: “Their first session with George is June 1962, and the last session with all four Beatles present was August 1969.”

- Womack is teaching “The Evolving Artistry of the Beatles” this semester. Among other things, students explore how the band “begins with songs like ‘Love Me Do’ … and ends with the powerful symphonic suite that is the Abbey Road medley. That’s a long road to go in such a short period,” says Womack.

- KW: “There are debates on how certain [the Beatles] were that it was over, but nothing changes the fact that they had to foist themselves back together for one last stab at greatness.”

- KW: “They could only do that because they were the most privileged creative act in the world and they didn’t need to go on the road to make money.”

- Womack is the author of Maximum Volume: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin (The Early Years, 1926–1966) and Sound Pictures: The Life of Beatles Producer George Martin (The Later Years, 1966–2016).

- The Beatles’ The White Album: An International Symposium will be held Nov. 8–11 at Monmouth University. Info at monmouth.edu/the-white-album

- KW: “I like how Paul McCartney speaks about it as ‘The Beatles’ White Album.’ It’s as if the LP has eclipsed the bandmates. His famous line is ‘It’s great. It sold. It’s the bloody Beatles’ White Album. Shut up!’”

- The so-called Esher tapes were “blueprints” for what would become The White Album, says Womack. Award-winning Beatles author Robert Rodriguez will lead a panel discussion of the tapes during Monmouth’s symposium.

Kenneth Womack is dean of the Wayne D. McMurray School of Humanities and Social Sciences at Monmouth University.