A True Original

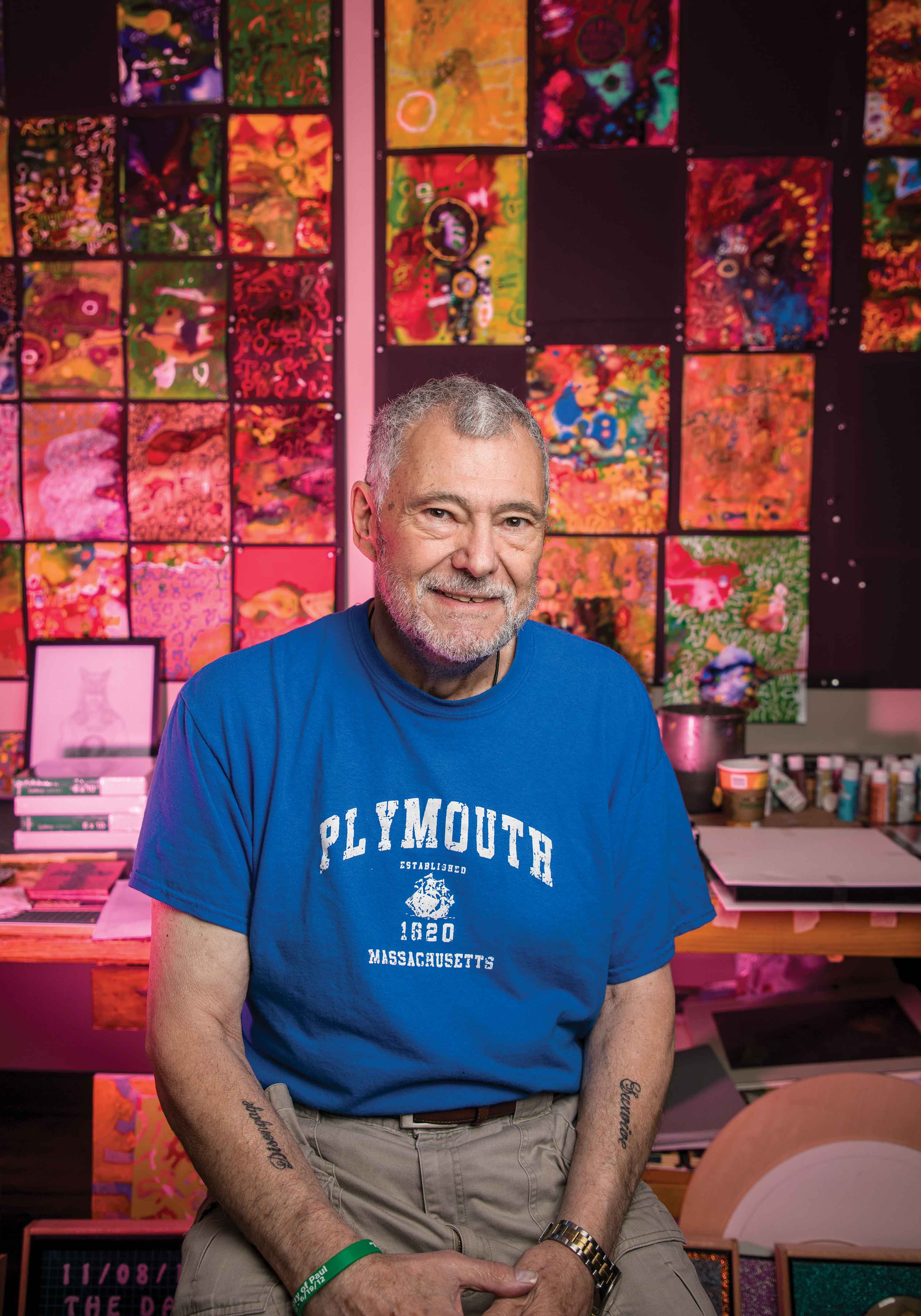

Professor Vincent DiMattio has been practicing what he teaches for half a century.

Almost every day for the last 50 years, Professor Vincent DiMattio has gone into his art studio at Monmouth and made something. It may be a painting or a sculpture, a drawing or a collage. It could be playful or mysterious, sensual or haunting. Some days it may be only a few brushstrokes, others a near-finished piece. But week after week, year after year, DiMattio is there, putting the techniques that he’s taught at Monmouth for the last five decades into practice himself.

“I’ll give it to you in one word: compulsion,” says DiMattio. “I have no choice—I just have to keep making things. I think I’ll have a sketch pad with me on my deathbed.”

Whether it’s discipline, devotion, or, as he says, compulsion, his daily practice has resulted in a massive body of work. This semester, Monmouth is celebrating that work—and the artist behind it—with a retrospective exhibition. From now through Dec. 7, roughly 500 pieces that DiMattio made during his 50 years at Monmouth are on view in three campus galleries, including the one named in his honor.

“His work is simply astonishing,” says Robert Rechnitz, professor emeritus of English, a longtime friend of DiMattio. “It’s deeply moving and profoundly original. I don’t know of anybody who works like he does—and there is so much of it.”

Rechnitz’s wife, Joan ’84, ’12HN, who has taken several courses with DiMattio, says she is particularly drawn to his sense of color. “They just look so beautiful together,” she says. “Some are unexpected, and sometimes they almost vibrate in a very beautiful way.”

DiMattio started making art as a kid in Quincy, Massachusetts, but he never thought it could become a career. He had finished high school and was playing American Legion Baseball when a friend invited him to tag along on a visit to Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston. “I was astounded,” DiMattio remembers. “This was a place where kids could actually scribble and make things—I didn’t even know these art schools existed.” He put together a portfolio, submitted it, and was soon an incoming freshman at MassArt.

I think it’s important for artists to be productive. This business of waiting for an idea—that’s a lot of crap. It’s better that you do something, even if it isn’t successful, that you can look at and learn from.

After an MFA from Southern Illinois University and a couple of years teaching at the University of Wisconsin, DiMattio arrived at Monmouth in 1968—the height of Vietnam War protests. Although he’d been hired to teach undergraduates about composition and color, he often found himself managing them outside the classroom, too.

“I’m out with a megaphone trying to keep students off the street so that state troopers won’t beat them over the head with clubs,” he remembers of an especially eventful night. It was a new but not uncomfortable role for DiMattio, who had marched with Martin Luther King Jr. in Milwaukee and whose baby son was, according to DiMattio, the youngest member of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee in the country.

“Vince was high-spirited, exploding with energy, wary of authority, and absorbed in his work,” recalls Kenneth Stunkel, professor emeritus of history and a former dean of Monmouth, who still calls DiMattio a close friend. And from the time they met, it was obvious: “He was driven from within to create,” says Stunkel.

Soon after he arrived at Monmouth, DiMattio channeled some of that drive into giving the University its first art gallery. He found a small room on campus and helped transform it into a showcase for student and faculty work. Eventually the gallery moved into a larger space, with DiMattio still overseeing it—on top of his other responsibilities. “At one time, I taught an overload, I was chair of the department, and I ran the gallery,” he says. “That’s kind of unheard of.”

Still, he kept making time for those daily studio visits. “I think it’s important for artists to be productive,” he says. “This business of waiting for an idea—that’s a lot of crap. It’s better that you do something, even if it isn’t successful, that you can look at and learn from.”

The pieces on view in his 50-year retrospective are proof not only of DiMattio’s dedication and productivity, but also the range of his work. “There are so many beginnings,” says Bob Rechnitz. “He does not create the same things over and over. As a matter of fact, he seems constantly to be realizing new visions. And of course that’s one of the appeals: How did you come up with this? How did you dream up that?”

Phil Imbriano ’15, who took three of DiMattio’s courses, says DiMattio often invited students into his studio, which sits beside his classroom. “He’d always show us what he was working on, and that passion rubbed off on me for sure,” Imbriano says. “When I’d see his work, it inspired me.”

The two are still close friends, but Imbriano admits that it wasn’t an instant connection. At first he struggled with his new instructor’s blunt critiques and difficult assignments. But as his own technique improved, he started to see the value in DiMattio’s approach. He still remembers DiMattio telling the class that artists “don’t go out every weekend to party; they stay in and work.” It’s a message that echoes in his head today—and that keeps him committed to making his own work, even with a full-time job in graphic design.

Imbriano is also one of several hundred students who have wandered through famous museums and explored new cities alongside DiMattio. After a sabbatical in Madrid for the full 1979–80 academic year, DiMattio came back to campus eager to give students a taste of his life-changing experience. Two years later, he led his first “Art in…” trip during spring break. He’s now taken classes to Europe 20 times—most recently, Berlin in 2017.

In 2013, DiMattio’s 45th year at Monmouth, a two-story art gallery in the new Joan and Robert Rechnitz Hall was dedicated as the DiMattio Gallery. He admits that the gesture brought him to tears. Now five years later, he’s embracing another Monmouth milestone.

“Monmouth University is special in so many ways and I am so damn lucky to have spent 50 years on this campus,” he says. “I’ve been through a lot, the school has been through a lot, and we have both survived. I’m very lucky to be here and to have been here.”

State of The Art

Although DiMattio insists that “if I could explain everything about my work, then it’s time to give it up,” he walked us through the inspiration and process behind several of his series.

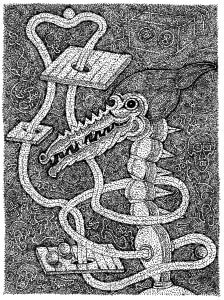

“I used to have these nightmares—one almost every night. Then I started making these drawings. I’d use the method of stippling—a lot of little dots. I’d fill the page with that and then look at those dots and find all of these creatures and strange people. I made about 60 pieces—pen and ink, directly on paper—that had to do with the dream series. It let out a lot of frustrations I was feeling.”

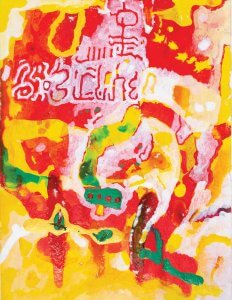

“I’ve always been in love with the written word—with letters. I’ve invented my own kind of calligraphy. They’re invented forms and the messages have to be felt, not seen. People will come up to me and say, what does this say? I tell them that it says what you feel when you’re looking at it. Of course, they have trouble understanding that sometimes. But invention is so damn important to an artist. I love ceremony, I love magic. The letters relate to a lot of that.”

“There’s a real history of artists who’ve shown interest in assemblages and using things that society has pretty much cast aside. That interested me. I’d pick things up off the street when I was in Europe. I’d buy old magazines. Then I’d start to play with these things in the studio, not knowing in advance what they were going to look like. They’re very spontaneous.”