A New School of Thought

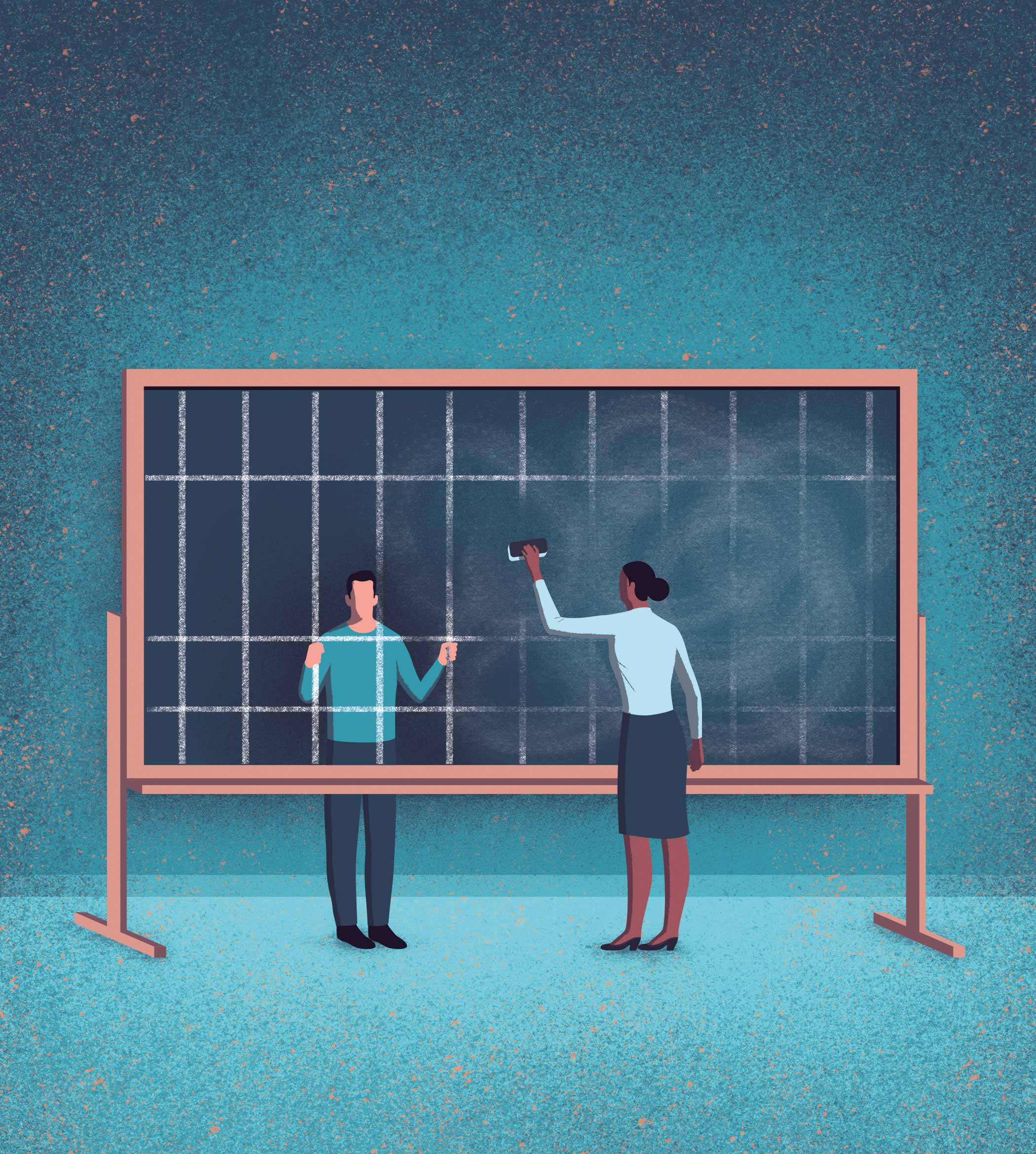

America’s school-to-prison pipeline is having a devastating effect on at-risk youth. Monmouth students have a plan to fix the system.

“When I grow up, I want to be a criminal.” It’s a statement no child is likely to ever make, said senior Lacey Wood to those in attendance at the Reverse the Flow! Stop Criminalizing Our Youth forum, held on campus last November.

The event featured presentations by eight Monmouth students who completed a special course, Investigating the School-to-Prison Pipeline. Over the span of two semesters, Wood and her classmates examined a disturbing trend: Minority youth in this country are being disproportionately funneled from school systems into prison systems, which in turn, can lead to a lifetime of recidivism for them.

As part of the course, the students studied how school systems are failing to support large segments of the population, a problem that often falls along racial lines. They also traveled inside New Jersey State Prison (NJSP) to learn about the pipeline from those who have experienced it firsthand.

Working in tandem with 11 incarcerated men from NJSP, the Monmouth students developed a plan of action for shutting down the pipeline, reducing recidivism rates, and countering the stigma associated with ex-convicts in an effort to help them assimilate back into society. At the forum in November, the Monmouth students presented their work to a packed room.

“When we were children … we dreamt of growing up to be astronauts, doctors, police officers, firefighters—professions that seemed noble in our young eyes,” Wood told the audience that day. “So how did 2.3 million children with dreams of becoming the central members of society end up as adults living a nightmare of an existence behind bars?”

Pipeline Origins

To understand how such a system came into existence, one must look back at least as far as the 1990s when, in response to concerns over the growth of violent incidents in schools, Congress passed the Gun-Free Schools Act of 1994. The law required every state receiving federal funding for elementary and secondary education to adopt zero-tolerance policies in regard to violent behavior. One of the edicts of the law required states to expel, for a minimum of one year, any student who brought a gun to school (though administrators could review incidents on a case-by-case basis).

As states adopted their own policies, many cast a wide net under which minor infractions, like calling out in class, could be counted as equal to major infractions, such as bringing a weapon to school. Critics have long argued that the policies are vague and arbitrarily enforced and have done little to curb violence in school settings during the past two decades. What the policies did do, they say, was create prison-like environments in schools, often making it easier for districts to punish and eliminate children with problems rather than help them.

“[The policies] allow school officials to ditch their evaluation of student behavior and to enact more suspensions and expulsions for the smallest infractions,” senior Erica Bogert said during the forum. Especially vulnerable under these policies are students of color, particularly those with disabilities, and at-risk youth, including those with histories of poverty, abuse, or neglect who attend school in poorly funded districts with limited resources. To illustrate her point, Bogert shared the story of Derek, a family member of one of the NJSP students she met, who had been diagnosed with ADD and bipolar disorder. When Derek was 16, he had an outburst in class, but instead of being referred for counseling, a police officer escorted him out of school in handcuffs.

“Instead of understanding the circumstances of the student and why their behavior is disruptive, [schools] have become accustomed to simply expelling or suspending the ‘bad student,’” said Bogert.

A One-Way Passage

While positive outcomes from these zero-tolerance policies are hard to discern, one result is clear: when youths, especially those at risk, are pushed out of school, they are more likely to become involved in criminal activity. A 2014 study published in The Journal of Youth and Adolescence showed that students are almost twice as likely to be arrested on days they are suspended from school. From there, research shows, the problem can easily snowball.

“Students who have been suspended are three times more likely to drop out by the 10th grade than students who have never been suspended,” according to Donna Lieberman of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Testifying in 2008 before the New York City Council Committees on Education and Civil Rights Regarding the Impact of Suspensions on Students’ Education Rights, Lieberman noted, “Dropping out, in turn, triples the likelihood that a person will be incarcerated later in life. In fact, in 1997, 68 percent of state prison inmates were school dropouts.”

There is often little opportunity for incarcerated high school dropouts to earn more than a GED. Many correctional facilities don’t offer college-level courses for inmates. And for returning citizens hoping to further their education upon release, it can be difficult to receive a private student loan.

When you add in the fact that it’s sometimes legal for employers to discriminate against the formerly incarcerated—jobs in education, health care, law enforcement, and the military are generally off-limits for those who have served time, said seniors Alyssa Behr and Steffi Groezinger at the forum—there is little room for the formerly incarcerated to find work in today’s competitive job market.

“Regardless of the length of your sentence or the severity of your crime, what we can all acknowledge is that opportunity is almost absent,” said Groezinger. “So after [someone’s] sentence is completed, they are sentenced to unemployment.”

A 2015 survey by the Ella Baker Center for Human Rights found that 67 percent of respondents were unemployed or underemployed five years after being released from prison. And 79 percent of those surveyed were either ineligible or denied housing. For many of the formerly imprisoned, returning to the streets often seems the only option.

A Costly Cycle

Given these obstacles, it’s perhaps not surprising that two of three formerly incarcerated people end up back in prison within three years of release.

Given these obstacles, it’s perhaps not surprising that two of three formerly incarcerated people end up back in prison within three years of release.

Recidivism’s impact reaches far beyond the prisoner: The 2.7 million children in this country who have an incarcerated parent are more likely to perform poorly in school, exhibit behavioral or mental health issues, and deal with financial, emotional, and familial instability. They are also more than twice as likely to commit delinquent acts. Across the board, ethnic minorities are at greater risk.

“Black youths in New Jersey are 26.2 times more likely to be incarcerated than white youths,” said Bogert. “This proves that not only are we ignoring the problem of at-risk youths being funneled into the school-to-prison pipeline but that it has also become an issue of systemic racism.”

It’s a problem that affects everyone, even those with no direct connection to someone behind bars. In New Jersey, for example, it costs $200,000 a year to incarcerate a youth. The state spends more than $63 million a year on its young inmates, “with only a small fraction of that budget going to community programs to help those youths,” said Bogert. “As a result of lack of funding for rehabilitative programs, there’s an 80 percent recidivism rate for youths in New Jersey.”

Reversing The Flow

The Monmouth students and their NJSP counterparts argued that resources pertaining to education need to be improved, not only during and directly after incarceration but, most importantly, before conviction or arrest, when children are still in school. This, they argued, can be done by ensuring that public schools receive a larger portion of state budgets. That would enable schools to provide better resources for students with disabilities, as well as to support more extracurricular programs in poorly funded districts.

The students also urged the creation of more community-based programs for youths to participate in. One successful example they pointed to is Monmouth’s partnership with the Asbury Park High School Debate Team. For eight years, Monmouth University’s debate team has visited Asbury Park High School not only to coach the students but also to act as mentors and increase the high schoolers’ academic and social learning. “The graduation rate for Asbury Park High School is 66 percent, but the debaters for the past eight years have a 100 percent graduation rate,” said senior Elizabeth Carmines. “Studies show that not only do programs implement a sense of belonging for students and provide social support that [students might] not be getting at home, but students who participate in extracurricular programs also have increased attendance at school, better reading comprehension, and [fewer] disciplinary referrals.”

Both the Monmouth students and their NJSP counterparts also agreed that increasing educational opportunities, including the opportunity to earn advanced degrees, and providing mental health resources for convicts are essential steps for helping them successfully reintegrate into society upon release.

“Part of what the class is doing is also trying to create a space for an educational intervention inside this one particular facility,” said Assistant Professor Johanna Foster, who co-taught the two-semester course with Professor Eleanor Novek. “[NJSP] is a facility that has no access at the moment to higher education, and many of these men are serving extremely long sentences—but the majority of [them] will be released someday.”

Novek echoed that sentiment. “I think people don’t realize incarcerated people are coming back when they’ve served their sentences. And so, what we should want is a system that prepares them to live safely back in their communities, employed legally—which is not a system that we currently have.”

Along those lines, the students stressed during their presentations the importance of eliminating the stigma society often attaches to the formerly incarcerated. That, they argued, would make it easier for them to secure jobs and break the cycle of recidivism.

“Take a moment to think about the worst mistake you ever made in your entire life,” senior Paul Matt said to the audience that day. “Then think about your character and people’s perception of you—[if] that’s how they viewed you for the rest of your life, how would that make you feel?

“The sole purpose of prison should not be to punish, but rather to educate the individuals and show them how they can change their behavior to become productive members of society. Yes, these people committed crimes—but they’re more than their worst mistake.”