By Madison Hanrahan and Emily O’Sullivan

On Friday, March 26, the Monmouth University Institute for Global Understanding (IGU) hosted faculty panels discussing human rights and the environment as part of its biennial symposium. Dr. Catherine Duckett, Associate Dean of the School of Science, moderated a panel featuring Dr. Melissa Alvaré, Dr. Kathleen Grant, Dr. Eric Fesselmeyer, and Dr. Abha Sood. Tony MacDonald, Esq., Director of the Urban Coast Institute, moderated a panel featuring Dr. John Comiskey, Dr. Tom Herrington, and Dr. Robin Mama. The presenters covered a wide variety of informative and engaging topics, ranging from climate gentrification to sustainable development goals.

Dr. Alvaré, a Lecturer in the Department of Political Science and Sociology, was the first panelist of the afternoon. She discussed how sea level rise brought on by climate change has led to challenges for coastal communities, such as flooding. As a result, wealthier coastal communities relocate inland to escape the flooding into low-income and minority communities. This process is known as climate change gentrification. As it is impossible for everyone to move inland, one proposed method to alleviate the risk of flooding in coastal areas is to create green infrastructure such as wetlands and rain gardens to hold stormwater. Dr. Alvaré explained that utilizing green infrastructure in areas prone to flooding can actually cause more gentrification in these areas because this infrastructure, which contributes to the utilities and aesthetics of an area, raises property values, further gentrifying the area and displacing existing communities from their homes. Some examples of cities that are currently affected by climate change gentrification include Southbridge in Wilmington, Delaware; Philadelphia; and Boston. Dr. Alvaré proposed a variety of ways to prevent climate change gentrification, such as utilizing organizations focused on environmental resilience, sustainability, and clean energy initiatives; enforcing rent control and tax freezes; preserving and building affordable housing; and most importantly, organizing within local communities to address gentrification.

Next, Dr. Kathleen Grant, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Educational Counseling, gave a presentation on the link between advocacy for climate change and social justice. She explained white people’s domination of resources and belief that the Earth itself is a resource to be extracted, utilized, sold, and discarded. She compared this view to how groups treat people of color. Dr. Grant provided an example of this issue with a description of the Flint, Michigan water crisis and the construction of pipelines through Indigenous communities. Both examples show how society has neglected to fund and invest in basic life-sustaining infrastructure in many communities of color. This lack of basic human rights toward people of color is evident throughout the United States; from the lead water crisis in Newark, New Jersey to the higher frequency of flooding and natural disasters in low-income communities, and to the industrial and waste sites that are primarily located in poorer neighborhoods. Dr. Grant explained that dominant groups typically have more political and economic power, and since older white males are the dominant demographic in positions of authority in the United States, they protect themselves against these harms, which leads to institutional racism.

Dr. Eric Fesselmeyer, an Associate Professor of Economics, followed Dr. Grant, and presented his work on whether heat affects certain populations disproportionately. His theory is that people trade environmental quality for lower housing costs, which puts many people of color in neighborhoods with more concrete and less nature, thereby increasing the temperature in those communities. Using the 2000 and 2010 U.S. Census data, Dr. Fesselmeyer provided multiple maps and graphs outlining the connection between higher temperatures and factors that define lower-income neighborhoods. He concluded his presentation with substantial evidence that shows a connection between race/origin, rent, income, and college education.

The last speaker on the first Monmouth faculty panel, Dr. Abha Sood, who is a Lecturer in the Department of English, gave her presentation on the displaced community of the Isle de Jean Charles. This island used to be part of the marshes of southern Louisiana, but due to sea level rise and the effects of drilling and infrastructure along the Mississippi River, it is now no more than 320 square acres. The inhabitants were primarily Native Americans who integrated with a small French community. According to Dr. Sood, “Since the inhabitants are a mix of Indian and French Acadians, the government did not recognize them as Native Americans,” which led to the loss of the state government’s financial assistance. In the 1900s, communities along the Mississippi River began to flood, so engineers installed infrastructure such as dams, locks, levees, and floodwalls to protect them. As a result, however, the flow of freshwater and rich sediment that traveled down the Mississippi River to the marshes where the Isle de Jean Charles is located was interrupted which turned the marshes into saltwater and prevented crop cultivation. In 1950, oil companies appeared around the marshes and destroyed the land in search of oil. Additionally, multiple hurricanes in Louisiana further damaged the region, leaving the marshes unrepaired. Due to the Isle de Jean Charles’ poor condition, almost all the residents of the island have left. Louisiana is more focused on the residents who still reside on the island rather than on the tribe. This case study of the Isle de Jean Charles seems to parallel the tribe of Kivalina, Alaska, as both struggled to secure the government’s assistance. As Chief Naquin stated, “The plan is no longer meeting the goals and objectives set out by the residents and IDIC tribe.” The Isle de Jean Charles is just one example of many that show how detrimental climate change can be, especially when multiple parties disregard human involvement’s consequences on the surrounding environment.

Leading off the second Monmouth faculty panel, Dr. John Comiskey, an Assistant Professor in the Department of Criminal Justice, presented a talk titled “Climate Insecurity: An Anthropocene Security Approach to a Sustainable Global Future.” A professor in the Criminal Justice Department, Dr. Comiskey offered a perspective that linked climate inaction to “systemic security risks,” explaining that environmental degradation “undermines our security ecosystems.” Citing Hurricane Katrina as an example, Dr. Comiskey illustrated that natural disasters pose as significant a threat to the nation’s security. Accordingly, the U.S. Department of Homeland Security must “securitize” climate change and consider it of the highest priority. In doing so, the U.S. could achieve climate security, a term Dr. Comiskey defines as the “sustained implementation of prevention, mitigation, and resilience measures necessary to permit the responsible management of climate change risks.”

Dr. Comiskey constructed climate models in which he created several scenarios based on the climate change realities experienced today. He provided attendees with the long-term consequences of such models, which include but are not limited to hospitals stretched beyond capacity; food and water shortages, instigating looting and violence; soaring unemployment; and a nationwide increase in post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), depression and anxiety. Since the United States’ current policies are insufficient to prevent these outcomes, Dr. Comiskey underscored the urgency of bringing the climate crisis to the forefront of security discussions.

Following Dr. Comiskey, Dr. Tom Herrington, the Associate Director of the Urban Coast Institute (UCI), shared his research titled “Climate Change-driven Coastal Migration: State of Our Knowledge and Required Research Questions that Need to Be Answered.” Dr. Herrington began by identifying coastal populations as the most vulnerable to climate change due to sea level rise. Indeed, it is estimated that, by 2100, 13.1 million people in the United States “may be displaced from the coast due to up to six feet of sea level rise.”

With this in mind, Dr. Herrington asked three core questions: Where will this population relocate to, when will the relocation process begin, and what resources are necessary to prepare? First, he found that people will likely move to an area in close proximity to their original home given relocation’s difficulty. Similarly, he concluded that there is a class component for internal migration: those who come from well-resourced communities have an advantage over those from under-resourced neighborhoods. “Where we have highly resourced or privileged populations, they have a lot of capacity to move or to affect their own outcomes whereas, where we have marginalized, under-resourced communities, they are vulnerable and left with few options,” Dr. Herrington explained, echoing Dr. Grant’s presentation. Furthermore, there is minimal data on the whereabouts of those whom natural disasters have displaced. For example, little is known about what happened to the people who Hurricane Katrina devastated, underscoring the need for further research in this area. Thus, Dr. Herrington encouraged increased research on the matter and emphasized the value of learning from past experiences.

Finally, Dr. Robin Mama, the Dean of the School of Social Work, offered a perspective from her field through her work titled “Sustainable Development Goals: Action Comes Alive!” As an International Federation of Social Workers (IFSW) Representative to the United Nations, Dr. Mama discussed the IFSW’s efforts toward sustainable development. The IFSW represents over half a million social workers spanning 141 countries, and the federation possesses special consultative status with the UN. According to Dr. Mama, the IFSW’s focus as an international organization is to “promote social work to achieve social development, to advocate for social justice globally, and to facilitate international cooperation.” As a representative, Dr. Mama advocates for the social work profession and assists the UN in attaining its Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), explaining that social workers are critical components of the latter due to their holistic, interdisciplinary skill sets. For example, social workers are always present in natural disasters and conversant in the discipline of disaster mental health. Therefore, it is clear that social workers are essential combatants in the war against the climate crisis.

To view the recording of the faculty panels, enter the following passcode: @?N0$sY

On March 16, 2021, the Social Work Society at Monmouth University participated in the 37th Annual Social Work Day at the United Nations (UN). This year, the group explored the new world of the COVID-19 pandemic, shining a light on social workers collaborating across borders to discuss education during this time. The event featured several discussion topics, such as online learning and field placements, self-care and socialization, and decolonizing the social work profession. In addition, the discussants addressed how social workers have prepared to work internationally because of the pandemic.

On March 16, 2021, the Social Work Society at Monmouth University participated in the 37th Annual Social Work Day at the United Nations (UN). This year, the group explored the new world of the COVID-19 pandemic, shining a light on social workers collaborating across borders to discuss education during this time. The event featured several discussion topics, such as online learning and field placements, self-care and socialization, and decolonizing the social work profession. In addition, the discussants addressed how social workers have prepared to work internationally because of the pandemic. On March 25, 2021, Monmouth University’s Institute for Global Understanding (IGU) launched its three-day biennial symposium, inviting attendees from around the world to join experts in exploring a central theme: human rights and the environment. Though the IGU had orchestrated several symposia during its initial period of existence, this event marked the relaunched IGU’s first major event since the institute’s hiatus from 2015-2020. Soon after Prof. Randall Abate was appointed Director of the relaunched IGU in March 2020, Abate and his colleagues on the IGU Faculty Advisory Council devoted nearly a year to prepare for the forum, enlisting the help of multiple student assistants and interns along the way. Though the COVID-19 pandemic’s realities forced the symposium to pivot from its usual in-person format, the use of an online platform made for a truly global experience, connecting speakers and participants from across the globe and allowing the IGU to exert its greatest possible impact in its first year back on campus.

On March 25, 2021, Monmouth University’s Institute for Global Understanding (IGU) launched its three-day biennial symposium, inviting attendees from around the world to join experts in exploring a central theme: human rights and the environment. Though the IGU had orchestrated several symposia during its initial period of existence, this event marked the relaunched IGU’s first major event since the institute’s hiatus from 2015-2020. Soon after Prof. Randall Abate was appointed Director of the relaunched IGU in March 2020, Abate and his colleagues on the IGU Faculty Advisory Council devoted nearly a year to prepare for the forum, enlisting the help of multiple student assistants and interns along the way. Though the COVID-19 pandemic’s realities forced the symposium to pivot from its usual in-person format, the use of an online platform made for a truly global experience, connecting speakers and participants from across the globe and allowing the IGU to exert its greatest possible impact in its first year back on campus. addressed the virtual crowd. Born in Long Branch, Congressman Pallone has firsthand experience with the Monmouth community. He has served in the U.S. House of Representatives since 1988 and currently represents New Jersey’s 6th congressional district, a position in which he fights for many issues that are integral to the IGU’s mission. Specifically, he is a fierce environmental justice advocate, combating the climate crisis in his role as the Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and working to maintain the ecological integrity of coastal New Jersey communities.

addressed the virtual crowd. Born in Long Branch, Congressman Pallone has firsthand experience with the Monmouth community. He has served in the U.S. House of Representatives since 1988 and currently represents New Jersey’s 6th congressional district, a position in which he fights for many issues that are integral to the IGU’s mission. Specifically, he is a fierce environmental justice advocate, combating the climate crisis in his role as the Chairman of the House Energy and Commerce Committee and working to maintain the ecological integrity of coastal New Jersey communities. In relation to this passion, he happily reported that the United States has become “re-engaged” in the battle against climate change, with President Biden rejoining the Paris Agreement during his first days in office and reinstating important relationships with international allies. Given the urgency regarding climate action, such measures are paramount. Congressman Pallone remarked that New Jersey residents in particular experience the consequences of inaction, hearkening back to the devastation of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and the years it took to rebuild what had been destroyed. With this in mind, he stressed the importance of service at both the local and global levels, and he praised the university for its commitment to “international affairs and global understanding” and to “the local community and so many things involving the Jersey Shore.” The IGU similarly values local-global connections, and it strives to promote an environmentally just future alongside key leaders in the movement like Congressman Pallone.

In relation to this passion, he happily reported that the United States has become “re-engaged” in the battle against climate change, with President Biden rejoining the Paris Agreement during his first days in office and reinstating important relationships with international allies. Given the urgency regarding climate action, such measures are paramount. Congressman Pallone remarked that New Jersey residents in particular experience the consequences of inaction, hearkening back to the devastation of Hurricane Sandy in 2012 and the years it took to rebuild what had been destroyed. With this in mind, he stressed the importance of service at both the local and global levels, and he praised the university for its commitment to “international affairs and global understanding” and to “the local community and so many things involving the Jersey Shore.” The IGU similarly values local-global connections, and it strives to promote an environmentally just future alongside key leaders in the movement like Congressman Pallone. principle into the institute’s mission. Through her current posts as Monmouth’s Interim Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, Dr. Datta works toward this vision on a university-wide scale. Speaking after Congressman Pallone, she provided a bit of insight into the IGU’s history, explaining that “a small group of faculty and staff getting together in the student center in June of 2001 and just wondering what we could do to promote more global and cultural literacy on this campus” spearheaded the IGU’s creation. Guided by Margaret Mead’s philosophy, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has,” the IGU was born. Functioning as a space of faculty and student engagement throughout its 20-year history, the IGU has long envisioned a world that understands the connection between human rights and the environment as significant to every living being, and the re-launched IGU now hopes to build on Dr. Datta and her colleagues’ legacy.

principle into the institute’s mission. Through her current posts as Monmouth’s Interim Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs, Dr. Datta works toward this vision on a university-wide scale. Speaking after Congressman Pallone, she provided a bit of insight into the IGU’s history, explaining that “a small group of faculty and staff getting together in the student center in June of 2001 and just wondering what we could do to promote more global and cultural literacy on this campus” spearheaded the IGU’s creation. Guided by Margaret Mead’s philosophy, “Never doubt that a small group of thoughtful, committed citizens can change the world; indeed, it’s the only thing that ever has,” the IGU was born. Functioning as a space of faculty and student engagement throughout its 20-year history, the IGU has long envisioned a world that understands the connection between human rights and the environment as significant to every living being, and the re-launched IGU now hopes to build on Dr. Datta and her colleagues’ legacy. Professor Burkett began her talk by establishing the linkages among racism, racial hierarchy, environmental degradation, and the law, deeming contemporary climate change “the climax of centuries of wrong relationships with our natural environment.” She then proceeded to discuss climate migration within our constructed geopolitical landscape, explaining that man-made borders exacerbate the conditions of climate-driven movement and perpetuate “racialized exclusion.” Before diving further into her discussion, she defined common terms in the climate mobility lexicon, differentiating between climate displacement and climate migration on the basis that the latter implies a degree of voluntary movement while the former results from short-term force. On a similar note, a key understanding of climate migration is that the most vulnerable — the poor — often lack the resources to emigrate from their established communities, creating a problem of “trapped populations.” Moreover, climate migrants cannot turn to any legitimate source of recourse, for no single governance entity is required to respond to their troubles. Consequently, Professor Burkett moved onto an analysis of reparations, citing various scholars who hold that countries that have historically contributed to the climate change crisis should assume responsibility for mitigating the challenges that accompany today’s climate migration. She also noted that the most substantive reparation is one committed to the principle of “non-repetition,” guaranteeing that future communities will not have to withstand the past’s ills.

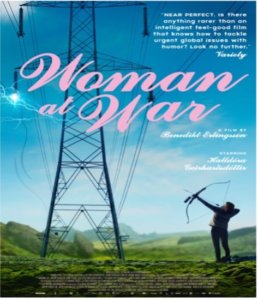

Professor Burkett began her talk by establishing the linkages among racism, racial hierarchy, environmental degradation, and the law, deeming contemporary climate change “the climax of centuries of wrong relationships with our natural environment.” She then proceeded to discuss climate migration within our constructed geopolitical landscape, explaining that man-made borders exacerbate the conditions of climate-driven movement and perpetuate “racialized exclusion.” Before diving further into her discussion, she defined common terms in the climate mobility lexicon, differentiating between climate displacement and climate migration on the basis that the latter implies a degree of voluntary movement while the former results from short-term force. On a similar note, a key understanding of climate migration is that the most vulnerable — the poor — often lack the resources to emigrate from their established communities, creating a problem of “trapped populations.” Moreover, climate migrants cannot turn to any legitimate source of recourse, for no single governance entity is required to respond to their troubles. Consequently, Professor Burkett moved onto an analysis of reparations, citing various scholars who hold that countries that have historically contributed to the climate change crisis should assume responsibility for mitigating the challenges that accompany today’s climate migration. She also noted that the most substantive reparation is one committed to the principle of “non-repetition,” guaranteeing that future communities will not have to withstand the past’s ills. On Thursday, April 15, the World Cinema Series rounded out an enlightening year of film analysis with Benedikt Erlingsson’s Woman at War. The capstone of the 2020-2021 theme, “A Delicate Balance: Global Communities and the Natural Environment,” the 2018 release invites viewers to grapple with one of the most pressing issues of our time: human-induced climate change. Set as a battle between Halla, a middle-aged environmental activist devoted to ecological integrity, and the Icelandic government’s plans for a multinational corporation’s construction of an aluminum plant, the film communicates a poignant message: this generation is the last capable of coming to the Earth’s defense in the long-running war against it, and there is simply not any time left to waste.

On Thursday, April 15, the World Cinema Series rounded out an enlightening year of film analysis with Benedikt Erlingsson’s Woman at War. The capstone of the 2020-2021 theme, “A Delicate Balance: Global Communities and the Natural Environment,” the 2018 release invites viewers to grapple with one of the most pressing issues of our time: human-induced climate change. Set as a battle between Halla, a middle-aged environmental activist devoted to ecological integrity, and the Icelandic government’s plans for a multinational corporation’s construction of an aluminum plant, the film communicates a poignant message: this generation is the last capable of coming to the Earth’s defense in the long-running war against it, and there is simply not any time left to waste. f climate change, Dr. Duckett finds great reward in helping her students “find their activist voice.” She approached the film with an understanding that “climate change in the United States is often viewed from a lens clouded by misinformation… when climate scientists share their knowledge, they’re often labeled as an extremist or as an alarmist when, for the most part, they have been erring on the side of caution and sugarcoating results.” From this perspective, she launched a conversation surrounding a key question at the root of the story’s narrative: how can one distinguish between an activist and an extremist?

f climate change, Dr. Duckett finds great reward in helping her students “find their activist voice.” She approached the film with an understanding that “climate change in the United States is often viewed from a lens clouded by misinformation… when climate scientists share their knowledge, they’re often labeled as an extremist or as an alarmist when, for the most part, they have been erring on the side of caution and sugarcoating results.” From this perspective, she launched a conversation surrounding a key question at the root of the story’s narrative: how can one distinguish between an activist and an extremist? and she spent two years serving in the Peace Corps before earning her Ph.D. at Michigan State University and arriving at Monmouth University in 2002. A specialist in family sociology, she pointed out another conflict at the heart of the film: can Halla identify as both a “good mother” and a fearless activist? To Dr. Mezey, this issue represents a similar false dichotomy, especially given that the definition of a “good mother” varies widely from culture to culture. In Woman at War, Halla’s bold stance against the climate injustice before her reflects her take on both motherhood and activism: “It is our inalienable right to protect future generations, and our children and our grandchildren will have no chance unless we act now.”

and she spent two years serving in the Peace Corps before earning her Ph.D. at Michigan State University and arriving at Monmouth University in 2002. A specialist in family sociology, she pointed out another conflict at the heart of the film: can Halla identify as both a “good mother” and a fearless activist? To Dr. Mezey, this issue represents a similar false dichotomy, especially given that the definition of a “good mother” varies widely from culture to culture. In Woman at War, Halla’s bold stance against the climate injustice before her reflects her take on both motherhood and activism: “It is our inalienable right to protect future generations, and our children and our grandchildren will have no chance unless we act now.” Professor Maiya Furgason, an instructor in the Leon Hess Business School with over 35 years of wealth management experience and whose travels span 103 countries, offered critical insight about the Icelandic corporate setting. Mainly, she dissected the “major role of industrial sabotage” against ecological initiatives that has left world citizens without “much time to rescue our environment.” Though the aluminum plant only employed a few hundred of Iceland’s 343 million people, it accounted for roughly 23 percent of the country’s GDP, forcing the Icelandic government to juggle between environmental and fiscal interests. Unfortunately, the latter frequently prevail over the former, underscoring the significance of generating discussions like those that have transpired at the World Cinema Series events all year long.

Professor Maiya Furgason, an instructor in the Leon Hess Business School with over 35 years of wealth management experience and whose travels span 103 countries, offered critical insight about the Icelandic corporate setting. Mainly, she dissected the “major role of industrial sabotage” against ecological initiatives that has left world citizens without “much time to rescue our environment.” Though the aluminum plant only employed a few hundred of Iceland’s 343 million people, it accounted for roughly 23 percent of the country’s GDP, forcing the Icelandic government to juggle between environmental and fiscal interests. Unfortunately, the latter frequently prevail over the former, underscoring the significance of generating discussions like those that have transpired at the World Cinema Series events all year long. On Friday, April 8, the Urban Coast Institute (UCI) and the Institute of Global Understanding (IGU) co-hosted a Global Ocean Governance panel focused on the topic of global fisheries governance and social justice. This panel included three speakers: Dr. Erika Techera, a professor of environmental law at the University of Western Australia; Dr. Xiao Recio-Blanco, the director of the Ocean Program at the Environmental Law Institute; and Dr. Yoshitaka Ota, a research assistant professor at the School of Marine & Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington. The panelists discussed issues such as social justice and accountability, the promotion of small-scale fisheries and sustainable fisheries, and the blue economy.

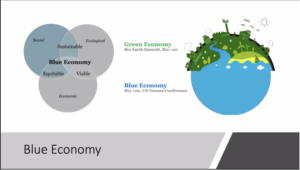

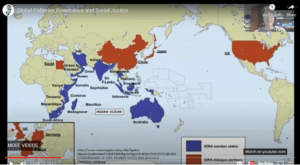

On Friday, April 8, the Urban Coast Institute (UCI) and the Institute of Global Understanding (IGU) co-hosted a Global Ocean Governance panel focused on the topic of global fisheries governance and social justice. This panel included three speakers: Dr. Erika Techera, a professor of environmental law at the University of Western Australia; Dr. Xiao Recio-Blanco, the director of the Ocean Program at the Environmental Law Institute; and Dr. Yoshitaka Ota, a research assistant professor at the School of Marine & Environmental Affairs at the University of Washington. The panelists discussed issues such as social justice and accountability, the promotion of small-scale fisheries and sustainable fisheries, and the blue economy. Dr. Techera’s prerecorded presentation addressed illegal fishing and governance in the Indian Ocean. She emphasized the Indian Ocean’s importance, as it connects multiple regions and countries with vastly different cultures, development, and laws that comprise a diverse and unique realm of fishing governance. Because this region is the fastest growing economy in the world, it is critical that policymakers and researchers examine and improve ocean and fishing regulations. All the countries in this region are highly dependent on the ocean. Dr. Techera noted that ensuring sustainable fishing practices in the Indian Ocean is necessary for the environment and for the region’s future development. In light of the fact that the technology to create sustainable fisheries already exists, there should be no hesitation in adopting the technologies. Dr. Techera explained that two areas of concern for countries surrounding the Indian Ocean and for the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) member states are that the region researchers and states need to improve their understanding and recognition of the region to help these countries achieve their blue economy goals and confirm that sustainable fishing is crucial for this region. The countries bordering the Indian Ocean rely on the ocean for food, for security, and for their peoples’ livelihoods.

Dr. Techera’s prerecorded presentation addressed illegal fishing and governance in the Indian Ocean. She emphasized the Indian Ocean’s importance, as it connects multiple regions and countries with vastly different cultures, development, and laws that comprise a diverse and unique realm of fishing governance. Because this region is the fastest growing economy in the world, it is critical that policymakers and researchers examine and improve ocean and fishing regulations. All the countries in this region are highly dependent on the ocean. Dr. Techera noted that ensuring sustainable fishing practices in the Indian Ocean is necessary for the environment and for the region’s future development. In light of the fact that the technology to create sustainable fisheries already exists, there should be no hesitation in adopting the technologies. Dr. Techera explained that two areas of concern for countries surrounding the Indian Ocean and for the Indian Ocean Rim Association (IORA) member states are that the region researchers and states need to improve their understanding and recognition of the region to help these countries achieve their blue economy goals and confirm that sustainable fishing is crucial for this region. The countries bordering the Indian Ocean rely on the ocean for food, for security, and for their peoples’ livelihoods. process to create effective laws regarding small-scale fisheries due to a general lack of understanding of small-scale fisheries, inadequate organization, a focus on industrial fisheries for additional profit, and policymakers overlooking small-scale fisheries in their agendas. Dr. Recio-Blanco suggested solutions to unregulated small-scale fisheries, among them adopting additional guidelines for small-scale fisheries to follow, using legal language in laws that affect small-scale fisheries, ensuring the writer of these laws understands how small-scale fisheries operate, and encasing the discussion of small-scale fisheries using a human rights lens. With his suggestions, countries can ensure effective and sustainable small-scale fishing for decades to come.

process to create effective laws regarding small-scale fisheries due to a general lack of understanding of small-scale fisheries, inadequate organization, a focus on industrial fisheries for additional profit, and policymakers overlooking small-scale fisheries in their agendas. Dr. Recio-Blanco suggested solutions to unregulated small-scale fisheries, among them adopting additional guidelines for small-scale fisheries to follow, using legal language in laws that affect small-scale fisheries, ensuring the writer of these laws understands how small-scale fisheries operate, and encasing the discussion of small-scale fisheries using a human rights lens. With his suggestions, countries can ensure effective and sustainable small-scale fishing for decades to come.

included undergraduate student and aspiring educator Emma Cooper’s Spanish Ode to Mother Earth — which she wrote for a course with Associate Professor Dr. Alison Maginn in the Department of World Languages and Cultures — and the School of Social Work graduate student Hannah Burke’s “The Embalming Song,” which explores unsustainable modern death practices and her post-mortem plan to honor the Earth. Burke also delivered a presentation on the subject the following day during the Monmouth University Student Panel along with interdisciplinary presentations from four other undergraduate and graduate students. Other contributions include Julia Poaella’s original poetry on social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and fifth grader Jeff Jiju’s recommendations for sustainable living.

included undergraduate student and aspiring educator Emma Cooper’s Spanish Ode to Mother Earth — which she wrote for a course with Associate Professor Dr. Alison Maginn in the Department of World Languages and Cultures — and the School of Social Work graduate student Hannah Burke’s “The Embalming Song,” which explores unsustainable modern death practices and her post-mortem plan to honor the Earth. Burke also delivered a presentation on the subject the following day during the Monmouth University Student Panel along with interdisciplinary presentations from four other undergraduate and graduate students. Other contributions include Julia Poaella’s original poetry on social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic, and fifth grader Jeff Jiju’s recommendations for sustainable living. Throughout the documentary, the village faces a huge obstacle: climate change. The filmmaker, Gina Abatemarco, explores how climate change impacts Kivalina and its community members. The film also delves into the people’s lifestyles, culture, food sources, and views on climate change as well as the government’s role in response to this ongoing threat.

Throughout the documentary, the village faces a huge obstacle: climate change. The filmmaker, Gina Abatemarco, explores how climate change impacts Kivalina and its community members. The film also delves into the people’s lifestyles, culture, food sources, and views on climate change as well as the government’s role in response to this ongoing threat. commentary portion of the event, the audience heard from three speakers: Enoch Adams, a member of Kivalina; Dr. Kelsey Leonard, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo in Ontario and an expert on indigenous legal rights; and Gina Abatemarco, the filmmaker. Mr. Adams described how Kivalina has been moving forward in its evacuation efforts due to climate change. He discussed how the island has built an evacuation road and hosts a new inland school site. Furthermore, he stated that the community is split about the new school, as the majority of the community stayed while some community members decided to live near the new school. He also noted that the community is fond of Abatemarco, the filmmaker, and how she embraced the community.

commentary portion of the event, the audience heard from three speakers: Enoch Adams, a member of Kivalina; Dr. Kelsey Leonard, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo in Ontario and an expert on indigenous legal rights; and Gina Abatemarco, the filmmaker. Mr. Adams described how Kivalina has been moving forward in its evacuation efforts due to climate change. He discussed how the island has built an evacuation road and hosts a new inland school site. Furthermore, he stated that the community is split about the new school, as the majority of the community stayed while some community members decided to live near the new school. He also noted that the community is fond of Abatemarco, the filmmaker, and how she embraced the community. sense of place that Kivalina was experiencing. During her seven-year journey in making the film, she formed deep friendships and connections and, through doing so, gained knowledge about the culture.

sense of place that Kivalina was experiencing. During her seven-year journey in making the film, she formed deep friendships and connections and, through doing so, gained knowledge about the culture. the 2019 film Honeyland. Dr. Thomas Pearson moderated this event with faculty discussants Dr. Pedram Daneshgar and Dr. Mihaela Moscaliuc on March 11 at 7:30 p.m. via Zoom.

the 2019 film Honeyland. Dr. Thomas Pearson moderated this event with faculty discussants Dr. Pedram Daneshgar and Dr. Mihaela Moscaliuc on March 11 at 7:30 p.m. via Zoom. Associate Professor of Biology and recipient of the 2020 Distinguished Teaching Award at Monmouth University, has extensively researched the biology and ecology of the stars of the film: bees. He emphasized that bees work extremely hard to gather nectar and pollen when flowers are in bloom. While consuming some, they ultimately bring back much more to the hive in order to sustain it, especially during the inactive winter months.

Associate Professor of Biology and recipient of the 2020 Distinguished Teaching Award at Monmouth University, has extensively researched the biology and ecology of the stars of the film: bees. He emphasized that bees work extremely hard to gather nectar and pollen when flowers are in bloom. While consuming some, they ultimately bring back much more to the hive in order to sustain it, especially during the inactive winter months. Dr. Mihaela Moscaliuc, Associate Professor of English and the recipient of a Fulbright fellowship to Romania, discussed bees in their ecological symbolism across cultures and recent centuries. She also examined the interaction and structures of labor and care between the characters Hatidze and Hussain. Both of these characters depend on natural resources for survival; however, they represent two different positions on how their dependency works.

Dr. Mihaela Moscaliuc, Associate Professor of English and the recipient of a Fulbright fellowship to Romania, discussed bees in their ecological symbolism across cultures and recent centuries. She also examined the interaction and structures of labor and care between the characters Hatidze and Hussain. Both of these characters depend on natural resources for survival; however, they represent two different positions on how their dependency works. an beings are merely guests to the home that is the Earth. She lives and works with the bees — not as their owner but as a guest in a world where there are sufficient resources for everyone as long as each person learns that there is enough on which to live and enough to sell if one can behave responsibly and honor the resources that others provide.

an beings are merely guests to the home that is the Earth. She lives and works with the bees — not as their owner but as a guest in a world where there are sufficient resources for everyone as long as each person learns that there is enough on which to live and enough to sell if one can behave responsibly and honor the resources that others provide.